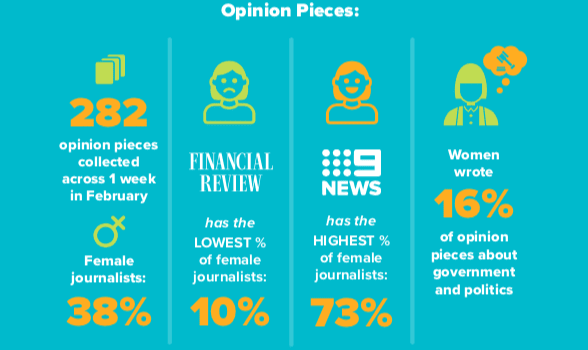

“I don’t think I had really understood just how rarely women write about politics in their opinion pieces,” Price told Women’s Agenda. “It’s surprising that the gender patterns are still so prevalent in 2019. That’s a worry and it’s made me examine my own practices.”

The Women’s Leadership Institute Australia 2019 Women for Media Report: ‘You can’t be what you can’t see’, was undertaken by researchers from the University of Technology Sydney, supported by the Trawalla Foundation, and took a snapshot of Australia’s most influential news sites on four consecutive Thursdays in October 2018.

It is just a glimpse, “a very small sample of a bigger picture” but it gives an idea of what’s going on in Australian news.

The 15 news sites included The Australian, The Guardian, ABC, The Herald-Sun, The Daily Mail, Yahoo7, 9News, BuzzFeed, The West-Australian, The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald.

The results show that women are, largely, missing. We might make up 50.7% of the population but that is not reflected in the media, particularly not in opinion pieces and columns, and especially not in politics and business.

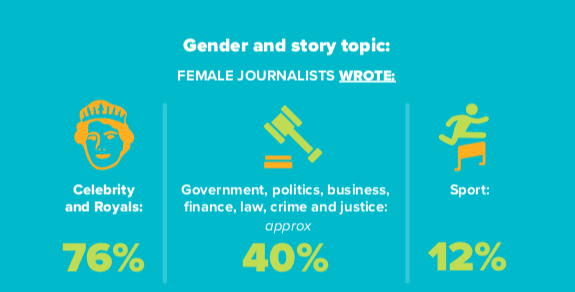

“We read stories about men, by men. Our snapshot showed men were quoted far more often than women and that the stories by male journalists were positioned slightly more often in the top spots on the home pages of these websites. Women write about royals and men write about political leaders. Men write about sport, women write about media, the arts and entertainment.”

Across the data set from all of the sites analysed, the by-lines approached an equal gender split.

“I was happy that about half of the bylines for the top stories was reaching parity because when I started working in 1982 that certainly wasn’t the case,” Price says. “But it disturbs me that women write about royalty and celebrities and not politics. What disturbs me more as a teacher is that it’s very rare for female students to say they want to write about politics.”

The report shows the average representation of female sources was just over one-third. Only the stories on one news site quoted more women than men; and that was Buzzfeed Australia.

Of the rest, the next best was 9News with women representing 45% of the sources quoted but at the other end sits the Australian Financial Review, where women made up only 14% of sources.

“As those sources, we are missing from news stories and from feature stories, we are missing from photos both as photographers and as subjects; and we are missing in that very influential place in the Australian media landscape, our voices are missing from opinion pieces and columns.”

The question of why this matters, is easily answered: We can’t be what we can’t see.

“Research on role models tells us that we need role models because they represent the possible, they are inspirational, they tell us how to behave. And of course, it’s not just good for women to have women role models, it’s also good for boys and men.”

If men are framed as experts in the media, it becomes accepted that men are experts. Conversely, if women are absent and not framed as experts that perception can quickly become the reality.

Increasing the representation of women as sources is a change Price says requires journalists and editors to actively seek out diversity in the sources they quote and publish, but it also requires women to say yes when they’re asked to comment.

“I have never never never had a man say to me ‘I’m not the best person’ when I’ve asked to interview them. Sometimes they say ‘I’m too busy’ but never ‘Ask someone else’,” Price says. “But women, smart and capable women, often say to me ‘I’m not the best person on this subject have you thought of x, y or z?’ when I ask them to be in a story.”

Coaching women into their ability to be a source is time consuming but an absolutely necessary endeavour. “I do think it’s part of my responsibility as a journalist,” Price says.

Ensuring more women are comfortable being quoted and regarded as experts is a quantum cultural shift that won’t happen overnight.

Both the Australian Financial Review and The Australian had close to gender parity in the representation of male and female journalists on the top five new stories. But 90% of the opinion pieces in the data set from the Fin were written by men and 84% of the opinion pieces in The Australian were authored by males.

These figures indicate that the institutional work environments need to be considered: perhaps it is more than individual choices made by journalists that creates this disparity.

“Across our entire data set, a higher proportion of opinion pieces on the topics of government and politics and business and finance were written by men compared to news stories on these topics. So, you could say that while women were trusted to report the information, they were not trusted to interpret it.”

Price admits that structural factors and individual choices need to be scrutinised.

“The trouble is,” Jenna Price reflects in the realm of opinion writing. “If I don’t write about domestic violence in op-ed pages I doubt men would. The reality is very few men write about domestic violence. I can’t remember the last time a man wrote about childcare.”

If more journalists and editors take this research on board and implement change as a result Price will be satisfied.

“It’s great to do academic research so we have this information, but we also need to think about its impact on people. I hope female columnists who read this start writing about franking credits and negative gearing.”