A basic tenet of #Metoo dramas is the pitting of the genders against each other, preferably with as many incendiary remarks fired across the stage as possible. If there’s time, one might add in a splash of intergenerational feminist conflict.

In Melanie Tait’s latest play, “A Broadcast Coup” (playing now at the Ensemble Theatre until 4 March), the central conflict sees one man fight against three women.

Mike King is one of the country’s most lauded radio hosts. He is a Silver Logie winner and has a weekly column in the Saturday newspaper.

He’s the AM version of Alan Jones, or Chris Smith (though Tait has denied the character was based on either). He’s a boganed, local ubermensch. He’s also one of those men on that “Shitty Media Men” list that was doing the rounds a few years ago, collating victims’ allegations of sexual misconduct by men in the media in an attempt to bring them down.

King is about to experience an unexpected coup. Though he has no idea, because he’s just returned from a three week anger management retreat in Fiji, refreshed, ready to get back to work.

He insists he is a changed man. Tony Cogin is convincing in this role.

His latest workplace misdemeanour has been swiftly dealt with by the executive producer of his show, Louise, aka his work wife, played by Sharon Millerchip. She picks up his dry cleaning, makes sure he keeps his appointments, buys his niece’s birthday presents, drops off books he needs to get across before the next day.

She is every woman who has ever been in a relationship with a man, or worked under one — the invisible enabler. The malleable and silent lubricant that keeps the phallic engine running.

But Mike’s easy-going, casual misogyny might need to be reigned in, now that he has a new junior producer on his show: Noa, played by Alex King, is a 24-year old sharp-mouthed, “super woke” Zoomer who “lives feminist theory.”

Thanks to Noa’s instinctual gift of wrenching, she secures King an interview with the country’s most talked about wonderwoman of investigative journalism — podcaster Jez Connell (Amber McMahon), the “slayer of baby boomer bullshit,” who’ll come on King’s show to discuss the merits of podcast over radio.

Naturally, King feels threatened. Connell is a “startup journalist” with her own media company. She produces shows like Slapper – a series about the cosmetics industry and its dark secrets, and her most famous, “A broadcast coup” — which investigates problematic men and tries to hold them accountable for their crimes.

Connell has a simply goal: to make workplaces safe for women.

Now she’s got her eye on her next target: Mike King. A handful of women have already gone on the record. Now, she needs one more to take him down. She has a personal vendetta against him too — having worked as a producer on his show decades ago, before conveniently being shipped off to another network after a violent encounter perpetrated by King.

Which brings me to the final nemesis of King’s — who isn’t actually a woman.

Troy is a Ronald Rule follower, a company man in a managerial position trying to ensure everyone gets at least ten hours rest between shifts. He’s the bureaucratic authoritarian, checking off employees’ induction procedures with the manic precision of a military sniper.

In this role, Ben Gerrard’s comic timing is immaculate. He chews every scene he’s in. I could hardly recognise him as the ultra manicured psychopath of Patrick Bateman, which he played in American Psycho, the musical, in 2021 — so feminised and neutered he becomes in this role.

I suspect Tait wanted us not to see him as a man — so de-masculated he is; his strenuous commitment to yoga is mentioned, as well as his straw-sipping tendency on his drink of choice; the iconic neon orange of an Aperol spritz.

His character is used to reinforce the one-dimensional toxicity of ‘the masculine’ that King represents, reminding us #notallmen, which is really #notallstraightmen — a harder gripe to swallow.

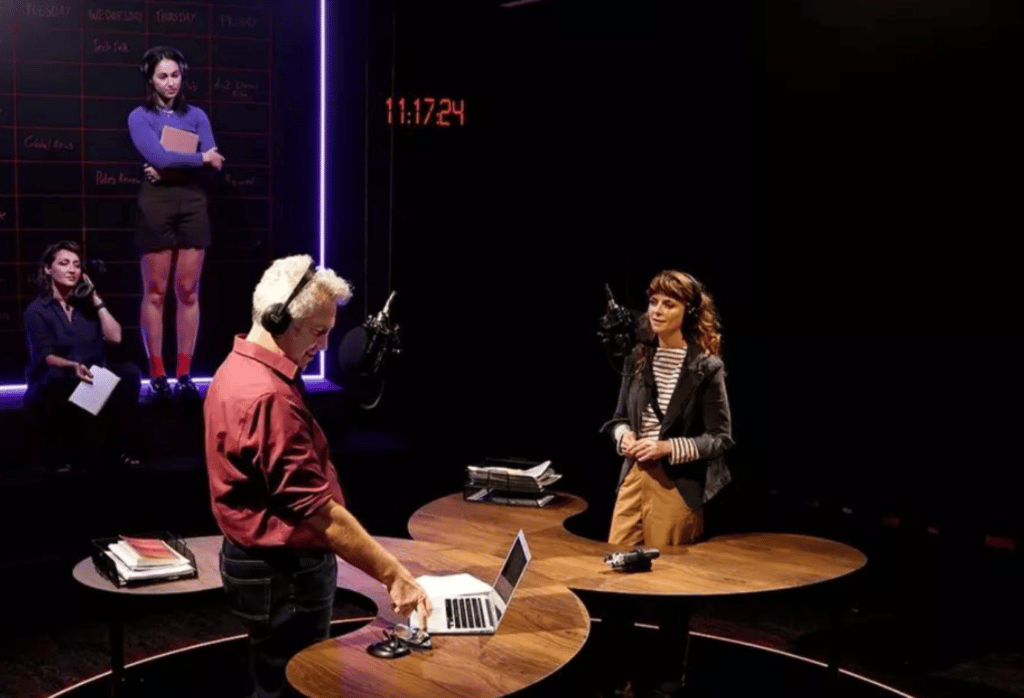

This is a play about radio v podcast, an allegory for male v female, traditional modes of media v the progressive, ‘journalism’ v activism. Under Janine Watson’s direction, these conflicts are fluidly explored from one scene to the next. Veronique Benett’s clever stage design sees a pair of kidney-bean desks create convincing sets depicting a radio-production studio, office, home, bar.

King’s anxieties about his job (therefore his masculinity) are really anxieties about his function as a man, which is fundamentally rooted in misogyny (here, I am reminded of Wesley Yang’s terrific quote: “[There is] no masculinity independent of the domination of women.”

We see King nurse anxieties about his previously unquestioned place in the world, his entitlement to fame and fortune, his absolute lack of accountability for his behaviours and beliefs.

These ideologies leak (so ubiquitous is the patriarchy) that Louise finds herself at loggerheads with her new hire — deciding it’s her duty to tell Noa how to dress to ‘protect yourself and your professionalism’ – Noa wears a blue top that looks like a work-out bra, exposing her midriff.

Ah, how we loathe to see women policing other women!

Louise is a Camille Paglia feminist. Noa is more aligned with Clementine Ford. Whose feminism is correct?

The play doesn’t provide any answers. It is not interested in that question. It is more interested in being funny, than being corrective. What is it ultimately interested in, then, you ask? How do we fix the problem of problematic men?

Tait’s ending might not satisfy our real-world circumstances (taking down one man doesn’t really shift the systemic problems engendering all levels of society) but it’s entertainingly feel-good.

Propelled by the riveting sound design by Clare Hennessy, along with Tait’s sharp, athletic dialogue, this is a dynamic, glittering play.

And though King might have been too arch at times, his character like a bundle of cliches of a ‘problematic man’ and Louise could have been given more depth, more backstory — I left the theatre with a heart filled with admiration and verve. Which is what art should do, no?