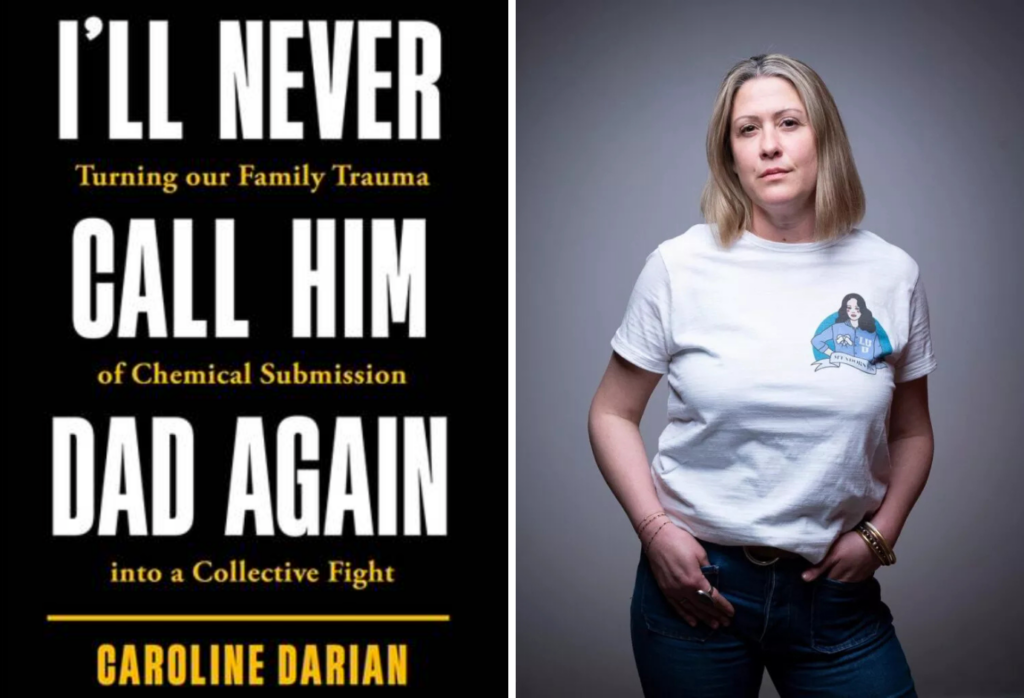

A month after her father was sentenced to 20 years in prison for drugging her mother before inviting dozens of men to rape her, Gisèle Pelicot’s daughter Caroline Darian has published the English edition of her book, I’ll Never Call Him Dad Again.

In it, she recounts the years in her life as she watched her mother exhibit sleepiness, vagueness and early signs of Alzheimer’s without knowing what was going on.

Darian, whose surname comes from combining the first names of two of her three brothers, David and Florian, was a key witness during the trial last year against her father, Dominique Pelicot who was found guilty on December 19 of repeatedly drugging and raping his wife for almost a decade. Fifty other men were convicted of rape, attempted rape or sexual assault.

At 45, Darian, a senior communications manager, now wants to use her role as a close witness of her mother’s unspeakable suffering to cast light on the insidious nature of rape, its prevalence, and the need to fund more research into what she describes as the ‘preferred weapon’ of choice for rapists: “chemical submission” — drug-facilitated sexual violence.

The book has been widely praised, with one journalist calling it “an antidote to doubt, shame and silence”, ”remarkable” and another describing it as a personal account of the first 12 months after the revelations first came to light, illustrating how “trauma expands outwards like a shock wave” through a family.

The book recounts the moment in November 2020 when Darian received a call from her mother, telling her that her father had been arrested and was in police custody. The seizure of his phones, computer and hard drive uncovered thousands of images and videos stretching over a decade showing her father drugging his mother and filming her, unconscious, being raped in her own bed.

Darian has described the moment of discovery as “a cataclysm.”

In her book, she remembers how her father spent most of his free time glued to his computer: “…particularly in the evening, and sometimes long into the night.”

“Immobile on his chair, puffing on an e-cigarette, his attention never wavered from the screen. Not even when the house was overrun by his children and grandchildren.”

She also reflects on her own distress at not knowing the truth behind her mother’s growing sleepiness and vagueness — symptoms of the drug that Dominique Pelicot was administering to his wife without her consent or knowledge. Neurologists were sought and MRI scans conducted. But they found nothing out of the ordinary.

“Mum had a brain scan done all the same, but of course it revealed nothing. Needless to say, it never occurred to us to ask for a drug test,” Darian writes in her book.

She also recounts the harrowing moment when she was confronted with photos of herself, dressed in unfamiliar clothing, in her own bed.

“Did he – I can’t keep the unthinkable at bay – abuse me?” she writes. “It takes some time for me to be able to look directly at the police officers and admit that it is indeed me in the photos. I try to think when they might have been taken. It’s hard to say, but they don’t look recent. Florian asks if he can see the pictures of me. I think he should, because otherwise he might cling to the idea that my father could not possibly have done something so unthinkable. Now we’re both in a state of shock.”

The trauma of such revelation leaves her struggling to sleep at night.

“Even though I’m exhausted, I’m terrified by the thought of sleeping in the violet room that had welcomed me so often before,” she writes. “How many aggressors, intent on raping my mother, had passed through this house? I can’t shake off the fear that one of them might come back in the middle of the night, until Florian brings his mattress and lays it down beside my bed.”

She has since said that she is convinced her father abused and raped her.

“I know that he drugged me, probably for sexual abuse. But I don’t have any evidence,” she told the BBC earlier this week. “And that’s the case for how many victims? They are not believed because there’s no evidence. They’re not listened to, not supported.”

In her book, Darian is also determined to challenge our perception of what a rapist looks like, arguing that drugging most often happens in the home, perpetrated by family members or those we know.

“I have tried, without success, to unearth and understand the true identity of the man who raised me,” she writes. “To this day, I reproach myself with having neither seen nor suspected anything … I’m still haunted by the image of the father I thought I knew. It lingers on, deeply rooted inside me.”

In a recent interview for The Guardian, she explained the “crushing double burden” of being the child of both victim and perpetrator.

The book, which was first released in France in 2022, is also a call to action for more training to be given to health care professionals, doctors and police in how to access toxicological testing for victims.

Darian has been pushing for the term “chemical submission” to be used to describe the ways in which sexual assault perpetrators drug their victims before raping them.

“Regular memory lapses should set alarm bells ringing,” Darian warns in her book. “If it happens to you, tell your doctor and ask for toxicology screening.”

According to her, the crime is not well understood and official statistics are often scarce. She also believes there is a universal lack of support offered to help the victims of the crime, with low rates of diagnosis and a lack of knowledge by health professionals hindering efforts.

“No reliable statistics exist concerning its use. In 2020, the year my father was arrested, nobody was talking about it,” Darian writes. “Chemical submission is present at all levels of society and is deployed against a wide range of victims: women, sometimes men, and even children, babies and the elderly … but who is aware of the risk of being chemically subjugated by a spouse, lover, relative or friend [who is familiar] … with the contents of the family medicine cabinet?”

Since her book was released in France, Darian has founded Stop Chemical Submission: Don’t Put Me Under (#MendorsPas), a movement aimed at raising awareness and support victims of drug-facilitated rape. It is also working to establish systematic training for all professionals concerned.

When the English rights to her book was sold last October, Darian explained one of the reasons she had for writing the book.

“I’ve been determined to rise above this appalling ordeal and transcend it into something more noble and useful for all other victims of chemical submission,” she said.

“Difficult to pinpoint, still poorly identified, rarely diagnosed and therefore badly supported, this social phenomenon affects a wide range of people, from women and sometimes men, to children, infants and the elderly, in all walks of life.”

The book is also a celebration of her mother’s strength, a woman she has called a “hero.”

“On the mornings when anger or despair refused to let me out of bed, Mum was always there to encourage me to get up, get out, to interact with others, to keep life going,” she writes.

If you or someone you know is experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, domestic, family or sexual violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732, text 0458 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au for online chat and video call services.

If you are concerned about your behaviour or use of violence, you can contact the Men’s Referral Service on 1300 766 491 or visit http://www.ntv.org.au.