The education and career choices that females make has long been a focus for International Women’s Day – in fact, the very genesis of the day is to encourage women to chase their dreams, to be inspired by those who have gone before and to make brave choices.

STEM and STEAM have been catch-phrases in this debate, and it’s encouraging that we are slowly moving the dial on female enrolments in the sciences, technology, engineering and math.

In contrast, I’m saddened that this is not the case for economics. The Reserve Bank of Australia’s Head of Information, Jacqui Dwyer gave an insightful speech in 2018 outlining the declining popularity of economics both at school and university, as have Assistant Governor (Economic) Luci Ellis and Head of Economic Analysis Alex Heath in recent years.

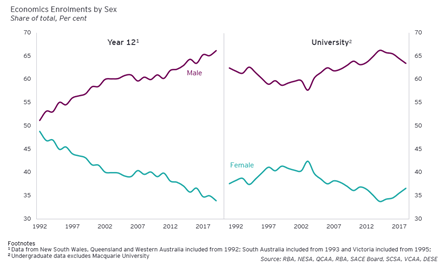

Enrolments in economics has declined overall at both the Year 12 level and university since the early nineties (partly because of rising popularity of business and commerce subjects), but where I see the worrying trend is that the demise has been faster for females than males. The ratio of males to females has halved from roughly 1:1 in the 1990s, to 2:1. In contrast, the gender ratio for business studies has remained quite stable and close to 1:1.

Where are the female economics students going?

An RBA survey of Year 10, 11 and 12 students in 2020 reveals that female students are more likely than males to perceive economics as important in society and used for social good, but less likely to find it interesting. Importantly, the survey also showed interest was the number one reason to elect economics as a subject. In addition, females were less likely to have a good understanding of what economics is or a clear idea of potential careers.

We know that diversity drives better questions, more comprehensive answers, creative solutions and better business outcomes.

Which means it is a concern that economics as a profession is losing, not gaining, diversity. Not only are the statistics on gender balances confronting but over half the students studying economics at university are from high socio-economic families, while over 90 per cent of students are in urban areas – raising even further concerns about the potential lack of diversity in the next generation of economists.

I often say that studying history allows us to learn from the past to make better decisions in the future; teaching geography helps us to understand that physical and social world we live in; economics – which is not compulsory at school – shows us how to allocate resources to drive change, efficiency and fairness, and provides an analytical framework to understand the ‘why’ behind individuals actions and decisions.

But to do that well, requires diversity in the profession.

One of the explanations for the decline in student interest in economics in Australia is that the economic backdrop was benign for so long. It’s been nearly thirty years since the last recession. When the economy is stable, times are good, there is less interest in changing the status quo.

Now we find ourselves in a position where all Australians, young and old, face the challenge of rebuilding the economy, and taking the opportunity to build a better, more resilient, more inclusive, more equitable, more climate aware economy. One of the lasting legacies of the recovery from the Global Financial Crisis was rising inequality. Surely, we don’t want to repeat that mistake.

To meet this challenge is going to require a diverse generation of economists.

So, let’s get a more diverse economic voice!

We’ve all heard the quote “You can’t be what you can’t see”. Personally, I don’t ascribe to that, but I do believe it’s easier to be what you can see, even if that needs improving on.

Dwyer argues – and let’s be honest, we all see it – that “too often they [economists] are a homogenous bunch”.

That’s changing – there are some amazing, leading female economists in Australia. And the Reserve Bank of Australia, Economic Society of Australia and Australian Business Economists and others are being proactive, looking to engage with students and show them why economics is so important to our world.

We need to generate, support and inspire a diverse pipeline of economists to ensure that the right questions are asked to deliver inclusive, equitable and sustainable economic growth.

I myself have two daughters. Full disclosure. One studied economics in Year 12 but not at university and a younger one who has avoided commerce, economics and business. But I’m not accepting defeat, and as many family, friends and colleagues will tell you I’m always looking for the opportunity to inspire budding young economists.

So, is it possible that COVID-19 can make economics cool again for all young Australians?

We know that young Australians are interested in building a better working world, this generation is one of the most vocal we have seen in decades when it comes to driving change: climate change and the energy revolution; equality and inclusiveness; standard of living and purposeful employment; housing affordability; building the cities and infrastructures we need and want, to name a few.

So what we need is to get better at showing young Australians that economics is at the front and centre of these debates? Who wouldn’t want a chance to leave a legacy and change the world?

The views reflected in this article are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organisation or its member firms.