Days after Brian Earl Johnston allegedly murdered his partner, Kelly Wilkinson, his lawyers told reporters: “Obviously, no one expected this to happen.”

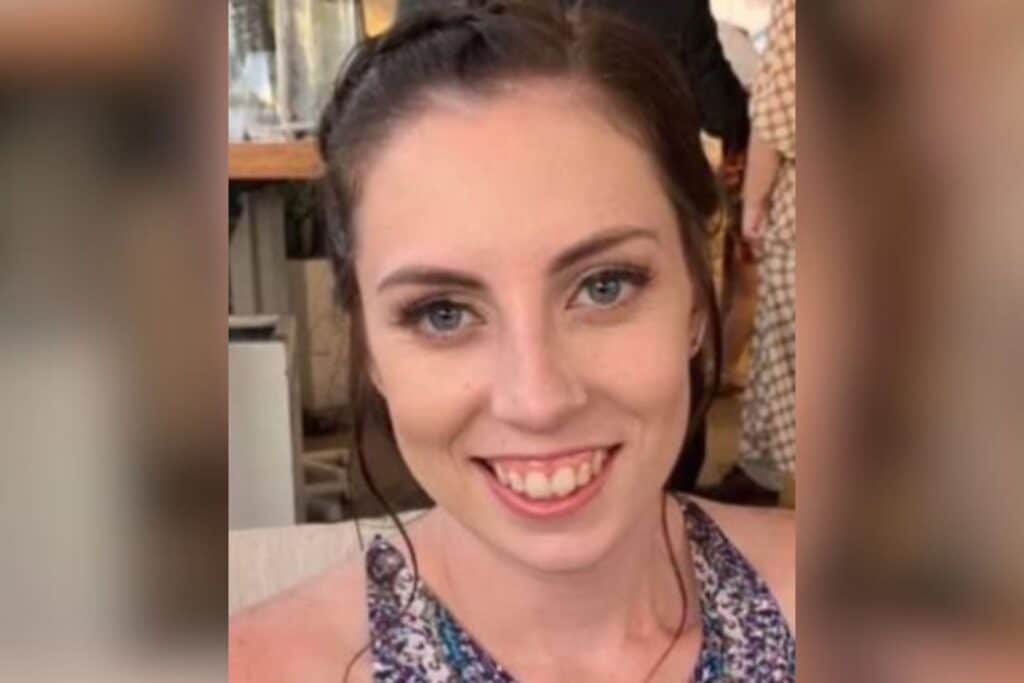

Two years on from 27-year-old Kelly Wilkinson’s death, we now know police could have, and in fact should have seen it coming – had they taken her seriously.

An investigation from Guardian Australia shows this wasn’t the case. With her partner charged with four serious domestic violence offences and given watch house bail, Wilkinson was going to different police stations along the Gold Coast in April 2021 “almost every day”, according to reports.

Her concerns, however, were diminished to an undermining, reductive term: “cop shopping”.

This is how police viewed a woman telling authorities she and her children were not safe in her own home, according to notes uncovered by Guardian Australia. They dismissed her. They didn’t believe her.

Ignored by the system, on 20 April 2021, Brian Johnston tied Kelly Wilkinson to a clothesline and set her on fire.

Ignored by the system, the life of a mother, sister, daughter and friend was cruelly, brutally taken at the hands of her husband.

Police were aware of Johnston. They knew of his four serious domestic violence charges. Day after day, the victim was alerting police of the danger she and her children were in.

Still, according to Johnston’s lawyer, who could have seen this coming?

Domestic violence in Queensland

“I am scared for my life. I am scared for my children’s lives. We are not safe.”

This is what Kelly Wilkinson was telling police in the days leading up to her alleged murder, according to her sister Danielle Carroll.

It was later found that a similar case of a domestic violence-related homicide, the killing of Doreen Langham, was met with “so many inadequacies” and her complaints were “not properly investigated”, according to Guardian Australia.

The danger these women faced could not have been clearer for police, yet their cries for help still fell on deaf ears. Why?

Queensland police have already conceded to the “failure” that is Wilkinson’s preventable death. Brian Codd, the Queensland police assistant commissioner in charge of domestic violence responses at the time of her alleged murder, said it was a “systematic failure” that contributed to Wilkinson’s death.

But her alleged murder isn’t reflective of a “systematic failure” – it’s reflective of a failed system.

The rate of homicides from family and domestic violence in Queensland is increasing at an alarming rate. According to police data, domestic and family violence-related homicides in Queensland have risen by 50 per cent in a year.

In the last financial year, 24 people were allegedly murdered by intimate partners or family members, compared to 16 the previous year. About a third of the alleged killers were known to police.

According to police data, over a hundred police roles specific to domestic and family violence are yet to be filled across the state. Christopher Jory, the current Queensland Police Assistant Commissioner for Domestic and Family Violence, said the police service plans to spend the next two years recruiting 114 specialist officers to fill these roles and help staff vulnerable persons units.

The response, following the inquiry and the 78 recommendations that came from it, is well overdue and is urgently needed. Just last week, a man in Queensland was charged with murdering his wife in Woodhill by running her over with a tractor.

Of course, filling gaps in staff and resources within the Queensland police service will ultimately help the cause of ending violence against women and children.

But what Guardian Australia’s investigation into the 2021 alleged murder of Kelly Wilkinson shows is the response must go beyond the numbers.

When police reduce a woman’s concerns for her safety to “cop shopping”, what this shows is a complete lack of empathy towards women, and a lack of understanding on the issue of family and domestic violence.

Better training for staff in the space of domestic violence is urgently needed not just in Queensland, but around the country. Last year, 63 women were killed by family and domestic violence, according to Destroy the Joint’s Counting Dead Women.

Police in Australia and around the world have a poor track record when it comes to listening to the concerns of women’s safety, and women are paying the ultimate price for it.

Queensland, and indeed Australia, must do better for women. Because if police don’t expect domestic violence-related murders to happen, as Johnston’s lawyer indicated at the time, what hope do we have?