For centuries, the man was a stand in for all people, including women. Men talked with men and wrote the philosophy books that instructed us on how to be a human being. Men wrote plays, music, made laws, created art. The man was the emblem of the human being.

When it comes to research in the biological sciences, men have stood in place for women and it’s hard to believe that only recently have scientists recognised the importance of including women in their studies.

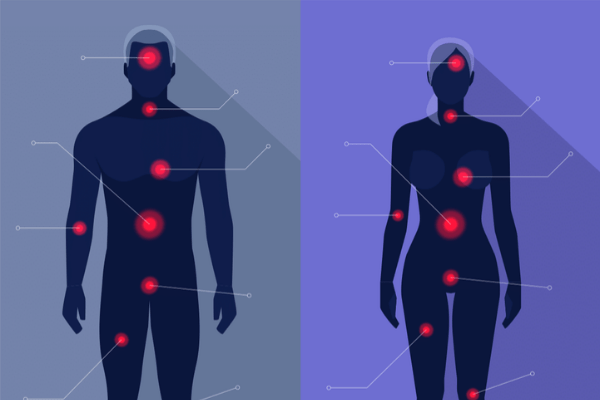

Consequently, we’ve seen huge gaps in our understanding of how diseases, medicine and treatments impact men and women differently.

Just another way, out of the countless ways, women are othered. An afterthought.

Until recently, women were excluded from research because those in charge (men) thought that the fluctuation of female hormones may affect study results.

Nicole Woitowich, along with her team at the Women’s Health Research Institute at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, in Chicago has revisited a study conducted 10 years ago which found females were being excluded from biomedical research based on fears that hormonal variations in women were complicating results.

This, despite the prepossessed idea that hormones skew results has repeatedly been disproved.

Woitowich‘s study was published on the peer-reviewed scientific journal eLife this week, titled “10-year follow-up study of sex inclusion in the biological sciences” .

Her team analysed more than 700 scientific journal articles from nine fields published in 2019 and assessed the degree to which males and females were represented as subjects in research. They evaluated the number of times scientists discussed differences in sex in results and recorded whether scientists gave a reason for single-sex studies or for why they did not analyse data by sex.

Startlingly, her research found that some scientists did not provide an exact number of the males and females studied and that only 4 percent of published papers gave reasons for why they did not use both sexes or did not assess data by sex.

Ignoring sex may lead scientists to make dangerous assumptions about the ways in which certain diseases or medication affect women.

Woitowich, who is associate director of the Women’s Health Research Institute, believes this systemic bias is akin to “trying to put together a puzzle without all the pieces.”

“The implications of not analysing research data by sex are endless,” she told U. S News health reporter Serena Gordon.

“Without this, we have no way of telling if or how new drugs and therapies may work differently in men and women. It hinders progress toward personalised medicine and it also makes it difficult for scientists to repeat studies and build upon prior knowledge.

“When we fail to consider the influences of sex in biomedical research, it’s like we’re trying to put together a puzzle without all the pieces,” Woitowich said. “In order for us to improve our understanding of health and disease, it is essential that we include both sexes in research studies and analyse data accordingly.”

Certain diseases affect more women than men

In the US, two-thirds of people with Alzheimer’s disease are women. In Australia, it’s about 56 per cent and remains the leading cause of death of women in the country. If there’s an over-representation of male subjects in the studies, it means women’s lives are not been taken seriously.

Erin Mulcahy Stein, executive director of Maria Shriver’s Women’s Alzheimer’s Movement in the US, believes it’s important to understand what role sex plays in diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

“Women have at least three or four life stages that men don’t have, such as menstruation, pregnancy and menopause can affect how a disease develops in women,” she said.

“If we don’t have full understanding of these stages because we’ve left out 51% of the population, there’s a real risk there that we might miss something. We’ve seen it in heart disease when women were dropping dead of heart attacks because doctors thought women would have symptoms the same way men did with crushing chest pain, but that’s not how women present with the disease.”

Differences in research and diagnosis are also compromising women suffering from Alzheimer’s. For years, studies found that women performed better on standardised tests used to diagnose Alzheimer’s. As a result, they were being diagnosed later, thereupon increasing their mortality from the disease.

Stein believes organisations like the Maria Shriver Women’s Alzheimer’s Movement are critical in pushing the question front and centre of ‘How could we possibly know as much as we need to know about diseases like Alzheimer’s if women aren’t included in the research?’

“There’s an increased awareness that’s come from the aggressive and unapologetic drumbeat from organisations like ours,” she said.

Ignoring sex differences in studies also ignores the reality that various drugs and medications have different effects on men and women.

Ambien, for instance, and other sleeping pills, are metabolised slower by women. The drowsiness side effect lasts longer, after they take it. After that discovery, the Food and Drug Administration halved the dosage for women, based on these findings.

Last year, a study from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information found that standard therapy for Glioblastoma (GBM), the most common malignant brain tumour, worked better in women than in men who have a specific kind of brain tumour.

The study concluded that “Greater precision in GBM molecular sub-typing can be achieved through sex-specific analyses and that improved outcomes for all patients might be accomplished by tailoring treatment to sex differences in molecular mechanisms.”

Professor Vineet Arora from University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine believes that many male scientists simply may not have the issue of sex while they are conducting their research.

“Given the significant sex differences from biology to behaviour, excluding females means one cannot assume that any findings would apply to females,” she told The Scientist. “Moreover, it is possible that by doing a sex-based analysis, scientific breakthroughs could occur that could be important for all people by understanding how certain interventions vary by sex.”

Woitowich believes disregarding sex in research harms women’s health.

“Sex influences health and disease in multiple organ systems. It’s not just related to the reproductive tract,” she said. “We need this information. Right now, we’re trying to put a puzzle together and we don’t have all the pieces. By including both sexes in research, we can improve the health of all people.”

“It was assumed that there was no difference between males and females outside of the reproductive tract, and it was just easier and cheaper to use one set of animals in research, and those tended to be male. One of the things I found most worrisome was that close to one-third of those who used both males and females didn’t report the numbers of each sex.

“One of the basic tenets of scientific research is that we share our methods so that people can repeat our work and build on it,” she said. “And if we don’t have even the most basic information of, say, this study used 10 mice, five of which were female, five of which were male, I think that’s going to play a huge role in our ability to reproduce studies.”

Associate professor Annaliese Beery from Smith College co-authored the study and said when sex is not used as a variable in the analysis, the opportunities to find effects of the other variables under investigation are missed.

“The results show really promising progress in inclusion of females across disciplines, but also highlight the concerning lack of examination of results by sex,” Beery said. “If sex differences are not examined before males and females are pooled, we miss the opportunity to understand when sex differences are or are not occurring.”

Associate professor Julie Silver at Harvard Medical School told STAT Newsthat variables including body weight, muscle mass, and hormonal variations can determine differences in how male versus female subjects may respond to treatments.

She believes female researchers are more likely to consider aspects of the biological variables than male researchers, and therefore, women should be continuing to publish and research.

“If women are publishing less, sex inclusion is going to take a hit,” she said. A study published last month in Nature found that since the forced closure of labs across the world due to the pandemic, there have been lower submission rates from women to some journals by women.

Kathryn Schubert, president and CEO of the Society for Women’s Health Research in Washington D.C, believes if differences are not being been considered in a study, “it’s almost not worth it.”

“You have to include the other half of the population,” she told U. S News’ health reporter Serena Gordon.

“In order to help make [sex-based research analysis] the norm, not only do universities need to ensure that sex-based research policies are being implemented, researchers need to understand that sex is an important biological variable.”

The future of research

In 2016, a new policy was created by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) requiring scientists to “consider sex as a biological variable” in order to receive NIH grant funding. It aimed at increasing the representation of females as research subjects. And things have improved. In 2009, only 28% had both males and females. In 2019, the number has jumped to 49%.

Woitowich believes a stronger future demands more policy changes to insist on sex- difference to be a mandatory factor in research .

“In this study, the literature was all peer-reviewed,” she said. “Editors of journals need to require information on sex. And, other funders besides the NIH need to make inclusion of both sexes a requirement, or if you’re studying just one sex, explain why. If you are including both sexes, describe why you’re not doing sex-based analysis.”