Unlike previous recessions, women, especially those aged 15-24, are over-represented in the hardest hit industries, and have been harder hit than men, writes Jeff Borland, from University of Melbourne in this piece republished from The Conversation.

When a recession hits, no group of workers is immune. But some are harder hit than others. The latest labour market figures are giving us a good idea of who is being hardest hit this time.

So far, this COVID-19 recession is hitting hardest workers with lower earnings. In fact, workers in occupations in the lowest 30% of weekly earnings account for 60% of the decrease in hours worked from February to May.

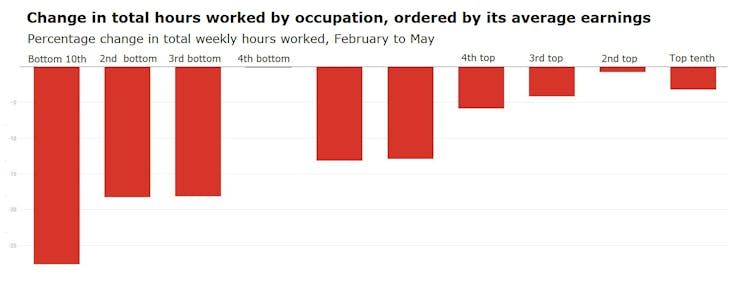

The link between a worker’s earnings and how they are being affected can be seen in the chart below. It shows changes in hours worked when workers are split into ten groups based on the average weekly earnings of their occupation.

It shows that whereas workers in the bottom tenth of earnings had total hours cut by 27%, workers in the top tenth had them cut by only 5%.

What is driving the changes is well understood. Government-mandated business closures and COVID-19 induced changes to consumer spending have cut the demand for labour, and the cuts has been concentrated in a small set of industries.

Young victims, low-paid victims

Compared to a year ago, employment in the accommodation and food services, arts and recreation services and retail trade industries has fallen by about 430,000 – accounting for two-thirds of all the jobs lost.

It follows that workers who were employed in those three industries have been hit the hardest. Many of them are low-paid, but what is also notable is that they are disproportionately young (aged 15 to 24 years) and female.

Young people account for one in two of the jobs lost in in accommodation and food services, arts and recreation services and retail trade.

This means the impact on young people in those three industries explains one third of the total decline in employment.

And female victims

In previous recessions the jobs that have been lost have been overwhelmingly male, many of them taken from the male strongholds of manufacturing and construction.

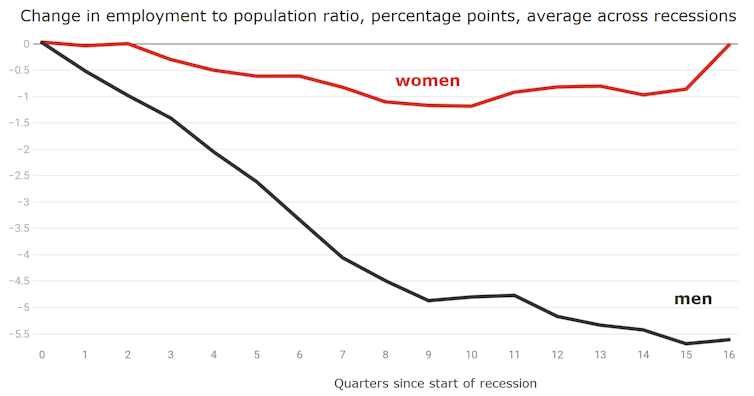

This chart tracks the job losses for men and women in what until now has been the typical recession. It’s the average of job losses in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s recessions.

On average the proportion of women in work hasn’t fallen by much and has bounced back quickly. By contract, the proportion of men in work has collapsed and recovered only slowly.

Not this time. Because women are over-represented in the hardest hit industries, they have been harder hit than men.

Read more: Which jobs are most at risk from the coronavirus shutdown?

While total monthly hours worked by men fell by 7.7% between March and May, total monthly hours worked by women fell 12%.

Understanding where the recession is hitting has important implications, all the more so if renewed lockdowns make it last longer.

While many of the businesses that are closing will eventually reopen, not all of the lost jobs will be restored.

Read more: The next employment challenge from coronavirus: how to help the young

This means support needs to be directed to the victims of this new different type of recession, rather than the victims of typical ones.

Bringing out the old playbook, supporting the industries that are usually hurt, won’t be good enough.

Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.