Fewer cases, fewer deaths and earlier lockdowns can be found in the data across nations with women at the helm, write Supriya Garikipati, from University of Liverpool and Uma S Kambhampati, from University of Reading in this article republished from The Conversation.

Over the last few months, there has been much discussion of leadership during the pandemic. What constitutes good leadership? Who has performed better and which countries have been worse? One pattern that emerged early on was that female leaders were seen to have handled the crisis remarkably well. Whether it has been New Zealand under Jacinda Ardern or Taiwan under the presidency of Tsai Ing-Wen or Germany under Angela Merkel, female-led countries have been held up as examples of how to manage a pandemic.

We decided to investigate whether this anecdotal perception stands up to more systematic scrutiny. To do this, we analysed how leaders around the world reacted to the early days of the pandemic to see whether differences in performance can be explained by differences in policy measures adopted by male and female leaders.

Two qualifications need to be kept in mind: first, we are only at the start of the pandemic and much could change in the next few months. Second, the quality of data currently available is limited. Inadequate testing means that case numbers are probably an underestimate. The way deaths are registered also varies across countries.

There are far fewer female-led countries in the world when compared to male-led countries. Just 10% in our sample of 194 countries have women as national leaders. Given the small number of female-led countries, the most appropriate way to consider their performance is to match them with “similar” male-led countries. We did this by matching countries with similar profiles for the socio-demographic and economic characteristics that have been seen as important in the transmission of COVID-19.

In the first instance, we compared countries with similar GDP per capita, population, population density and population over 65 years. We then extended our matching variables to include three other characteristics: annual health expenditure per capita, number of tourists entering the country and gender equality.

These comparisons threw up clear differences between female-led and similar male-led countries during the first quarter of the pandemic (up to mid-May).

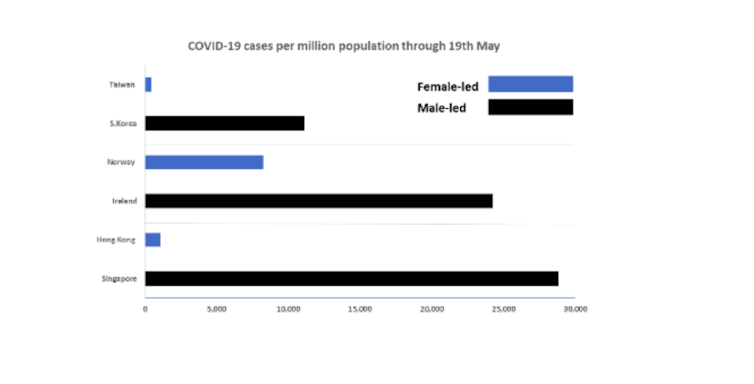

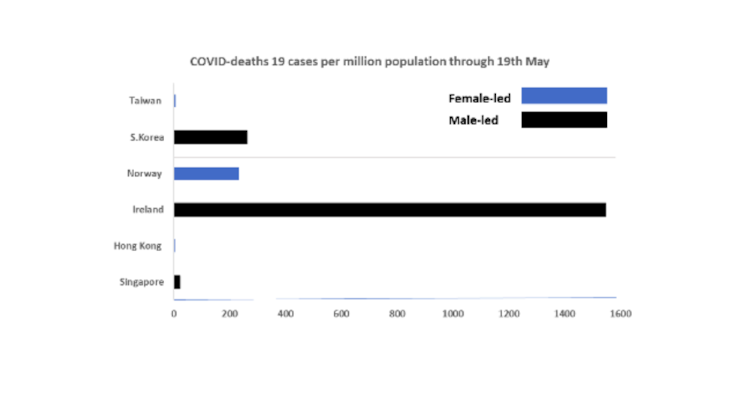

Hong Kong, which is led by a woman, recorded 1,056 cases and four deaths while Singapore, which has a similar economy and comparable demographic characteristics, but is led by a man, recorded 28,794 cases and 22 deaths in the same period. Similarly, Norway, led by a woman, had 8,257 cases and 233 deaths, while Ireland, led by a man, recorded 24,200 cases and 1,547 deaths. Taiwan recorded 440 cases and seven deaths while South Korea had 11,078 cases and 263 deaths.

Countries led by women have performed better, especially in terms of deaths and this is true whether we consider the nearest comparable nation, the nearest two, three or even five. Belgium is an outlier, having appeared to perform badly on cases and deaths while led by a woman. But despite its inclusion, the overall results regarding women-led countries stands.

For example, Finland was better than Sweden, Austria and France in terms of both cases and deaths. Germany was better than France and the UK. Bangladesh fared better than the Phillippines and Pakistan in terms of deaths.

Taking risks

Analysing what might cause this differential performance, we find that the female-led countries locked down significantly earlier than the male-led countries. Female-led countries like New Zealand and Germany locked down much more quickly and decisively than male-led ones like the UK. On average, they had 22 deaths fewer at lockdown when compared to their male counterparts.

We considered whether these results might imply that women leaders are more risk averse. Literature on attitudes to risk and uncertainty suggests that women – even those in leadership roles – appear to be more averse to risk than men.

Indeed, in the current crisis, several incidents of risky behaviour by male leaders have been reported. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro dismissed COVID-19 as “a little flu or a bit of a cold” and UK prime minister Boris Johnson said he “shook hands with everybody” on a hospital visit. Both men subsequently contracted the virus.

However, this is a simplistic explanation. While women leaders were risk averse with regard to lives, they have clearly been prepared to take significant and early risks with their economies by locking down early. So women leaders seem to have been significantly more risk averse in the domain of human life, but more risk taking in the domain of the economy.

We find some support for this idea in studies that examine risk-taking behaviour when lotteries are framed as losses. Men are found to be more risk averse than women when lotteries are framed as financial losses rather than gains. It could well be that the relatively late lockdown decisions by male leaders may reflect male risk aversion to anticipated losses from locking down the economy.

Leadership style

Another explanation of gender differences in response to the pandemic is to be found in the leadership styles of men and women. Studies suggest that men are likely to lead in a “task-oriented” style and women in an “interpersonally-oriented” manner. Women therefore tend to adopt a more democratic and participative style and tend to have better communications skills.

This has been in evidence during this crisis in the decisive and clear communication styles adopted by several female leaders, whether it be Norway’s prime minister Erna Solberg speaking directly to children or Ardern checking in with her citizens through Facebook lives.

Our findings show that COVID-outcomes in the early stages of the pandemic were systematically and significantly better in countries led by women. This, to some extent, may be explained by the proactive policy responses they adopted. Even accounting for institutional context and other controls, being female-led has provided countries with an advantage in the current crisis.

Supriya Garikipati, Associate Professor of Development Economics, University of Liverpool and Uma S Kambhampati, Professor of Economics; Head of School, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.