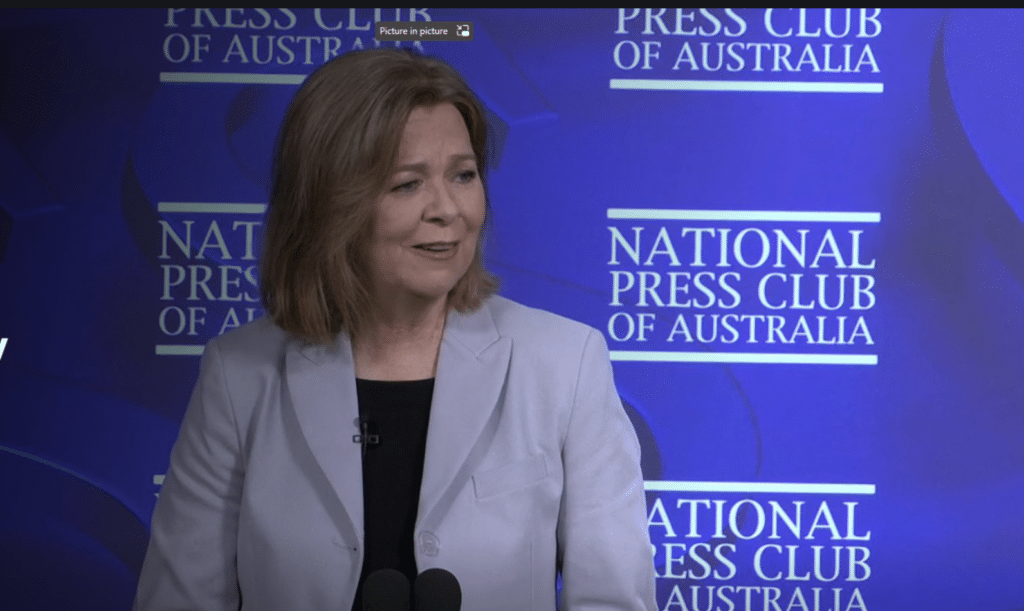

ACTU boss Michele O’Neil discussed a huge range of topics at the National Press Club on Tuesday, but there was one line from her that particularly stood out: “Work is important but so is the rest of your life.”

O’Neil was responding to a question about more Australian businesses trialing the idea of the four-day work week, following larger trials that have occurred across the world.

Representing the unions, O’Neil said she was in favour of more four-day trials, and noted some of the findings internationally that have highlighted better productivity, as well as better employee well-being and satisfaction when working this way. “There’s something not working here,” she said about how we are currently working. “We should be able to have another look at work and say, ‘how do we get this right?”

O’Neil wasn’t at the Press Club to discuss the benefits of the four-day work week. Rather, her presentation was to push the ACTU’s plan for a national energy transition authority to be included in this year’s federal budget, which is just six weeks away.

But the four-day work week is relevant, as is acknowledging the lives that “workers” have outside of work – if we want to get anywhere close to bringing in the skills we need for the green energy transition ahead.

O’Neil pointed to the hundreds of thousands of jobs that could come from decarbonising in Australia, and the need for a just transition that relies on national coordination, with planning and input from local communities. She said that the political football of climate change — particularly from the previous government — has left a crucial element missing from the national response: how the workers, families and communities that are most affected by decarbonisation are supported.

She wants to shift from the idea that we need to choose between jobs and addressing climate, saying that we have a duty to address both. And she took aim at the previous federal government, which she said “weaponised this false choice in order to shrug their responsibility to act on climate change.”

“Decarbonising our economy could generate hundreds of thousands of good jobs, healthier and more equitable communities, and a renewed national prosperity, all while safeguarding Australians against spiraling climate disasters,” she said.

But seizing these opportunities requires “building an economy that restores the planet on which it relies”, transforming the “extractive economy” to a “circular economy powered by clean energy.”

We have, according to the science, just three decades to get this right — but just years to commence the transition in a serious and meaningful way.

O’Neil pointed to the need to guarantee that workers affected by the transition — such as through the closure of coal-fired power plants — have adjustment packages that give them access to quality, secure, safe jobs.

But as we found in our recent report, The Climate Load, this is a transition that can’t be done without tapping into the full potential of the population, particularly in addressing women’s workforce participation and removing some of the barriers in the way of women pursuing and sustaining careers in areas that we know are desperate for skilled workers: like engineering, technology, and construction.

Engineering, for one, is key to the renewable energy transition — but it’s also an area identified as experiencing a “critical worker shortage”. Just 13.1 per cent of the sector is female, according to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency. We must consider what’s holding women back from joining and continuing careers in this sector.

Construction is also facing skill shortages — and a key area for the transition. It’s also one of the most male-dominated industries in the country, showcasing again the opportunity that could emerge from removing some of the barriers to women from having ambitions to get involved, as well as the challenges in the way of women being able to access full success and longevity in such careers.

Which brings me back to the four-day week — can a four-day work week support the transition mission, especially in getting more women involved? And what more can be done on this idea that “work is important but so is the rest of your life” to access the full potential of the population?

Further, can the four-day work week support people in other industries to get the training and education they need to make a shift into careers related to the energy transition?

Are there further changes around the archaic structures around how we work that employers should be addressed to support those workers who are set to be directly impacted by decarbonisation?

On addressing getting more women involved, there are bigger conversations needed that go beyond just “inspiring” girls and young women to pursue careers relevant to renewable energy. As we’ve seen for years now in STEM, where just 27 per cent of the entire workforce is female, there remains significant barriers in the way for women in pursuing STEM careers. Such barriers include discrimination, sexual harassment, pay inequity, a lack of flexible work, and more. These are barriers that can be addressed and must be considered as we think about the huge shift ahead.

Barriers that should be considered by any national energy transition authority that emerges in the future.

What good is mobilizing a population for the renewables transition, if they end up burnt out or leaving their work and professions they’ve trained and gained experience for, due to not being able to access what they need outside of work?

These are just some of the considerations that need to be made to ensure that most impacted by decarbonisation have the support they need, and also that everyone has the chance to access the opportunities that can come from the energy transition.

As O’Neil said on Tuesday: “The transition will not be fair by accident. It will only be just if it’s someone’s job to make it just.”