Writer Jessica Valenti delivered this devastatingly accurate statement, a riff on the original quote in an article by Thomas Millar, to highlight the way in which legal systems and networks of people work to protect sexual offenders from justice.

Last week, American multimillionaire Jeffrey Epstein was arrested and charged with sex trafficking for crimes committed from 2002 to 2005.

It is alleged that he sexually abused young women and girls as young as 14, who he forced to massage him. In return, Epstein groped, masturbated in front of and used sex toys on them.

He paid the ‘masseuses’ and asked them to bring new recruits, also paying them for introducing new girls into the operation, and then paying the new recruits in an attempt to buy their silence.

Epstein, who was previously convicted in 2007 on two counts of soliciting a minor for prostitution, has long escaped meaningful justice.

For the prostitution charges, Epstein merely served 13 months in a private wing of a county jail. During his sentence he was allowed out for 12 hours, six days a week, to go to work at his Palm Beach office, thanks to a cushy non-prosecution agreement negotiated by his ‘all-star’ legal team.

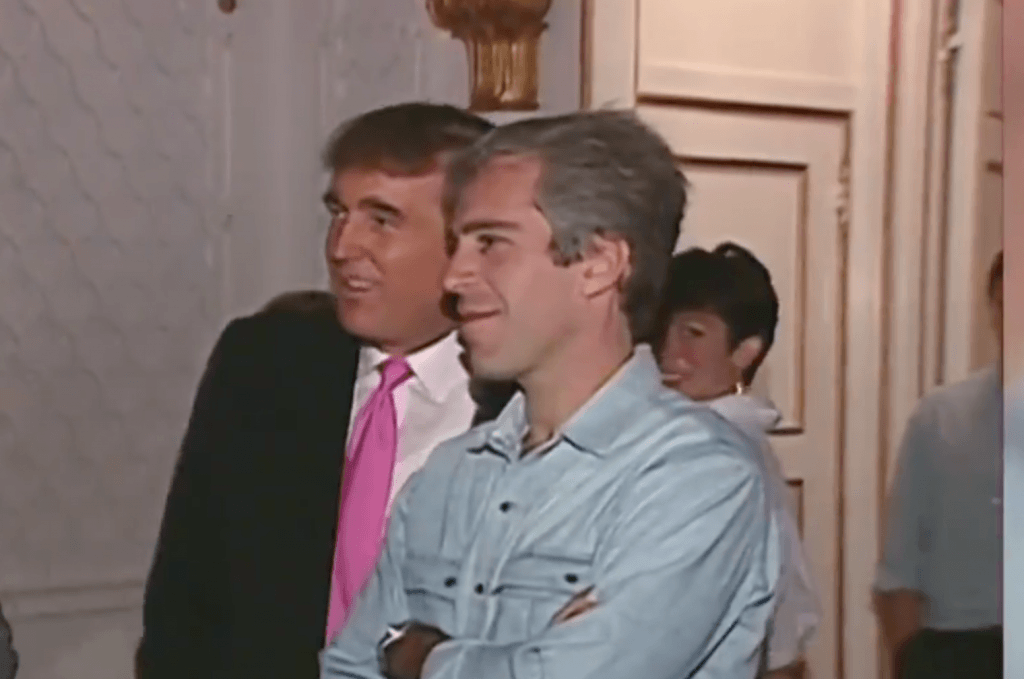

He had high powered and far-ranging connections, including with politicians like former President Bill Clinton and now-President Trump, businessmen Richard Branson and Warren Buffet, media magnates Rupert Murdoch and Michael Bloomberg, and legal experts like Harvard law professor, Alan Dershowitz. (Dershowitz was a member of the all-star legal team.)

He also kept up a reputation of being a philanthropist, once travelling to Africa with Clinton and now-disgraced actor Kevin Spacey to ‘promote AIDS awareness’.

While there is (so far) no connection between Epstein’s crimes and his contacts, his association with people in positions of immense power and credibility and his charity work bolstered his reputation as a ‘good man’.

Wealth, connections and reputation, draconian laws which place a seemingly impossible burden of ‘proof’ on victims, unfounded stereotypes of ‘victims’ and ‘rapists’, and misplaced guilt for the ‘wasted potential’ of offenders allows privileged men get away with rape.

In Queensland and New South Wales, a 110-year old ‘mistake of fact’ law enables would-be rapists to plead not guilty based on their misunderstanding over whether consent was given.

Based on this defence, even concrete evidence can be dismissed. Both states are currently reviewing the legal loophole.

In all jurisdictions around Australia, however, reported rapes versus conviction rates are alarmingly disparate: just 10 per cent of alleged cases result in convictions. But before you even think it, rates of false accusations are very low.

Firstly, around 60 percent of sexual assault incidents go unreported in Australia.

False allegations of rape and sexual assault account for just four per cent of all reported cases in the UK.

The figure remains similarly low in the US and Europe, with estimates ranging from two to six per cent, despite salacious media coverage which may have readers believe otherwise.

Even without the mistake of fact defence, however, the standard of proof required of victims is higher than in other crimes, making it harder to prove a defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

A consequently small number of rape convictions perpetuates the myth that rape is over-reported, undermining the credibility of women as victims.

For men, it’s the opposite. The prevailing stereotype of a rapist is so classist, and typically racist, that many can easily distance themselves from charges.

In research interviews conducted by Jamie L. Small, a sociologist and Assistant Professor at the University of Dayton, respondents consistently stereotyped rapists as ‘lower class men’, including trial attorneys who participated in the interviews.

A person’s likelihood to commit rape or sexual assault has nothing to do with their level of education, race, family upbringing, personal reputation or wealth.

A person’s likelihood to be acquitted or receive an overly lenient sentence for such crimes, however, has everything to do with these factors, because we conflate them with credibility.

In an article for The Washington Post, Monica Hesse argues that the odds of justice in America are ever in favour of powerful men:

“The pathology illustrated in Epstein’s case is the pathology of the American courts — the judicial one and the court of public opinion. It’s the implication that the wealthy deserve less punishment and more benefit of the doubt.”

This is certainly true in the cases of men like Trump – himself credibly accused of sexual assault and harassment 20 times, R. Kelly, Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, and even Brock Turner.

Brock Turner was a student at Stanford in 2015 when he was caught penetrating an unconscious woman with his fingers near a dumpster during a fraternity party.

Sentenced to just six months jail – of which he served three – out of a possible 14 years, the judge presiding over Turner’s trial was unfairly swayed by letters of support from friends and family attesting to Turner’s good character.

Turner’s case was viewed as ‘privilege in action’ because he is white, was a student of a prestigious college, and an athlete.

The 22-year old victim, who remains anonymous, was forced to deal with the consequences of the justice system ‘prioritising men’s potential’ over her ‘lived experiences’, despite even having witnesses who testified to Turner’s guilt.

Deborah Tuerkheimer, a professor at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, says that the impact of sexual violence on victims is routinely overlooked in favour of the impact that potential punishment would have on offenders:

“There’s a longstanding tradition of trivialising harm to victims of sexual assault and focusing instead on harm to perpetrators.”

In the UK, statistics show that this misplaced guilt, particularly for sentencing young offenders, means less than a third of men aged between 18 and 24 prosecuted for rape are convicted.

Journalist Amanda Marcotte writes that rape and sexual assault committed by powerful white men is all-too often trivialised or dismissed because of an ingrained cultural precedent in which their appalling behaviour is treated with leniency:

“It’s slotted into the broad set of behaviours that are indulged as adolescent shenanigans when performed by privileged white men, but viewed as transgressive with anyone else: drinking to excess, gambling, adultery — anything that can be classified as “boys will be boys,” even when said boys are middle-aged men.”