The Victorian Government is planning to decriminalise sex work, as New South Wales has already done. Victoria’s current laws provide for legal brothels, but the licensing regulations and some brothel owners’ drive for profits have resulted in a two tier system where there are more illegal brothels than legal ones, and many sex workers choose to work alone. As a result sex workers are put at risk in numerous ways.

Fiona Patten MP has conducted a targeted review of the existing legislation in an effort to find the best way to improve occupational health and safety for sex workers. It’s a welcome move after over a century of punitive measures, but it will not remove discrimination unless community attitudes change along with the law.

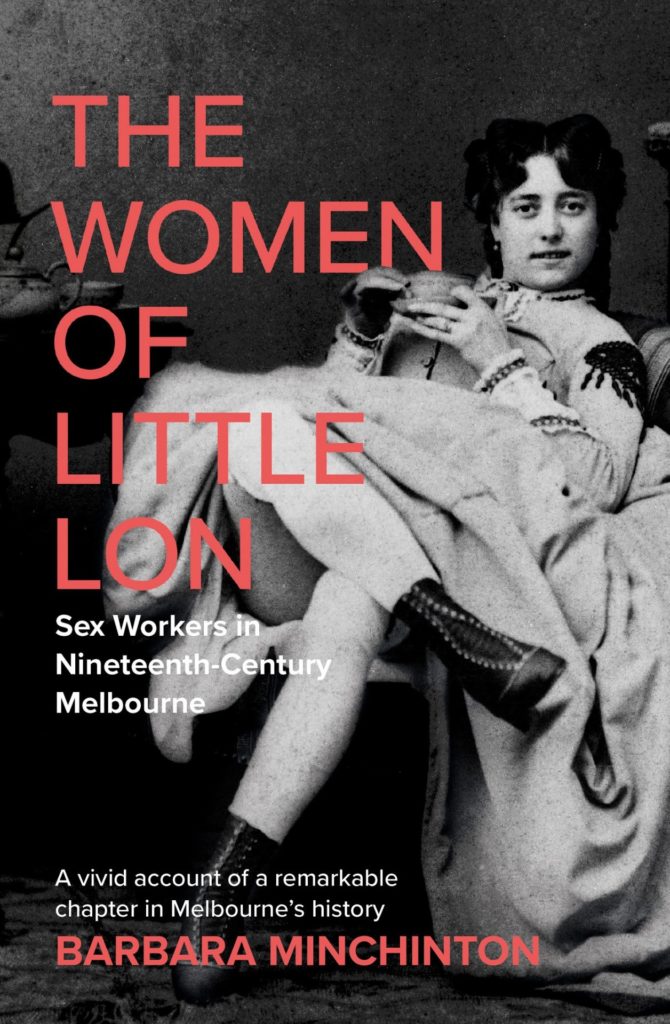

A study of female sex workers in Melbourne in the nineteenth century, The Women of Little Lon, reveals that sex work itself was not illegal in Victoria until 1891 when street-walking became a crime, and brothels were not banned until 1907. Yet sex work had still been policed, using laws against drunkenness, rowdiness and vagrancy to control where brothels could be located and where sex workers could solicit clientele. Periodic outbursts of moral outrage from ‘respectable’ members of the public could result in women being imprisoned for up to twelve months on charges such as ‘disorderly behaviour’.

So sex work legislation is only part of the problem. In the nineteenth century public attitudes gradually shifted from turning-a-blind-eye tolerance to crusading prejudice, resulting in harsh criminal provisions being enacted around the turn of the century. Through the twentieth century laws changed and legal brothels were introduced, but for sex workers the stigma and threats associated with their occupation continued.

In conducting the review Ms Patten has consulted with key stakeholders, paying particular attention to sex workers themselves.

‘If you do not listen to the views and the ideas of people who are the heart of any industry, you are wasting your time,’ she said.

We have no way of consulting the views of sex workers in the nineteenth century, but The Women of Little Lon explores the patterns and conditions of their lives. By leaving moral judgement behind it shows how the expensive brothels run by the flash madams such as Sarah Fraser and Madame Brussels provided employment and a safe space for some women escaping domestic violence.

It also shows women choosing sex work rather than domestic drudgery and factory work with their long, poorly paid hours, and single mothers raising children in an era when no other work was available to them. There are also stories of feisty women getting married after a few years on the streets with their friends. For many of these women the sex industry was a short-term employer, but there were others who spent a lifetime in the trade, moving from working the streets to running their own brothel. For the unlucky ones sex work could also be part of a lengthy struggle with alcoholism and disease, and many lost the battle.

Sex work for all of these women was a way to earn a living, yet they were judged morally corrupt by the same world that ensured that there was plenty of work for them, and it was the moral judgement as much as the law that affected the quality of their lives. Their work was not illegal, but they could still be charged with being disorderly for dancing in the street and their children could be labelled ‘neglected’ and taken away on the basis of their mother’s reputation.

Judgement operates in the same way today. A bank might agree to a sex worker opening an account, but a company that leases EFTPOS machines might refuse to provide one that enables a sex worker to process card payments. Attitudes are as influential now as they ever were.

Victoria has a unique history of sex work. The closure of Melbourne’s brothels in 1907 did not lead to the industry being controlled by a criminal underworld as it was in Sydney, but it did lead to corruption and much poorer working conditions for sex workers.

In the nineteenth century brothels were mostly run by women, and female sex workers had more freedom than their respectable sisters had to walk in the street and go alone to theatres and entertainment venues. Once the legislation changed, men largely took control of the business either through pimping or protection rackets. Today there are more men than women running Melbourne’s brothels.

Through telling women’s stories, The Women of Little Lon provides us with insight into how public attitudes towards sex work influenced both the day-to-day circumstances of women’s lives and the legislation governing the industry in the nineteenth century. There are substantial lessons in it for today’s legislators.

If sex workers are to be free of the debilitating constraints that arise through stigma and discrimination, the industry needs to be regulated in the same way as any other – for safety, for health and for probity. Not for morality. And the community needs to accept that consensual adult sex work is a legitimate way to earn a living.

Find out more about The Women of Little Lon: Sex Workers in Nineteenth-Century Melbourne by Barbara Minchinton, at Black Inc.