Whether or not there’s the potential for AI to do good or bad, physicist Cathy Foley believes we need to recognise three main things: 1. We’ve got big problems 2. We have to use every tool in our toolbox and 3. AI is a pathway of fixing these problems.

“One of the things that it’s doing already is helping us be able to detect cancer better,” she said last night on ABC’s Q&A. “It’s able to allow us to absorb very large amounts of data and be able to get some sense out of it.”

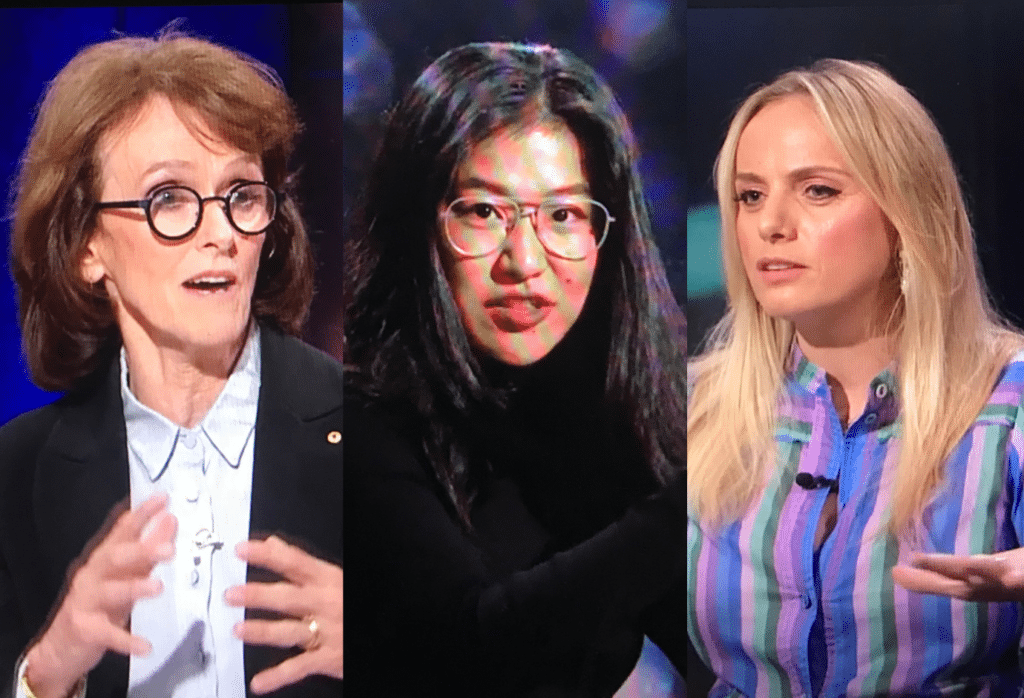

The Chief Scientist of Australia appeared as a panelist on the Monday night show, accompanied by author and journalist Jessie Stephens, Retired Army major general Gus McLachlan, physicist and author Brian Greene, and ThatsMyFace CEO & ethical AI advocate, Nadia Lee, who participated in last week’s Salesforce x Women’s Agenda AI Roundtable.

For Foley, who was elected to the Australian Academy of Science in 2020, the world should see the opportunities that AI brings as something which will make a big difference in the near future.

“We’ve also got to remember that AI is a set of computer programs,” she reminded audiences. “It’s not sentient, it’s not magic. It’s software that’s looking at statistics that goes back and looks at all the data that’s available to it, and then be able to bring out some information based on what it is now.”

When host Patricia Karvelas asked about the risks of AI becoming “smarter than us”, Foley said the only way to ensure that doesn’t happen is to design it in a way where we have guardrails that say: this is where we are agreeing on something and where we don’t agree.

“We’ve done this all the way through humanity when we developed our nuclear weapons, chemical weapons, biological weapons,” she replied. “We created treaties that said around the world, this is how we will operate.”

For Nadia Lee, whose company ThatsMyFace detects malicious content, AI will not spell the end of human civilisation. In fact, she believes that AI will bring amazing things to the human race.

Lee believes that conversations around the ethics of AI must begin with a clear definition between what is deemed “malicious” and what is deemed “non-maclicious.”

“We have to regulate the people, but the technology too,” she said. “If you look at any piece of important piece of technology that’s been developed, it’s always amplified a part of the human race.”

Lee gave the example of social media, which, according to her, has made us more sensitive to what people think of us and how people perceive us.

“But there was always a part of who we were, and maybe AI will amplify other aspects of us in ways that we might not expect,” she said. “When it comes to AI, we are in a place that we can control it and then we can have discussions to put the right guardrails in place.”

Foley is weary of the energy AI expends through its operations, adding that there’s the risk we will use up so much energy on AI that we actually won’t have enough energy in general.

“I think that’s going to be one of the limiting factors,” she said. “You just can’t let things grow forever.”

On the nature of deep fakes

Deep fakes, Lee explained, is the ability to take somebody’s face and replicate it in artificially generated media. She mentioned Open AI’s recently released SORA – “a video virtual version of chat GPT,” Lee explained. “What you’re able to do is put in a prompt and it will spit out something that is actually remarkably lifelike.”

For Lee, when it comes to the ethical usages of deep fakes, we need to distinguish between the good and the bad. According to Lee, an example of a good deep fake would be a video of a recreated memory of her late grandmother, uploaded onto YouTube.

“Do we need to detect that and pull that down? I don’t know. I don’t think so,” she said.

“The problem is when my face is on a malicious piece of content. So let’s say it’s a deep fake porn. Or it’s a deep fake financial extortion scheme or whatever else. That’s where the problem is. So I think what we have to focus on is deciding as a society and for the regulators to define what is malicious, what are the priorities of what is worse and what is better. And how do we detect and mitigate it and moderated it?”

Jessie Stephens believes deep fakes simply erode her trust in everything that she sees. Referencing the recent fiasco with Kate Middleton’s manipulation of a photo, Stephens said such incidents make her not trust institutions.

“I don’t trust what the monarchy tells me,” she said. “I don’t trust what the news is saying. I don’t believe that’s happening unless it’s right in front of me. Is that an issue that if we do start to incorporate deep fakes into the things that we’re seeing?”

Lee, who said she is connected with the some heavyweights in Trust and Safety globally, said the general consensus is that nobody knows what ‘malicious’ is.

“There isn’t a global standard or understanding of what is malicious,” she said. “What is the priority?”

“The Kate Middleton example, do we put in the erosion of public institutions as a priority? Do all the doctored images, any doctored images of any public figure, go into the bucket of content that needs to be detected and moderated?”

AI bias and prejudices

At the moment, AI is very biased, according to Cathy Foley. She gave the example of the use of AI in job applications, screening a certain group of people and excluding them based on gender or culture because they don’t fit the algorithm that’s been used.

“A lot of the work and the development has been done by a very narrow group of population, usually people who are males in Silicon Valley,” she explained. “If we are having a limited group of people actually looking at developing this technology, we’re going to have a very limited technology that comes from that.”

Foley believes what we need to be doing is making sure that the development of technology brings in the full human potential — “so that we get a bit of everything in there and hopefully, live up to that opportunity.”

On regulation

“Any government will want to make sure they are able to control the data that and protect themselves from cyber security,” Foley said, addressing the issue of how Australia will regulate AI.

“That’s really a critical baseline that you would want all governments to be making sure that your information is safe – that our governments have a lot of information that you do not want necessarily be hacked in any way.”

For Lee, she believes Australia needs to collaborate with global entities to get a better feel for what the problem is.

“How can we have a risk based regulation without knowing what the problem is?” she questioned. “Getting access to that data will be really important. And then defining what is malicious and in what way. The key question here also is priority.”

Lee recounted a recent conversation with a colleague who attended the UK Trust and Safety Summit in London.

“What he said was that the consensus out of all the conversations is that everybody now feels the imperative need to stop doing the right thing because otherwise they might get kicked out.”

“I think we need to start looking at regulation as another area of innovation, not a limitation on tech companies…and actually allow them to develop in the right direction that they need to go.”