The first was the death of her “little big sister”, Rowena, when Clare was just five. The second was having her weight singled out, ridiculed and dissected, openly, from virtually the same age.

There were five siblings in the Bowditch clan, all spaced exactly 18 months apart. A “rare triumph of the rhythm method” is how Clare describes it. Rowena, Rowie as she was known to her family, was fourth, and Clare was fifth. Anna, Lisa and James preceded them.

Rowie developed what was considered a mystery illness at age 5 that slowly claimed her appetite, her sight and then her ability to walk. Six months after the symptoms first appeared she was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit in Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital where she stayed for the rest of her life, two years. The simplest explanation is a very rare form of multiple sclerosis.

Clare’s parents desperately wished they could have Rowie home with a fulltime nurse but it wasn’t the done thing. The family adjusted to a new routine in which their time was split between hospital and home. Their community stepped up to “carry them” through.

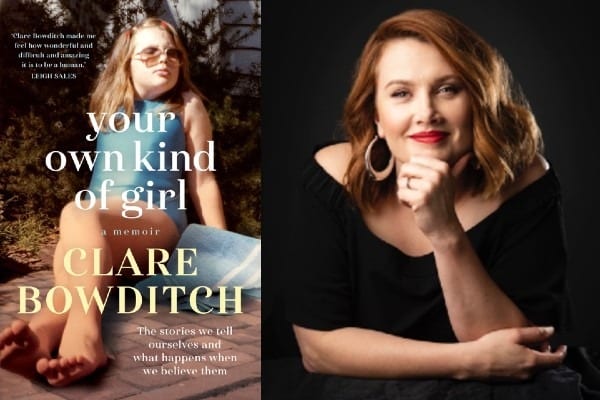

Bowditch captures the grief this presented with extraordinary clarity in her memoir, Your Own Kind Of Girl. She was so young when it happened that her words stitch together the various details and stories her family members have recounted from that time.

“An important part of this story is being a sibling who lost a sibling,” Bowditch says. “The grief does change but the love that existed with her that’s no longer here? That’s really difficult to talk about.”

As a family Bowditch says they tended to ‘live it out’ rather than talk about it which made writing this part of her memoir particularly emotional.

“I needed to check in with my family. I was just telling it from my childhood perspective. They understood why I would do it and it wasn’t easy, but they are very encouraging of me telling this.”

She gave a copy of the draft chapter to her mum to have a read but was terrified when her mum handed it back with about 59 post-its of changes.

“Most were grammatical corrections though!”

From every vantage point Rowie’s illness is heartbreaking: impossible to fathom. It is especially flooring to picture this cruel upheaval, losing a beloved sibling and watching her family come to grips with losing a child, through the eyes and mind of someone just five years old. The trauma haunted Clare: she felt guilty and scared and sad and burdened.

The fact she went on to face another punishing battle no child should compounded the impact. From a very young age Clare was forced to grapple – explicitly – with the toxic idea that her weight was the major barometer of her worth.

It wasn’t just that kids teased her for being big. Adults called her fat too. To her face. When she lost weight, her primary school teacher and mums of her friends asked for photocopies of her diet. She was treated differently. It was clear she was better liked when she was thinner. The warm glow of approval was intoxicating. But it was also unsettling for her young mind: she was the same person regardless of the number on the scales so why was it such a big deal? It set in motion a vicious cycle: constant dieting, binging, self-loathing. It went on for years.

Clare Bowditch on anxiety, food and grief https://t.co/1W21MVsJwg #RNLifeMatters

— ABC Radio National (@RadioNational) October 29, 2019

At 21 Clare found herself living overseas in a state of despair: her heart had been broken, she was terrified of dying, of other people dying, she was overwhelmed with the battle she couldn’t resist with her weight and body, she was panicked and unable to sleep. Eventually friends had to put her on a plane back to Australia. Despite not wanting to burden her family, Clare acquiesced. Her parents collected her and bundled her up.

One of the small life rafts she built in moving beyond that dreadful time was a promise to herself that if she survived she would one day write a book about it.

“If I recovered from the terrible spot I was in I promised myself I would pass on this story. I promised myself that because it gave me something to keep going for and to make me feel proud.”

Twenty-two years later she has delivered on the promise and the resulting memoir is breathtaking.

“These stories were difficult to tell in part but without telling the whole it doesn’t make sense,” she says.

The writing itself was incredibly challenging.

“I wanted to give up many times but that would have counteracted the purpose of the book. The emotional weight of sitting back in the really difficult times in my life, questioning was there a purpose in going back there, was difficult.”

Trying to navigate that while also attempting to keep a happy, functioning family with her three children added another dimension.

“It was genuinely thrilling at the beginning and then it was like I was in the belly of a whale. I was in a dark little cave and I knew I’d come out the other end but I didn’t know how dark it would get.”

On Monday, the official publication date of Your Own Kind Of Girl, one of her sons raced into her room.

“‘Mummy it’s book release day! You did it!’ It made me so emotional. We did it. He’s right.”

Between the age of 21 and 43 Clare didn’t just change the stories that nearly broke her: in addition to creating own family, she has also built a career as one of Australia’s most successful musicians. But she laughs that hers is the least rock-n-roll book ever published.

“There’s not much of the celebrity memoir thing. There’s not terribly much drug-taking or sex!”

Extract from @ClareBowditch's brilliant new memoir. It's unlike any celebrity autobiography I've ever read. Not a hint of self-aggrandisement or name dropping. https://t.co/yKfRSBEH7c

— Annabel Crabb (@annabelcrabb) October 25, 2019

And yet it’s perhaps one of the most powerful celebrity memoirs precisely for that reason. She writes with brutal honesty about the things she has battled and grappled with. Things both in and out of her control. Things so many other women will relate to. Anxiety. Weight. Food. Grief. Love.

“This is a story about the stories we tell ourselves and what happens when we believe them,” she says. “Even though we cannot change the circumstances – the weather, our loved ones’ lives, what time a train comes – and we can’t even change the stories we start with, but where we have a choice is the story we tell ourselves.”

The story Clare Bowditch has chosen to tell us is pretty extraordinary.