In December 1972, the same month the Whitlam government was first elected, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 1975 as International Women’s Year (IWY). This set in train a series of world-changing events, in which Australia was to play a significant part.

The aim of IWY was to end discrimination against women and enable them to participate fully in economic, social and political life. Fifty years later, such participation has become an indicator of development and good governance. But the full promise of International Women’s year has yet to be fulfilled, hampered by pushback and the scourge of gender-based violence.

‘The greatest consciousness-raising event in history’

Dubbed “the greatest consciousness-raising event in history”, the UN’s first World Conference on Women took place in Mexico City in June 1975. Consciousness-raising had been part of the repertoire of women’s liberation. Now it was taken up by government and intergovernmental bodies.

The Mexico City conference was agenda-setting in many ways. The Australian government delegation, led by Elizabeth Reid, helped introduce the world of multilateral diplomacy to the language of the women’s movement. As Reid said:

We argued that, whenever the words “racism”, “colonialism” and “neo-colonialism” occurred in documents of the conference, so too should “sexism”, a term that had not to that date appeared in United Nations documents or debates.

Reid held the position of women’s adviser to the prime minister. In this pioneering role, she had been able to obtain government commitment and funding for Australia’s own national consciousness-raising exercise during IWY.

A wide range of small grants promoted attitudinal change – “the revolution in our heads” – whether in traditional women’s organisations, churches and unions, or through providing help such as Gestetner machines to the new women’s centres.

IWY grants explicitly did not include the new women’s services, including refuges, women’s health centres and rape crisis centres. Their funding was now regarded as an ongoing responsibility for government, rather than suitable for one-off grants.

IWY began in Australia with a televised conversation on New Year’s Day between Reid and Governor-General John Kerr on hopes and aspirations for the year. On International Women’s Day (March 8), Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s speech emphasised the need for attitudinal change:

Both men and women must be made aware of our habitual patterns of prejudice which we often do not see as such but whose existence manifests itself in our language and our behaviour.

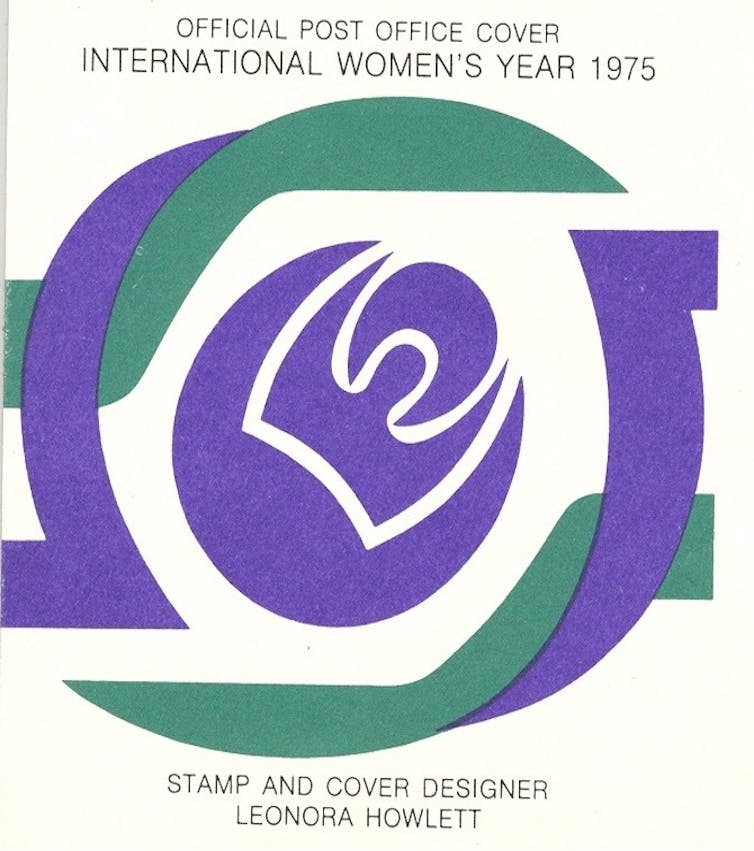

The Australian postal service celebrated the day by releasing a stamp featuring the IWY symbol, showing the spirit of women breaking free of their traditional bonds. At Reid’s suggestion, IWY materials, including the symbol, were printed in the purple, green and white first adopted by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1908 and now known as the suffragette colours.

Policy power

Inside government, Reid had introduced the idea that all Cabinet submissions needed to be analysed for gender impact. After the Mexico City conference, this idea became part of new international norms of governance.

Following the adoption at the conference of the World Plan of Action, the idea that governments needed specialised policy machinery to promote gender equality was disseminated around the world.

Given the amount of ground to be covered, IWY was expanded to a UN Decade for Women (1976–85). By the end of it, 127 countries had established some form of government machinery to advance the status of women. Each of the successive UN world conferences (Copenhagen 1980, Nairobi 1985, Beijing 1995) generated new plans of action and strengthened systems of reporting by governments.

The Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing was a high point. Its “platform for action” provided further impetus for what was now called “gender mainstreaming”. By 2018, every country recognised by the UN except North Korea had established government machinery for this purpose.

The global diffusion of this policy innovation was unprecedented in its rapidity. At the same time, Australia took the lead in another best-practice innovation. In 1984, the Commonwealth government pioneered what became known as “gender budgeting”. This required departments to disaggregate the ways particular budgetary decisions affected men and women.

As feminist economists pointed out, when the economic and social division of labour was taken into account, no budgetary decision could be assumed to be gender-neutral. Governments had emphasised special programs for women, a relatively small part of annual budgets, rather than the more substantial impact on women of macro-economic policy.

Standard-setting bodies such as the OECD helped promote gender budgeting as the best way to ensure such decisions did not inadvertently increase rather than reduce gender gaps.

By 2022, gender budgeting had been taken up around the world, including in 61% of OECD countries. Now that it had become an international marker of good governance, Australian governments were also reintroducing it after a period of abeyance.

Momentum builds

In addition to such policy transfer, new frameworks were being adopted internationally. Following IWY, the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was adopted in 1979. CEDAW became known as the international bill of rights for women, and has been ratified by 189 countries. This is more than any other UN Convention except that on the rights of the child.

All state parties to CEDAW were required to submit periodic reports to the UN on its implementation. Non-government organisations were encouraged to provide shadow reports to inform the questioning of government representatives. This oversight and dialogue relating to gender equality became part of the norm-building work of the UN.

However, this very success at international and regional levels helped fuel “anti-gender movements” that gathered strength after 1995. No more world conferences on women were held, for fear there would be slippage from the standards achieved in Beijing.

In Australia, the leveraging of international standards to promote gender equality has been muted in deference to populist politics. It became common to present the business case rather than the social justice case for gender-equality policy, even the cost to the economy of gender-based violence (estimated by KPMG to be $26 billion in 2015–16).

The battle continues

Fifty years after IWY, Australia is making up some lost ground in areas such as paid parental leave, work value in the care economy, and recognition of the ways economic policy affects women differently from men.

However, all of this remains precarious, with issues of gender equality too readily rejected as part of a “woke agenda”.

The world has become a different place from when the Australian government delegation set out to introduce the UN to the concept of sexism. In Western democracies, women have surged into male domains such as parliaments. Australia now has an almost equal number of women and men in its Cabinet (11 out of 23 members).

But along with very different expectations has come the resentment too often being mobilised by the kind of populist politics we will likely see more of in this election year.

Marian Sawer, Emeritus Professor, School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.