There is an economic case for the government to invest more in child care to help rebuild the economy after the health crisis is over, writes Danielle Wood, Grattan Institute; Kate Griffiths, Grattan Institute, and Owain Emslie, Grattan Institute in this article republished from The Conversation.

The Australian government’s COVID-19 rescue package for the child-care sector provides a lifeline for centres and parents alike.

Child-care centres now have a guaranteed stream of income and support for wage costs, helping them to stay in business through the crisis. For working parents, there’s the relief child care will be available through the crisis and beyond. Better yet, the care is free.

Read more: Morrison has rescued childcare from COVID-19 collapse – but the details are still murky

But what happens after the shutdown is over?

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has emphasised this is a temporary measure, set to run for six months. But parents, having tasted life free of child-care costs, won’t resume paying without a fight.

There is also an economic case for the government to invest more in child care to help rebuild the economy after the health crisis is over.

Australian child-care costs are high

Out-of-pocket child-care costs in Australia have been relatively high by international standards.

The standing Commonwealth Child Care Subsidy is means-tested. Even for a family getting the maximum subsidy (85% of costs for households with income less than A$68,000) it costs about A$9,000 a year to have two children in full-time care. For a family where each parent earns A$80,000, the cost is about A$26,000 a year.

Full-time net child-care costs absorb about a quarter of household income for an average-earning couple with two young children in Australia. The OECD average is 11%. Almost half of Australian parents with children under five say they struggle with the cost.

Deterring workforce participation

The high cost of child care doesn’t just drain family incomes. It has a big impact on workforce participation, particularly for women.

Women are more likely to be a family’s “second earner”, reducing their paid work hours to accommodate caring responsibilities. For many, child-care costs interact with other elements of Australia’s tax and benefit system to make extra hours of paid work financially unattractive.

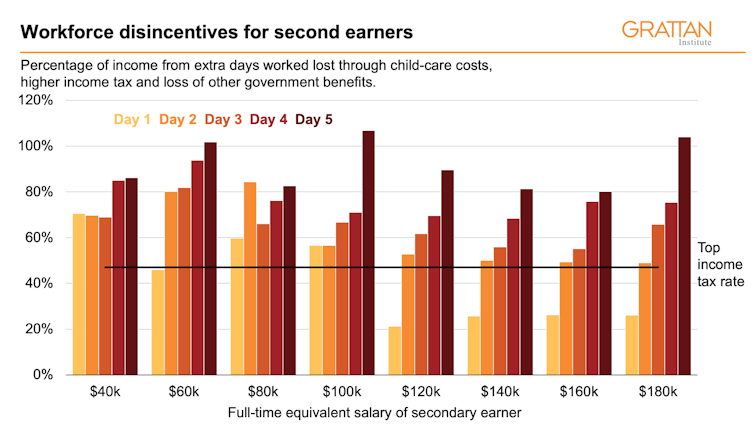

The chart below shows the “workforce disincentive rate” – the proportion of income from an extra day’s work lost through higher taxes, reduced family payments and child-care costs – for second earners. The disincentive rates are high across the board, but particularly punishing for second earners thinking of taking on a fourth or fifth day of paid work.

For example, consider a household with two young children where both parents would earn A$60,000 a year if they worked full-time. Dad works full-time and mum three days a week.

If mum decided to take on an extra day, she would lose more than 90% of the income for that fourth day in child-care costs, tax and reduced family payments. For comparison, someone earning more than A$180,000 and paying the top marginal tax rate (shown by the black line in the graph) only loses about 47% of additional income.

That leaves mum working for about A$2 an hour on her fourth day; and for nothing on her fifth day.

Is it any wonder the “1.5 earner model” – where dad works full-time and mum part-time – has become the norm in Australia?

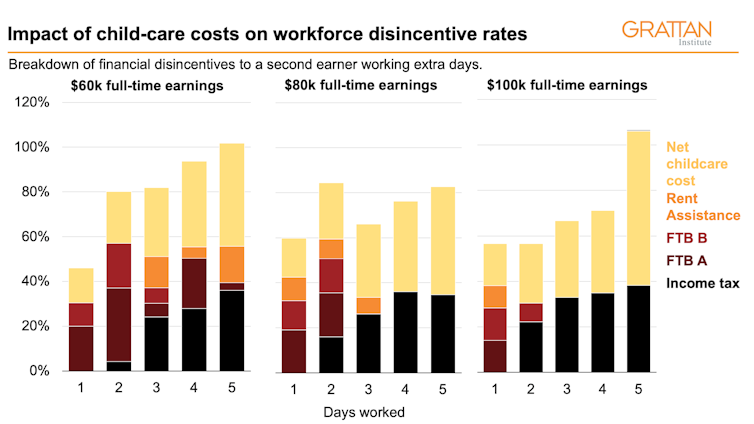

The following graph shows the cost of child care is the biggest contributor to these high workforce disincentive rates. Reducing that cost would do more than any other policy change to boost workforce participation for mothers of young children.

But ‘free’ child care doesn’t come cheap

The Child Care Subsidy cost the federal government A$8 billion last financial year. Making child care free would almost triple that cost. In fact, it could be higher, since free child care would trigger a jump in demand, including by those not in the paid workforce.

There is an attractive simplicity to universal child care, and it would likely lead to a big economic payoff in workforce participation, at least over the medium term (5-10 years).

But scrapping means-testing completely would be a radical change to the system and potentially raise concerns about fairness. Under a universal scheme, all parents of young children would be able to access more than $25,000 in subsidies for each child. This would be true even for high-income parents who currently receive no Child Care Subsidy.

A cheaper and less radical alternative would be raising and simplifying the Child Care Subsidy to reduce the disincentives to work.

Our modelling suggests a subsidy of 95% of child-care costs for low-income families, tapering down slowly to zero as family income increases, would cost taxpayers an additional A$5 billion a year, compared with at least A$14 billion more for a universal scheme.

It would enable many women who want to increase their paid work to do so, support the post-crisis recovery and boost GDP by about $A11 billion a year in the medium term through higher workforce participation.

For policymakers seeking high-return government initiatives to boost the economy, this is an opportunity too good to miss.

Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute; Kate Griffiths, Fellow, Grattan Institute, and Owain Emslie, Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.