Defamation law is seeking to correct people’s views about the plaintiff. But it’s open to doubt that defamation law is actually any good at securing its own stated purpose of changing people’s minds about the plaintiff, writes David Rolph, from the University of Sydney, in this article republished from The Conversation.

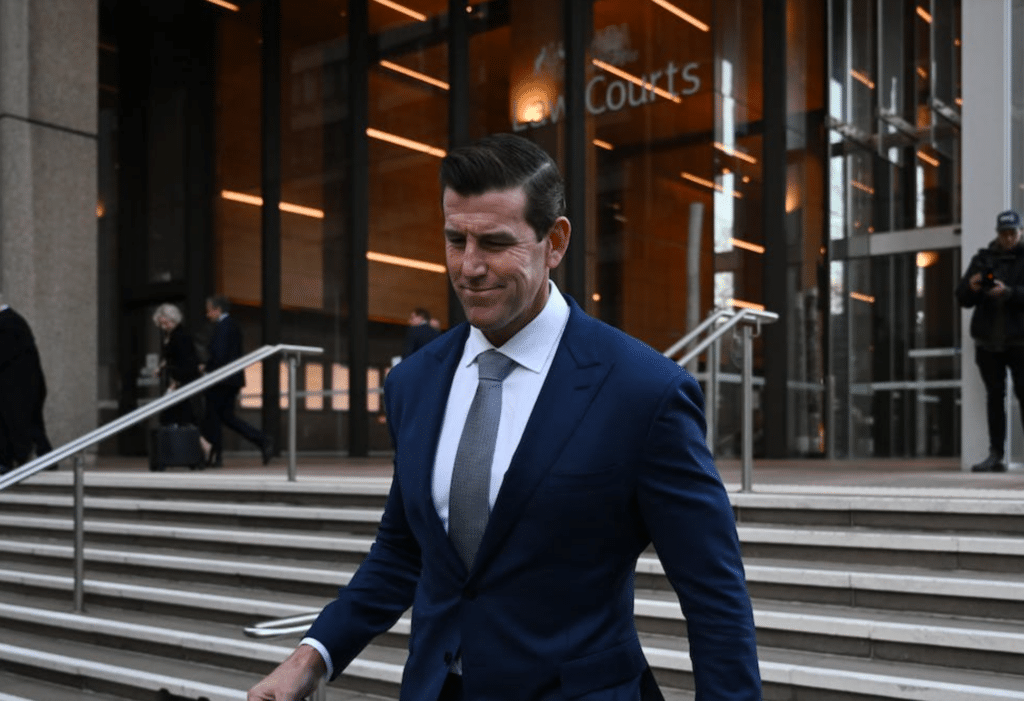

At the heart of the spectacular defamation trial brought by decorated Australian soldier Ben Roberts-Smith were two key questions.

Had the Age, the Sydney Morning Herald and the Canberra Times damaged his reputation when they published in 2018 a series of explosive stories accusing him of murder and other crimes while in Afghanistan?

And could the newspapers successfully defend their reporting as true?

Today, in Sydney, Federal Court Justice Anthony Besanko found the newspapers were indeed able to establish the “substantial truth” of key allegations around killing of unarmed Afghan male prisoners.

An appeal may still be on the cards, but this is a high-profile loss for a very prominent person. The costs will be substantial. The usual rule is that the losing party pays their own costs and those of the winning party.

So, even though people say defamation law in Australia has a reputation for favouring plaintiffs, this case shows even plaintiffs do sometimes lose defamation cases in Australia.

More broadly, this case shows how hard it is to use defamation law to repair any perceived damage to your reputation. Once a case begins, you never can control what will be said in court.

What was this case about?

The case centred on several defamatory meanings (or, as they’re known in defamation law, “imputations”) that Roberts-Smith said the papers had made against him.

Among these were that he’d killed unarmed Afghan male prisoners and ordered junior soldiers to execute others in Afghanistan between 2006 and 2012.

Roberts-Smith denied wrongdoing, but the newspapers had pleaded a defence of truth. That means to win this case, they needed to prove the meanings conveyed by their reporting – even if those meanings were unintended – were true.

Besanko, reading a summary judgment today, said the newspapers were able to establish the substantial truth of some of the most serious imputations in the case.

For other imputations, Besanko found the newspapers were able to establish “contextual truth”.

Substantial truth means what is sounds like – that the allegation published was, in substance, true. Defamation law does not require strict, complete or absolute accuracy. Minor or inconsequential errors of detail are irrelevant. What matters is: has the publisher established what they published was, in substance, true?

Contextual truth is a fallback defence. The court has to weigh what has been found to be true against what has been found to be unproven. If the true statements about the plaintiff were worse than the unproven statements, then the plaintiff’s reputation was not overall damaged by the unproven statements, and the publisher has a complete defence.

In other words, Besanko found most of the imputations to be true. And, when considered against those which were not proven to be true, the remaining unproven imputations did not damage Roberts-Smith’s reputation.

What does this case tell us about defamation in Australia?

The court heard several explosive claims during the course of this trial, including that evidence on USB sticks had been put into a lunchbox and buried in a backyard and that Roberts-Smith had allegedly punched a woman in their hotel room.

Roberts-Smith said he didn’t bury the USBs or withhold information from a war crimes inquiry and denied that he had punched the woman.

But the fact this widely scrutinised case yielded such astonishing testimony, day in and day out, shows how risky it is to use defamation law to restore perceived injury to one’s reputation.

Defamation law is seeking to correct people’s views about the plaintiff. But it’s open to doubt that defamation law is actually any good at securing its own stated purpose of changing people’s minds about the plaintiff.

The problem is the law is a very blunt instrument. It’s very hard to get people to change their minds about what they think of you.

All litigation involves risk and defamation trials are even riskier. You never can control what can come out in court, as this litigation demonstrates so clearly.

Roberts-Smith has sued to protect his reputation, but in doing so, a range of adverse things have been said in court. And whatever is said in court is covered by the defence of absolute privilege; you can’t sue for defamation for anything said in court that is reported accurately and fairly.

The 2021 defamation law reforms

The law that applies in the Roberts-Smith case is the defamation law we had before major reforms introduced in July 2021 across most of Australia.

These reforms introduced a new defence known as the public interest defence. To use this defence, a publisher has to demonstrate that they reasonably believed the matter covered in their published material is in the public interest.

As this defence didn’t exist prior to 2021, the publishers in the Roberts-Smith case used the defence of truth.

If a case like this were litigated today following these reforms, it is highly likely the publisher would use the new public interest defence.

Given the Murdoch versus Crikey case was settled, we may yet wait some time to see what’s required to satisfy the public interest test in a defamation case.

But as today’s decision demonstrates, sometimes the truth alone will prevail.

David Rolph, Professor of Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.