In recent weeks, Australian universities’ commitment to teaching Australian literature has come under scrutiny. This came amid revelations Sydney University has withdrawn funding from its Chair of Australian Literature – the nation’s first.

Later news of the possible closure of UWA Publishing compounded anxiety about the future of Australian literary studies. An article in The Australian newspaper noted there is no local university in which an undergraduate student can specialise in Australian literature.

Read more:

The open access shift at UWA Publishing is an experiment doomed to fail

The concern goes beyond tertiary studies. We conducted a project exploring secondary school teachers’ engagement with Australian texts. We found Australian books are not consistently taught in classrooms and, when they are, they more often than not marginalise female, refugee and Indigenous authors.

Wikimedia commons

The demographic of Australian classrooms has changed significantly in the past fifty years. But the texts studied in English have remained remarkably stable.

In our multi-cultural society, where compulsory schooling is intended to help develop critically informed and empathetic citizens, this situation requires serious attention.

Why teachers don’t teach Aussie books

Studying English and literature in settler societies was historically intended to support students to value “Englishness”. As a result, Australian literature, if it was acknowledged at all, was systematically marginalised and maligned in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the 1940s – in a precursor to what we now call the “cultural cringe” – an English professor famously renounced Australian literature. He said that, in the absence of appropriate books by Australians, he would lecture on DH Lawrence’s novel, Kangaroo.

Read more:

‘Australia has no culture’: changing the mindset of the cringe

Australia’s first national curriculum, in 2008, attempted to respond to this enduring imperial literary legacy. It mandated teaching Australian literature, placing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander literature at the heart of this commitment.

Wikimedia commons

Most states and territories have mandated text lists for school senior years, which generally include titles by Indigenous authors. But recent research in Victoria has shown school uptake of these texts is limited.

Our research shows teachers are often reluctant to select books by Australian authors. Reasons for this include a limited knowledge of diverse Australian texts, often due to a lack of exposure to Australian literature at school and university.

There are fewer teaching resources for Australian literature too and teachers are concerned about inaccurately representing the stories of Indigenous Australians.

Some teachers we spoke to also raised questions about the quality of Australian literature, as compared with more established canonical texts. One teacher said:

While I appreciate that it is important to have Australian literature in the curriculum […] I find that Australian texts are often very similar and this limits the number of themes and ideas the students are exposed to over the course of their education.

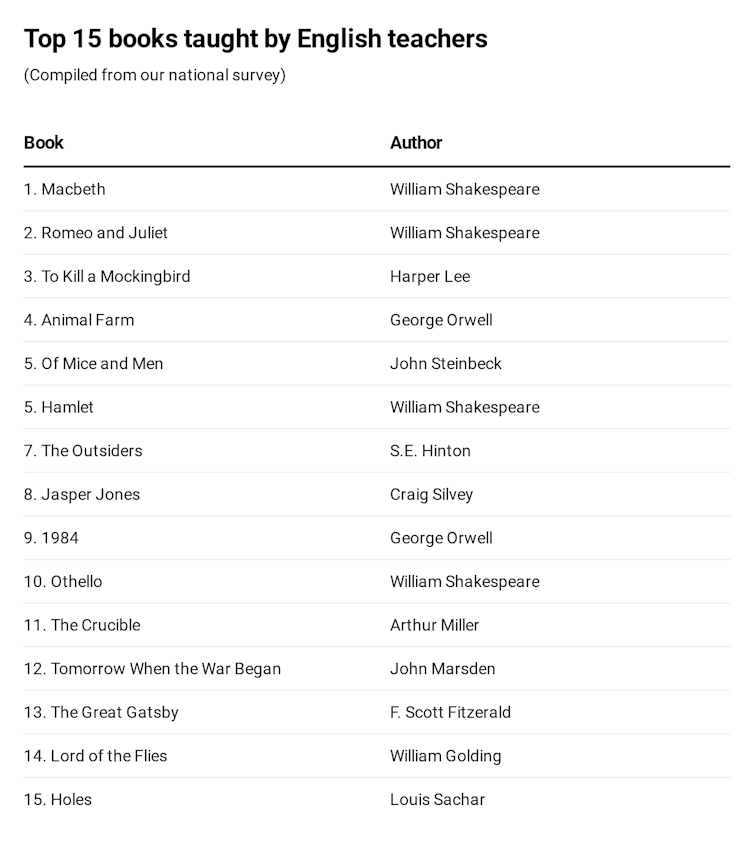

We also conducted a national survey of more than 700 English teachers, asking them what books they taught in class. The following top 15 texts were most referenced:

This should not be seen as a definitive list of texts most used in Australian classrooms. But it does offer insight into the relative status of Australian literature in the curriculum.

Most works on this list are written in the past, by male British or American writers. Most of these have formed part of the school literary canon for generations. There are only two texts by women, Hinton and Lee, and no texts by Australian women, migrant Australians or Aboriginal writers.

Read more:

Diversity, the Stella Count and the whiteness of Australian publishing

The only texts by Australians cited here are Marsden’s 1990s dystopian invasion series and Silvey’s 2009 coming of age novel.

How do we change it?

Our research showed teachers need more time, knowledge, resources and confidence to include more Australian literature in the classroom. This is not surprising given teachers we surveyed and interviewed often completed both secondary and tertiary studies in English without significant experiences of Australian literature.

In response, colleagues and I have partnered with the Stella Prize (a literary award for Australian women writers) to develop the teacher-researchers project.

Teachers select a text from the Stella long-list. They then work intensively with the project team – which includes teacher-educators and Australian literary studies experts – and university archives or other cultural collections, to develop resources to teach their chosen texts that can be shared.

Texts in this pilot project have included Heat and Light by Ellen Van Neervan, Terra Nullius by Claire G. Coleman and The Hate Race by Maxine Beneba Clarke.

This project will expand the literary knowledge and experiences of teachers, students and school communities involved. But a concerted, bipartisan and enduring commitment to resourcing scholarship and teaching of Australian writing across universities and schools is imperative.

If we are to ensure all students experience Australian stories from the past and the present, Australian writing, in all its rich diversity, must be a central part of a literary education.

Larissa McLean Davies, Associate Professor Language and Literacy Education, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.