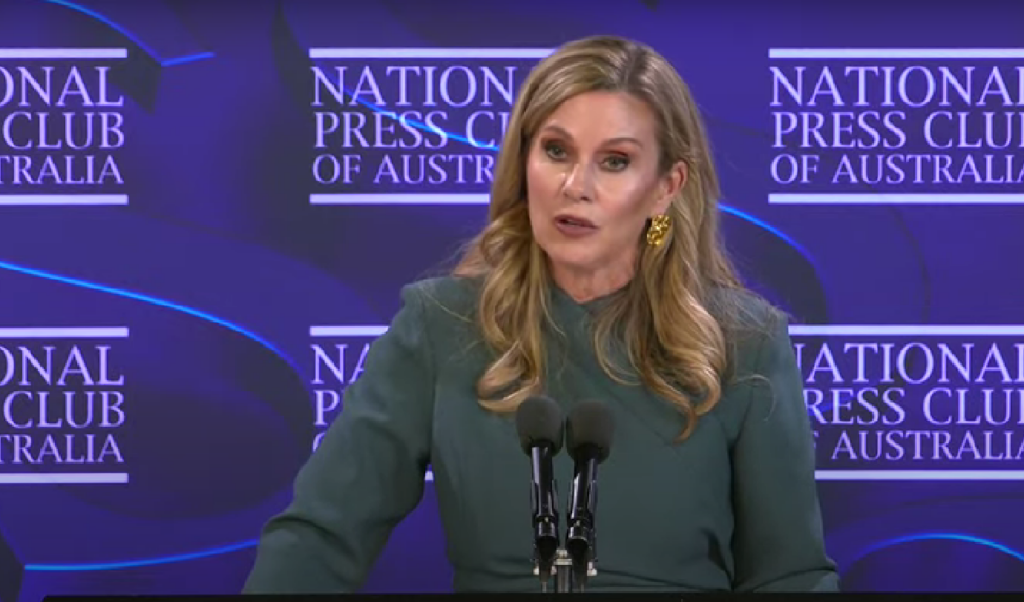

eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant says the upcoming under-16s social media ban is not designed to cut kids off from their “digital lifelines” but acknowledged it was the most “complex” piece of legislation the online regulator has been tasked with implementing.

Speaking at the National Press Club on Tuesday, Inman Grant said the ban wasn’t a “silver bullet” but it would create some “friction” in a system where there has previously been close to no protection for children.

Inman Grant said she didn’t like the term “ban” and instead referred to it as a social media “delay” for children aged 16 and under.

“We are seeking to protect under 16s from those unseen, yet powerful forces in the form of harmful and deceptive design features that are currently engaging their usage online,” she said.

“For that reason, it may be more accurate to frame this as a social media delay – giving children a reprieve from the pervasive pull of platforms engineered to keep them digitally entrenched.”

Inman Grant said the legislation, due to be implemented in Decemebr this year, was largely focused on creating normative change for parents.

“It’s a constant challenge for parents to juggle the urge to deny access to services they fear are harmful to their kids with the anxiety of leaving the kids feeling socially excluded,” she said.

“I can speak from lived experience with three teenagers that this sometimes feels like very effective reverse peer pressure.”

She said there is no doubt the changes to social media access for under 16s will have flaws, especially considering the rate of technological advancement.

“No bill is going to be created that doesn’t have flaws or doesn’t anticipate technology moving 20 times faster. Probably 20 million times faster than any legislation can,” she said.

“I see what we’re doing as protecting Australian voices online because it is those who are most vulnerable that tend to be targeted online and we don’t take action unless there’s an Australian on the other end that’s experiencing hurt and harm at a considerable level.”

Inman Grant’s speech comes after she provided advice to Communications Minister Anika Wells that YouTube should not be exempt from the ban. YouTube has since hit back at the advice, saying: “eSafety’s advice ignores Australian families, teachers, broad community sentiment and the government’s own decision.”

At the National Press Club, Inman Grant said: “When the decision was made by the Albanese government, they didn’t have the benefit of our insights, of our youth research, of the insights that we gained through our basic online safety expectations, transparent reports, our regulatory insights and reports.”

“Any platform that says they’re absolutely safe is absolutely spinning words.”

Inman Grant said the implementation of the legislation was not designed to cut off kids from their “digital lifelines” or inhibit their ability to connect and communicate.

“Far from it. There will be no penalties for those underage children who gain access to an age-restricted social media platform, or their parents or carers who may enable this early access,” she said.

“The responsibility lies with the platforms themselves and there’s heavy penalties for companies who fail to take reasonable steps to prevent underage account holders on to their services.”

“Ultimately, this world leading legislation seeks to shift the burden of reducing harm away from parents and carers and back home to the companies themselves, the companies who run these platforms and profit for Australian children. We are treating big tech like the extractive industry it has become. Australia is legitimately asking companies to provide the life jackets and the safety guardrails that we expect from almost every other consumer facing industry.”

Asked about the unintended consequences of the social media ban, especially for marginalised groups of young people who use social media to build community, Inman Grant said it’s not a total prohibition of children using technology.

“I raised concerns about this when legislation was being deliberated, because we know from research with CALD communities, with communities of disability or ability, with LGBTQI plus folks, that they feel more themselves online than they do in the real world, and they can find a tribe. That’s precisely why I was clear in saying we’re not trying to cut lifelines or to prevent them from communicating, exploring and creating,” she said.

“We’ll see what the final rules look like. But in the initial draft, of course, some of the platforms and services that were exempted are in the form of messaging and online gaming services, where communities can be formed and where kids are using now. And the simple fact of the matter is, adults are probably using social media sites more than kids are today. And so I think we can do both.”