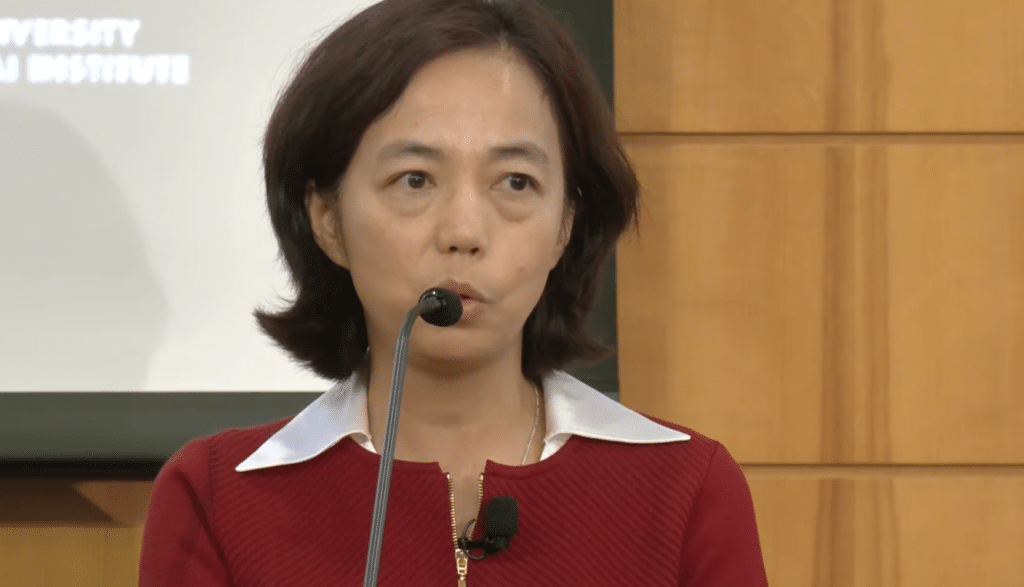

Fei-Fei Li is one of the most prominent women in the heavily male dominated field of artificial intelligence. Jane Goodall, from Western Sydney University shares this review of her book, The Worlds I see, in this article republished from The Conversation.

Public debate on Artifical Intelligence has escalated in the past six months, with an outpouring of opinion pieces on the risks and ethics of a science that is undergoing an exponential period of advance.

One of the key figures in this, as a contributor to both the science and the debate, is Fei-Fei Li, Sequoia Professor of Computer Science at Stanford, and co-director of AI4All, a non-profit organisation promoting diversity and inclusion in the field of AI.

Review: The Worlds I See – Fei-Fei Li (Flatiron Books)

Aside from one controversy during her tenure as Chief Scientist for Google Cloud, involving a proposed partnership between Google and the Pentagon, Li has been something of a role model, not least because of her prominence in an area dominated by alpha-male personalities.

Free of the influence of stylists and image-makers, she comes across in interviews with the fluency of someone who wants to think their way through ideas as they arise, rather than deliver platform statements.

Li describes The Worlds I See as “a double helix memoir”. One thread is the coming-of-age of the science of AI; the other is an account of her own coming-of-age as a scientist. The personal dimension came to the fore, she says, after what was initially a “very nerdy book” was given the thumbs-down by a colleague.

Matter becomes mind

The story begins in Chengdu in China’s Sichuan province. As the only child of a family “in a state of quiet upheaval”, Li had a sense that her elders had been through more than they could tell. Her academically trained maternal grandparents found themselves on the wrong side of history during the Cultural Revolution. Her mother’s intellectual energies were thwarted.

As if there were some braided version of Yin and Yang in her heritage, her father’s free-spirited personality provided a complementary, if antithetical, form of influence. He was, says Li, the kind of parent a child might design for themselves if left to their own devices. He was impulse-driven, possessed of miscellaneous fascinations, which took him on excursions through the rice fields looking for butterflies, stick insects, wild rodents.

Her mother, meanwhile, was determined to escape. This ambition was realised in 1992, when the family moved to the United States. They settled in Parsippany, New Jersey, where 15-year-old Li, grappling with the demands of high school in a foreign language, demonstrated a capacity for long hours of work directed towards the academic goals her mother valued.

Her father’s fascination with natural life forms transferred to the object world of garage sales. He continued to involve Li in the practice of “studying everything in sight”.

Throughout The Worlds I See, Li reflects on the influence of this parental binary on her advancing career as a scientist. Without the fierce intellectual determination of her mother, she could not have persevered with her high school studies, given the family’s ongoing struggle for economic survival. Without her father’s childlike capacity to pay total attention to random phenomena, her research might never have found its innovative path.

The braid of fascination and intellectual drive twists in unexpected ways. It eventually fuses into an almost visionary faith in what Li terms the North Star of her life: a vocation to shift the parameters of understanding by asking “audacious questions” of the kind pursued by the great physicists who inspire her: Albert Einstein, Roger Penrose, Erwin Schrödinger.

Her own audacious question – “what is vision about?” – came into focus by degrees. For someone given to describing her enterprise in terms of revelation and revolution, her actual research on vision seems anything but visionary.

Undergraduate study in physics and computational mathematics at Princeton yielded an opportunity for vacation work as an assistant to a neuroscience team at UC Berkeley. They were attempting to capture the neuronal responses of a cat to visual stimuli. The targeted area of the brain was probed by hairline electrodes to pick up signals.

These signals were translated first into to sound waves, then back to visual patterns from which the team were able to recompose something approximating the original image shown to the animal.

Hardly the stuff of romance, yet Li comments: “Something transcendent happens. Matter somehow becomes mind.”

What is data?

This insight sustains Li through her protracted labours. She becomes convinced that the principle can be applied to machine learning.

Following evidence that visual recognition in the human brain moves from the general to the increasingly specific (bird, water bird, duck, mallard), Li and her postgraduate collaborator set out to feed the computer with a comprehensive range of examples in a limited set of categories.

New image technologies in other domains came to their assistance. Google Street View identified 2,657 models of car on the road in 2014. Amazon Mechanical Turk escalated the scale and speed of their research as categories multiplied, from the original ten to thirty, a hundred, a thousand.

But the project had all the burdens that faced Charles Darwin as he attempted a comprehensive taxonomy of pigeons, or James Murray compiling the Oxford English Dictionary.

For Li, the apparently humdrum conviction that learning should be driven by data rather than algorithms arrives as “a moment of epiphany”. The audacious questions “what is vision?” and “what is intelligence?” merge. They become associated with a third question: “what is data?”

A rapid thaw in the “AI winter” of the first decade of the 21st century commenced in 2012, when research into machine learning made a breakthrough in the direction of “big data”. It was all about scaling up, increasing the retention capacities of AI to incorporate the range and complexity of phenomena in the world itself.

Li found her approach converging with that of Geoffrey Hinton, the Toronto-based cognitive psychologist often credited with spearheading the AI paradigm shift. Data can be exponentially multiplied, Hinton proposed, when machines talk among themselves. Digital agents scan diverse areas of data and exchange what they have learned to generate more sophisticated modes of correlation.

Intelligence comes to be seen not as an inherent property of a machine or a human brain, but as something out there. It arises from interactions between objects, events, beings and environments. There is more of the gatherer than the hunter in its development.

Distributed intelligence

Distributed intelligence means distributed opportunities to participate in the co-evolution of human and machine intelligence. Big science and high technology cease to be the exclusive preserve of specialists whose modes of knowledge are beyond the understanding of ordinary people. Anyone who has had an exchange with Chat GPT on Open AI is contributing.

Li insists, however, that effective human learning requires education. The most important figure in her own education was her high-school maths teacher, Bob Sabella, who kept her on track as she struggled with the English language curriculum. He remained a friend and mentor through every stage of her academic advancement.

It is the dedicated school teacher, Li says, who is the real emblem of the future in human technology. She co-founded AI4All in 2017 with the aim of providing hands-on training for high-school students, especially girls, students of colour and those from immigrant families or low income communities. Li herself fits most of these categories.

The experiences Li recounts in The Worlds I See display an extraordinary capacity for persistence in the face of obstacles. She completed high school while supplementing the family income with a $2 an hour job in a Chinese restaurant. As a graduate student, she was running the family dry-cleaning business.

Her exams at Princeton were done by special arrangement at the hospital clinic where her mother was undergoing surgery for a deteriorating cardiovascular condition.

But it is as if everything she experiences is turned to account in the pursuit of the North Star. Recurring crises in her mother’s health gave her a familiarity with hospitals, which led her to explore how AI might be deployed, not to replace the vital role of human nurses and health workers, but to support them.

If Li’s efforts can be seen as a feminist enterprise, it is perhaps because the field in which she works is dominated by male celebrities, who persist in seeing the future as a Darwinian struggle between human and machine intelligence.

“Which is smarter?” is less an audacious question than one that needs to be consigned to the dustbin of history. Speaking in 2018 to a Congressional hearing on Power and Responsibility in the application of advanced technologies, Li said:

There’s nothing artificial about AI. It’s inspired by people, created by people, and most importantly it has an impact on people.

Explicitly distancing herself from those, like Hinton, who are seeing the current breakthrough in AI potential as an existential crisis, Li is concerned with tangible social risks, and specific ways to address them.

In a recent discussion with former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, now Head of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, Li expressed her belief that policy intervention can install the important safeguards in areas where the impact of AI is likely to be greatest.

These include its benign potential in health and education, as well as the dangers opening up through disinformation, the loss of privacy and the replacement of human work.

If there is an overriding theme in The Worlds I See, it is that human and artificial intelligence form a double helix. How this evolves, and with what consequences, will depend, Li says, on whether we create “a healthy ecosystem” in which talent, technology and public sector participation are co-ordinated.

Jane Goodall, Emeritus Professor, Writing and Society Research Centre, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.