Juggling complex care needs is something that 2.65 million Australians are contending with every day.

Carers, on average, spend about 36 hours a week caring, but this number can jump up to as much as 105 hours a week in many cases, according to Annabel Reid, CEO of Carers Australia.

Speaking on a recent panel about care inclusivity in the workplace, Reid said that when we really think about these statistics, it’s clear that caring is “almost like a full-time, or two full-time jobs, on top of paid employment, which obviously makes it really challenging”.

For employers looking to make their workplaces more inclusive to caregivers, Reid points to something she says is spoken to a lot–flexibility– which can help accommodate any outside responsibilities an employer may have, such as medical appointments and emergencies.

It’s also about employers being “responsive”, says Reid, as employees with caring responsibilities often “get surprises and interruptions and things come up unexpectedly”.

“So, having an employer that’s able to be responsive and understand that it’s not always planned time away or planned flexibility– things can come up.”

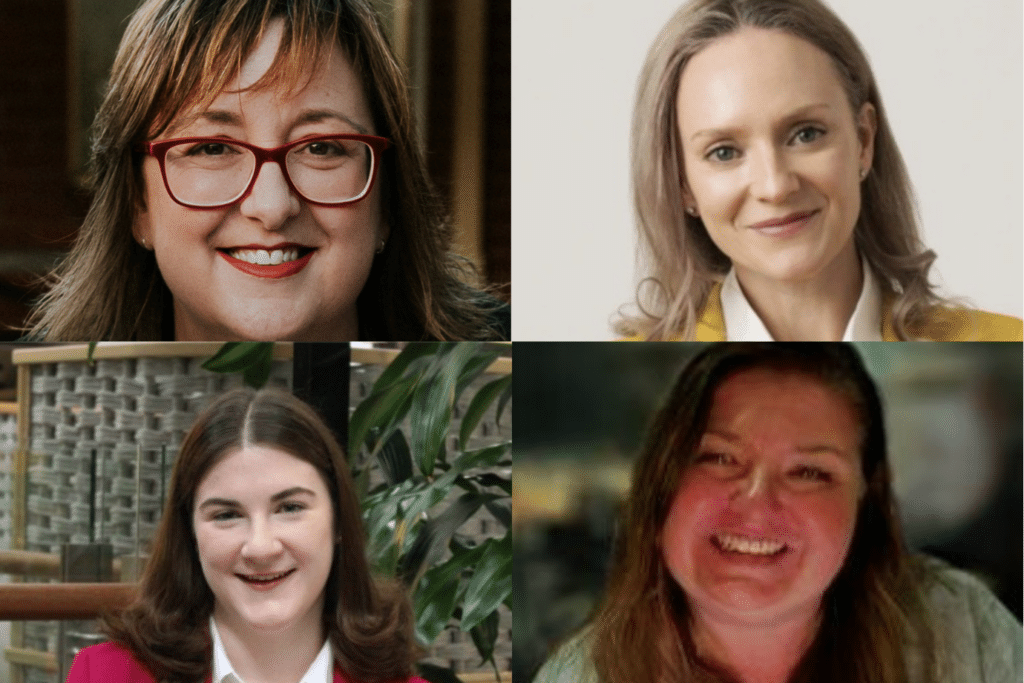

During the webinar, Promoting Carer Inclusivity in the Workplace, Reid was among other powerhouse female advocates in the caregiving space. Delivered by Women’s Agenda in partnership with Carers Australia, the discussion coincided with the newly launched Care Inclusive Workplace Initiative, spearheaded by the Department of Social Services alongside Carers Australia.

This initiative aims to create more inclusive and supportive workplaces for carers who provide unpaid care in the community, and emerged as a result of recommendations from the Australian Government’s Jobs and Skills Summit.

Avoiding caregiving burnout

“Only a carer can truly appreciate the physical, the emotional and the time intensive… toll of being a carer,” Kristine Rawlinson, Project Manager at Neighbourhood Houses Victoria, told the webinar.

“I wish I had known that when I was a health professional and then a policy maker, I think I would have made much better decisions and recommendations that actually affected people’s lives,” added Rawlinson, who has an extensive background as a carer and as a health professional and policymaker in the caring space.

“Even if you’re not in the act of providing physical care for your loved one, you’re always on, you are always on duty.”

“And it’s as an expectation that I don’t actually have anything else going on in my life and that I can drop everything and provide an answer immediately and that I have the capacity to take on more roles,” Rawlinson said.

“So we feel like we’re letting our employer down with feeling like we’re letting our loved ones down. We feel like we’re letting our friends and families down and what we tend to do is we overcompensate. We overwork, and then we eventually burn out. And carers burning out isn’t good for anyone.”

Her advice to employers is to reassure their caregiver employees of their value to the company.

“Carers don’t need to prove anything and be above and beyond what is expected of other employees,” she said.

“We’re loyal, we’re good at multitasking and we also value the opportunity to have time away from our caring role, and something that fulfills our identity beyond that of being a carer.”

Caregiving through different life stages

The face of caregiving is also not a singular type of person.

When picturing caregivers, many people might not think of a young person, and yet, Jacqueline de Mamiel holds that title at only 19-years-old. She’s been navigating the role of carer for her two brothers for a number of years as well as her mum, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016.

“Often when we think of carers, we think of older adults caring for maybe their parents and the older generation, or caring for their own kids, but for me, I really was a child caring for other children,” she says, speaking on the panel. “I quite naturally took on a caring role from a very young age.”

In her daily life, de Mamiel managed her brothers’ medications, managed the health crises that came up– dealing with emergency services when necessary– and said they all “took quite a big toll”.

“Obviously not things that most children experience at such a young age,” she says. “So it’s definitely been a big part of my life growing up and has told me some really valuable skills.”

Diversity, Inclusion and Wellbeing Manager at Hall & Wilcox Antoinette Totta advises employers to have a very compassionate view in regards to what caregiving requires as “it changes through life stages and through ages for everybody”.

“I’ve always taken for granted that I’ve been a carer for most of my life,” Totta shared, noting that she comes from a large family that required her to look after younger relatives.

In addition to that, she lost her father four years ago, after caring for him “in a really immediate capacity” through his dementia.

“And then now, I have mum, so I’ve had to relocate– have moved back in with mum informally, ” she said, adding that these experiences have all contributed to her understanding of the work of caregiving.

“I’ve been able to bring that lens and that perspective into the workplace.”

“Everyone will be a carer in a different capacity as they progress through their career. And that doesn’t change. It just evolves.”

At Hall & Wilcox, she supports having a broad view of what a carer is within the organisation, and understanding that people can be looking after children, elderly family members and any other kind of age group.

So, when it comes to workplace inclusion, Totta recommends ensuring policies and practices advocate for and create honest conversations surrounding employee needs.

“It’s just creating an honest conversation that’s proactive rather than reactive,” she says.

“The more we have conversations, the better they’ll be.”