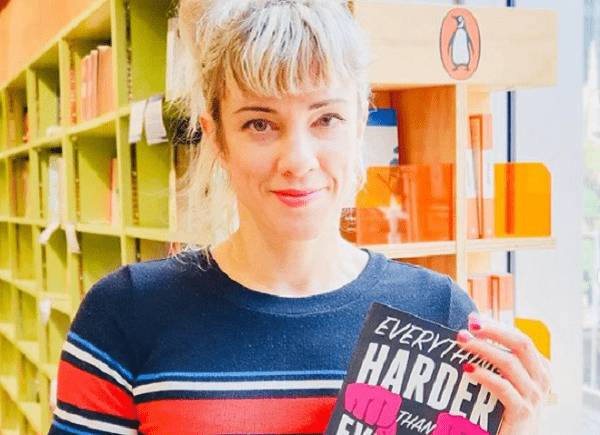

In her new book, Everything Harder Than Everyone Else, Jenny Valentish asks people who push their bodies to extremes why and how they do what they do.

For some, it’s about leaving the comfort zone of modern life. For others, they feel that if they can forge through a gruelling ultramarathon or suspend their body from hooks, they can survive anything in their day-to-day life. And for others, it’s drawing on childhood adversity that gives them the stamina to withstand great discomfort.

Still fascinated with the idea of endurance after writing her addiction memoir Woman of Substances, Jenny decided to herself become an amateur kickboxer, in parallel to meeting the larger-than-life characters of her book.

The following is an excerpt from Everything Harder Than Everyone Else.

When I took up fighting, it quickly became apparent that my ego would be my gnarliest opponent. I was forty-three, with a career in journalism based on independent decision-making, so I was far less amenable to being told what to do than a twelve-year-old might be. And as an adult I’ve had a tendency to avoid activities in which my performance would be anything less than above average.

It’s a testament to my ego that I pay for a personal Muay Thai kickboxing trainer about thirty times more frequently than I attend a Muay Thai class. One of my trainer’s names, back in his fighting days, was ‘The Human Bear Enclosure’. Since then, Nick has stacked on another 30 kilograms of muscle in his reincarnation as a pro-wrestler called Gore. He walks like a blockbuster bad guy, arms held at bay by his swollen lats. Ordinarily, trainers transmit motivational slogans: sentiments that spill over into their social media accounts. Nick’s Instagram profile is nihilistic in tone, and suggests that training is merely a prelude to death. One post is of a bin, with the suggestion you put your hopes and dreams in it.

Muay Thai is the ‘art of eight limbs’, a combat sport that originated in the sixteenth century. As I pirouette around, throwing legs, Nick keeps his face expressionless as a bouncer – which he also is. I ask him what he and the other bouncers talk about, stood outside a door for eight hours. ‘Girls, fighting, movies, how much you hate patrons,’ he says. ‘Obnoxious stuff.’

Things get more inventive as our sessions continue. Sometimes I’m made to shadow-box with thumb tacks taped to my heels, to keep me on the balls of my feet. Other times, as I do sit-ups, he crouches next to me and smashes me in the guts with a kickpad. Each time he’s about to slam the pad down, I hear him take a sharp breath, maybe for effect.

For the past few months we’ve worked on pads – he holds them, I punch and kick them – and it hasn’t been necessary to think for myself, nor hold back on the power. Today, we’re sparring for the first time. Playing, he emphasises. But like every other wet-behind-the-ears student before me, I’m pistoning in hard and fast.

Nick catches every kick and blocks every punch, and occasionally sweeps me to the canvas. ‘You’re telegraphing all your moves and any time you have made contact has been a fluke,’ he says. A couple of times, he backs himself against the ropes and buries his head in his forearms. Faced with this invitation and the self-efficacy it requires of me, I panic. His grin is just visible through his wrists. Rather than calculate my opportunity, I whale at him ineffectively. Despair turns to hopelessness turns to blind kicking. Sometimes I kick upwards – like a lever – between his legs. That’s not a move.

In wrestling terms, if you go too rough on your opponent, they might give you what’s known as a ‘receipt’. It’s an act of retaliation, twice as hard, to smack you back down to size. As I flail in impotent rage, Nick starts issuing his receipts: repeated chops to my leg, which I should be noticing is a pattern. They’re much harder chops than our official ‘just playing’ capacity, and I make that known by swearing each time one lands. At this, he goes even harder. Eventually the buzzer sounds. Nick leads me by one arm till I’m against the ropes. Unable to avert my gaze, I let my eyes glaze over.

‘You’re getting too emotional,’ he says. I’m not, I think indignantly, as emotions swarm all over my body. He must mean ‘angry’. Although, come to think of it, I could cry right now. ‘You need to be cold, calm and ruthless,’ he continues, up in my face. ‘If you come at me like that, you leave me no choice but to respond.’

So fighters must have ‘heart’, as they say, and yet, their hearts must be devoid of emotion. Devoid of the purest, most cleansing hatred I think I must ever have felt forge through my veins. In my last book, I wrote about my abundance of this particular emotion. The rage. The fucking rage! It’s always there, inflating inside me, like the Hindenburg awaiting a match. Why does Nick not appreciate the powerful raw material I’m working with?

When I leave the gym, pain radiates from my thigh, up through some mysterious new elevator-of-awful in my torso, and into my chest. Halfway down the road, I give up on hobbling and get an Uber. At home, I cry into a neat gin and smear myself in Tiger Balm, and think: There’s no better way to learn how fragile you really are than building up your physical and mental strength for months, only to have it crumble at the first test.

Muay Thai was supposed to be character-building. I had taken it up when I was called on to make a police statement about a historic crime, which would be a lengthy process over which I had no control. Making this report, I decided, must also signal the end of the passive state of ‘victim’ I had internalised. Walk tall, I chastened myself, wandering aimlessly through London after I’d completed the police interview. Taller. See how different that feels? Wow. Bring on the new era! It felt forced, but I don’t like having no control. And unless you’re unlucky enough to be sick – or maybe until you’re unlucky enough to be sick – you can at least control your body. Other women I meet when training have similar reasons, growing up in homes of family violence being one I hear repeatedly.

Before too long, I will have to spar again, sacrificing my self-respect anew. Maybe these knocks to the confidence could be likened to hypertrophy, the process of weightlifting: you put the muscle tissue under stress and cause micro tears. It’s only through gaining and recovering from these tears that the muscle grows.

This is an edited extract from Everything Harder Than Everyone Else by Jenny Valentish. Published by Black Inc. on 1 June (RRP: $32.99). Available online or in all good book stores.