In terms of academic advantage, we know, from our research and other studies that explored similar questions, there is little evidence to show independent schools offer any. It is likely children will do equally well in any school sector, writes Sally Larsen and Alexander Forbes from University of New England, in this article republished from The Conversation.

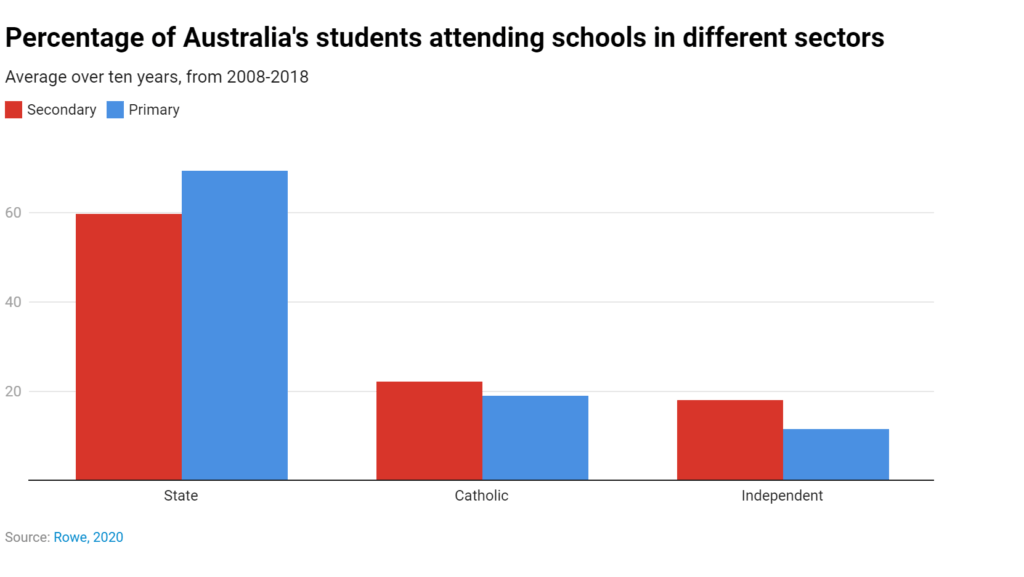

In Australia, around 30% of primary and 40% of secondary school children attend a private, or independent, school. School fees vary widely, depending on the type of private school and the different sectors that govern them. Catholic schools generally cost less than independent schools where families can pay fees of more than $40,000 per year.

Despite the term “independent school”, all schools in Australia receive government funding. On average, Catholic schools receive around 75% and independent schools around 45% of their funding from state and federal governments.

Research shows parents believe private schools will provide a better education for their children, and better set them up for success in life. But the evidence on whether this perception is correct is not conclusive.

What does the research say about academic scores?

Our recent study showed NAPLAN scores of children who attended private schools were no different to those in public schools, after accounting for socioeconomic background.

These findings are in line with other research, both in Australia and internationally, which shows family background is related both to the likelihood of attending a private school and to academic achievement.

While there may appear to be differences in the academic achievement of students in private schools, these tend to disappear once socioeconomic background is taken into account.

An analysis of 68 education systems (mainly countries, but some countries only include regions which are known as “education systems”) participating in the 2018 Programme for International Assessment (PISA) tests showed attendance at private schools was not consistently related to higher test performance.

The OECD report says:

“On average across OECD countries and in 40 education systems, students in private schools […] scored higher in reading than students in public schools ([…] before accounting for socio-economic profile)[…] However, after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile, reading scores were higher in public schools than in private schools […]“

Do private schools improve student achievement over time?

Another argument used to support Australia’s growing private school sector is the idea private schools actually add value to a child’s education. This means attending a private school should boost students’ learning trajectories over and above what they might have achieved in a public school.

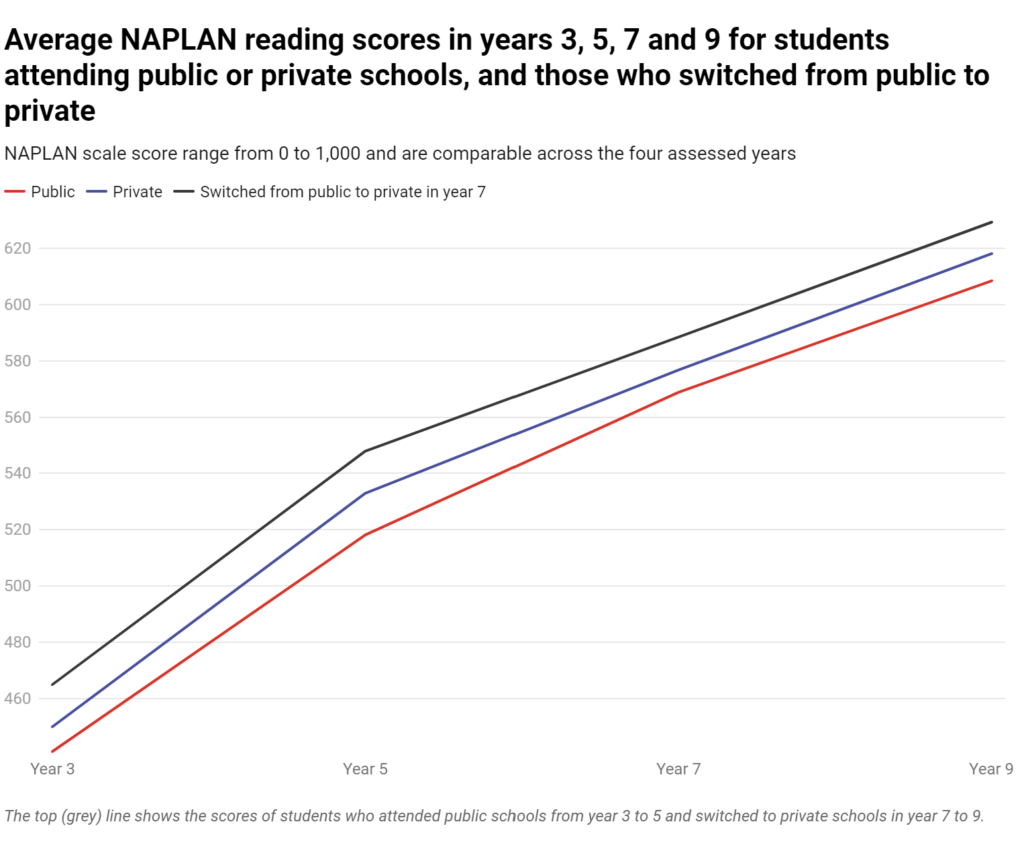

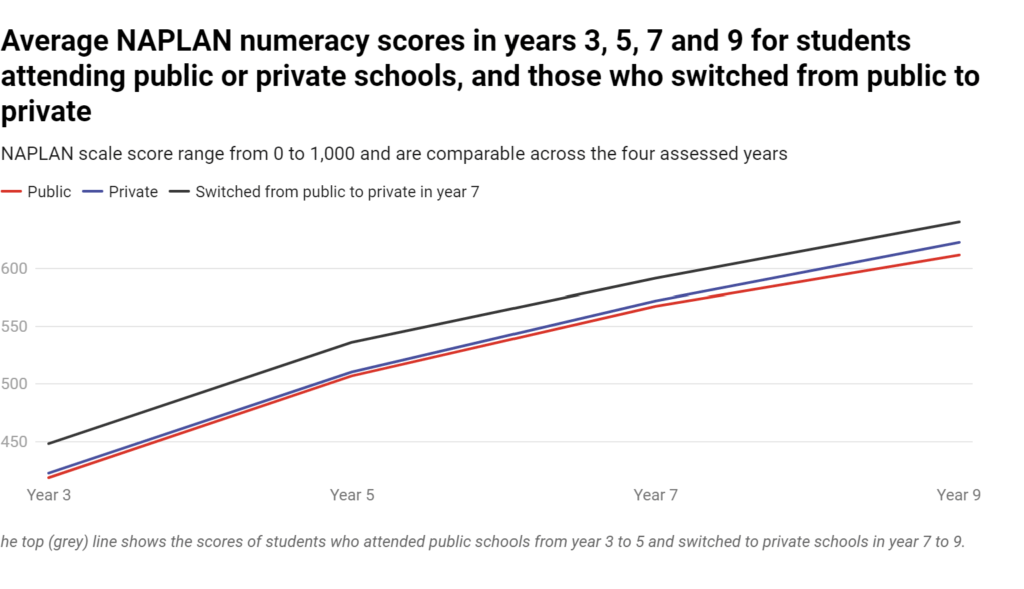

Our research is the first to examine whether students differ in learning trajectories across the four NAPLAN test years (3, 5, 7 and 9) depending on the school type they attended.

We compared the NAPLAN scores of students who attended a public school, a private school and those who attended a public school in years 3 and 5 and then a private school in years 7 and 9. The students in the latter group scored highest in reading and numeracy tests in each of the four NAPLAN test years.

This group outperformed students who attended private schools at all years, and students who attended public schools at all years. But there was no evidence that making the switch to a private school added to students’ learning growth.

These high-performing students were already achieving the highest results in public school before they left for private school in year 7.

This suggests private schools may be be enrolling the highest achievers from public primary schools.

Other analyses in our paper showed that once socioeconomic background of these students was taken into account, apparent achievement differences between school sectors were no longer present.

The other interesting point is that there were no differences in achievement trajectories between the groups. So, making the switch to private schools in year 7 did not affect the gains students were making in NAPLAN over time. Students in public schools made just as much progress as their peers who attended private schools.

This undermines claims private schools add value to students’ academic growth.

What about other private school benefits?

Some Australian research has shown students who attend private schools are more likely to complete school and attend university, and tend to attain higher rankings in university entrance exams. Indeed, the recent announcements of NSW students’ HSC results showed almost three-quarters of the 150 top-ranked schools were independent.

The concentration of higher-achieving students in private schools could also magnify any peer effects on students’ decisions about future career paths or attending university.

Nonetheless the research on these questions is not definitive: it is very difficult to separate out the effects of background characteristics of students and the effects of the school sector given that more advantaged students tend to concentrate in private schools.

Some Australian research has shown the characteristics of students before they enter private schools have a larger effect on their aspirations, behaviour and attitudes than the school.

Rethinking the system?

While the capacity for parents to choose a school that best suits their child is often seen as an advantage, many disadvantaged families are a lot more constrained in their ability to choose, and pay for, private schools.

Students attending private schools may have access to other non-academic benefits, such as more opportunities for sports, excursions and other extracurricular activities.

But in terms of academic advantage, we know, from our research and other studies that explored similar questions, there is little evidence to show independent schools offer any. It is likely children will do equally well in any school sector.

Sally Larsen, PhD candidate, Education & Psychology, University of New England and Alexander Forbes, PhD Candidate in Psychology, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.