It just seemed a little too heavy and depressing, and maybe even a little risky for some irrational reason, to delve into a book about how people cope with sudden tragedy, and move on following the worst day of their lives.

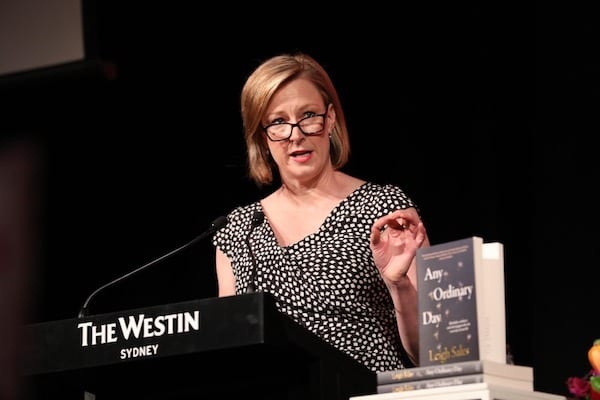

But ten minutes into hearing Sales speak at a Business Chicks event in Sydney, I had changed my mind. I realised the fears I had about reading Any Ordinary Day may have actually been similar to some of the fears Sales had herself when researching it, and interviewing people who had experienced the worst moments of their lives in the full media spotlight.

What Sales shared today was sometimes challenging, especially as she spoke candidly about her own medical emergency following the birth of her second son in 2014, but it was also comforting to hear that people do go on. Resilience gets them through.

“I now feel more at ease with the things I can’t control, that I probably would be able to muddle on by relying on my resilience and the help of others,” Sales said on what she learnt from some of the interviews she did, including with Stuart Diver who lost his first wife Sally during the Thredbo disaster in 1997, and his second wife Rosanna to breast cancer, and Walter Mikac, who lost his wife and two daughters during the Port Arthur massacre in 1996.

“I thought these tragic stories would crush me under their weight, instead they have given me so much hope,” Sales said. “What people can get through is amazing.”

Sales said she lost her sense of security in the world following her 2014 medical emergency when she suffered a uterine rupture while eight months pregnant. She recalled hearing a nurse saying the baby’s heart beat had stopped and then being wheeled into surgery. She woke with tubes everywhere, and her baby in the neonatal care unit with a possible brain injury (he’s now fine and the “boss of the house”).

It’s a similar sense of unease and insecurity that can see some people ignoring the news. Encountering stories of death and disaster in the media, challenge us to reconsider how we perceive fate, and the small choices we make that can result in catastrophic consequences is deeply uncomfortable: like the decision to get a hot chocolate from the Lindt Cafe in Sydney, that Katrina Dawson made in November 2014.

“If the universe or fate, or God, or whatever you want to call it, didn’t give them the courtesy of knowing what was going to happen, it’s unlikely to give it to us either,” Sales said. “We make choices every day without pause, blessedly oblivious to where they might lead.”

Sales spoke this morning about resilience and hope, and shared plenty of research and stats around why we feel “high dread risk” around the chance of a statistically unlikely event occurring like a terrorist attack, but can be more comfortable with “low dread risk” — more ordinary things that happen to people, that can result in the same outcome (death) and are statistically much more likely to occur.

“If the chance of an awful, random disaster affecting us is so remote, why are we so rattled by them?” Sales said, going on to ask why we often think “that could have been me” when random, tragic events affect Australians.

“We hate to feel vulnerable, so we seek reassurance in whatever ways we can. We read horoscopes, pray to Gods, scour the news to see our chances of getting some disease.

Tragedy, if it hasn’t already, will come for all of us eventually. We can’t predict what will happen, or where our choices will lead. But there’s hope in learning about the experience of others.

I will be reading this book.

Read more on Leigh Sales, including her life lessons shared at an International Women’s Day event.