Whilst we have known that this insidious problem exists and is ubiquitous, with so many different sources such as research studies, reports’ and the UN’s statistics featuring the scale of the problem, the recent outpouring of personal accounts via the media and the #MeToo movement unleashes in many of us the hurt and pain bottled away from similar experiences in contexts where there were codes of conduct, trust and the expectation of basic human decency.

Men who abuse positions of power to take liberties, abuse trust and feed on vulnerability. They enliven a tacit silent primitive patriarchal norm that they have the right to assert their power over women.

This power imbalance that drives the abuse in male dominated workplaces, deepens as women often go underground with their pain from the violation, fear of the abuser, confusion about what to do and whom to confide in. On the other hand, the abusers set their sights on new targets in cultures where the powerful blatantly look the other way, wipeout voices demanding a hearing and whiteout those pleading for justice.

In the face of the current momentous turning point that recognises the depth and breadth of sexual harassment nationally and globally, how can we strategise for women to be safe in workplaces when such victimisation continues to be rife? This occurs despite sex discrimination legislation, human rights policies and workplace cultures mouthing respect and equality.

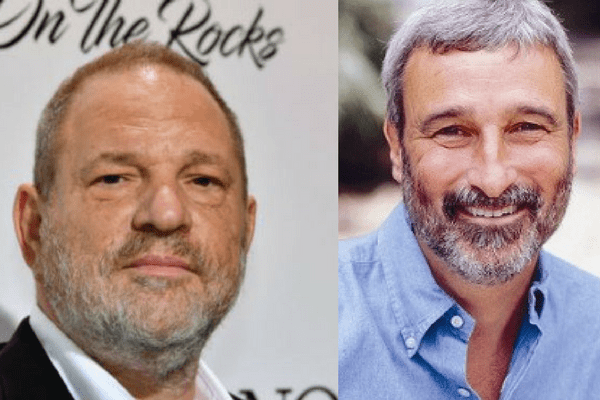

What seems to be evident from the recent unfolding of sexual harassment allegations against Hollywood producer, Harvey Weinstein and Australian television presenter, Don Burke is that it needs someone who is independent, trusted, experienced and competent to conduct the investigation and who cannot be influenced by the alleged abuser.

Beyond this, what is key is that investigators need to be backed by partnering organisations that support and give them platforms to bring attention to the issues raised by victims of the abuse.

Journalists, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey who investigated and reported harassment allegations against Weinstein had the support of The New York Times. Journalist Tracey Spicer, a Fairfax Media columnist, brought on board the ABC’s investigative unit and Fairfax Media to join her. These experienced and trusted investigative journalists did the digging, asked the questions, analysed the responses, and saw the patterns in what emerged that consolidated the allegations.

The media organisations backing them, provided the resources needed to substantiate stories and gave them platforms to name the perpetrators and their alleged abuse. Not only have more women come forward to share their stories against named abusers, but this has catalysed an avalanche of sharing of sexual harassment experiences in different sectors and contexts.

Can this approach be replicated further to eradicate sexual harassment in workplaces? It would require independent experienced trusted investigative journalists who have the backing of media firms to report and name the perpetrators after complaints are substantiated.

A sector-by-sector sexual harassment investigation might bring to the fore entrenched abusers of power. It could lead to comparative findings across sectors to shape policy, instil resounding themes of accountability of all stakeholders and ultimately tally Australia’s progress in eradicating sexual discrimination.

Such an undertaking, in requiring a heavy investment of time and resources, would be challenging for journalists and media companies in the current 24 hour news cycle and commercial pressures.

Alternatively, an independent statutory organisation reporting to Federal Parliament would be ideal, as it would have the power to observe compliance to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 and enable policy development, as well as education and public awareness.

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) is well placed to undertake this task as it has already been conducting national telephone surveys since 2003 on the prevalence, nature and reporting of sexual harassment in Australian workplaces.

In 2003 the AHRC’s interviews with 1,006 individuals between 18 and 64 years of age revealed that sexual harassment was widespread in Australian workplaces and only a small proportion of individuals who had been sexually harassed had made a formal report or complaint about that harassment.

AHRC’s 2008 national telephone survey involving interviews with 2,005 individuals found that sexual harassment continued to be a problem in Australian workplaces, despite some improvements since 2003, but that victims infrequently reported sexual harassment to employers or other bodies.

In 2012, AHRC engaged Roy Morgan Research to conduct its third sexual harassment national telephone survey which involved interviews with 2,002 individuals aged 15 years and over, and an additional 1,000 members of the Australian Defence Force (ADF), as part of phase two of the Review into the Treatment of Women in the Australian Defence Force Academy and Australian Defence Force.

This allowed for comparisons to be made between sexual harassment in targeted workplaces and the ADF workplace. The review found that one in four women in the ADF had experienced sexual harassment in the past five years – a similar rate to the wider community, and that complaints had often not been lodged because service members feared reprisals.

The Review suggested 21 recommendations to support ADF to introduce cultural change. This has had an impact with Australian Federal Police records showing that only three sexual assault charges were laid at the Australian Defence Force Academy between July 1, 2015 and July 31, 2017.

All in all, AHRC’s national scale investigative initiatives and its fine-tuning of the direction, scope and impact of its sexual harassment investigation are to be commended. A critical element missing from AHRC’s investigations, however, is the naming of perpetrators and their actions.

AHRC’s research continues to confirm that reporting sexual harassment is avoided by victims due to fears about the negative consequences of doing so. This includes, as AHRC Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins has stated, “being labelled a trouble maker, being ostracised, victimised or ignored by colleagues”.

The impact of naming perpetrators and their actions, as evident in the recent wave of allegations by women has, in an incredibly short time span, substantiated the extent of abuse by the perpetrator and empowered more women to speak out about their experiences by the same abuser. It has also empowered women to share other stories of abuse, naming different abusers.

Naming the perpetrators and their actions publicly has singularly broken the glass ceiling of silence and tolerance of sexual harassment norms, and as such must be integrated into any comprehensive approach taken to eradicate sexual harassment in workplaces.

The following aspects are necessary:

- strategies to address sexual harassment in workplaces are forceful and not passive

initial sexual harassment investigation deepens in scope and depth when victims reveal perpetrators so that the extent of abuse can be uncovered - perpetrators are publicly named and brought to justice

outcomes of the investigation are public so that others see that offences are being dealt with seriously and justice is being served - company boards are held accountable for not addressing incidents of sexual harassment

- victims have supportive workplace frameworks established to support and assist them reveal their stories and cope as they face pressures of additional investigative requirements related to the incident(s)

- witnesses and whistleblowers who give evidence are supported in workplaces

any repercussion against victims, witnesses and whistleblowers is monitored and workplaces are required to redress this comprehensively - sexual harassment workplace policies state that perpetrators of sexual harassment will be named publicly and brought to justice

Instilling a new norm of zero tolerance of any level of sexism in Australian workplaces is not impossible but it requires power and support. A statutory body such as the AHRC is a leading voice understanding the status of sexual discrimination in workplaces and the factors perpetuating it.

If it requires further power to bring about change, then it can be assured that there is a high level of public support for zero tolerance of any level of sexism to become a firm norm in Australia.