Roald Dahl’s books have been edited and rewritten to erase language deemed offensive in today’s social English vernacular.

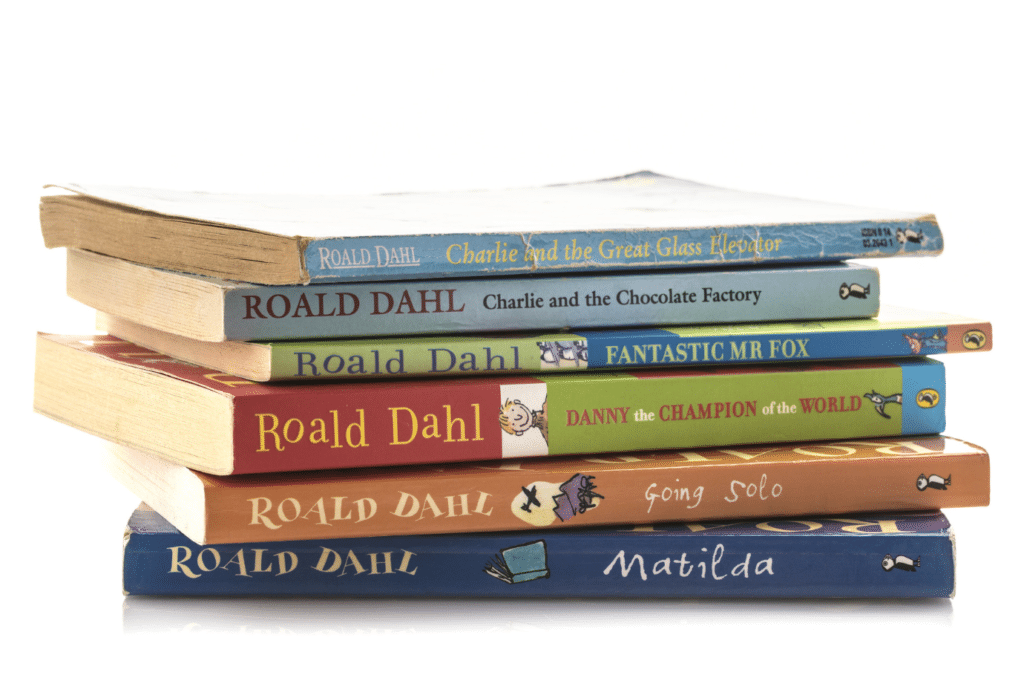

The publisher of Dahl’s works, including Matilda, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, and The Witches announced over the weekend that they have hired sensitivity readers to remove some words and rewrite some text in the UK editions to ensure the books “can continue to be enjoyed by all today.”

So what are the changes?

Descriptions of characters’ physical appearances have been changed, including the removal of words such as “fat”, “ugly” and “black.”

The Telegraph compared new editions of Dahl’s books to past editions, and found that in The Twits, Mrs Twit is no longer “ugly and beastly” but simply, “beastly”.

In James and the Giant Peach, originally published in 1961, the Centipede chants: “Aunt Sponge was terrifically fat / And tremendously flabby at that,” and, “Aunt Spiker was thin as a wire / And dry as a bone, only drier.”

These lines have now been removed and replaced with: “Aunt Sponge was a nasty old brute / And deserved to be squashed by the fruit,” and, “Aunt Spiker was much of the same / And deserves half of the blame.”

Subtler changes have also been made, such as the removal of the word “fat” in the lines: “The fat shopkeeper shouted” has become “the shopkeeper shouted,” and “the fat shopkeeper said” has become “the shopkeeper said.”

Gendered terms have also been neutralised, such as the term “Cloud-Men”, which has become “Cloud-People.” References to “boys and girls” have been changed to “children,” while “mothers and fathers,” has been changed to “parents.”

The term “female” has also been altered.

In Matilda, published in 1988, Miss Trunchbull was originally described as “most formidable female”. She is now described as a “most formidable woman”.

Her “great horsey face” has been changed to “face,” and “eight nutty little idiots” has become “eight nutty little boys”.

In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, published in 1964, an original line read: “The man behind the counter looked fat and well-fed. He had big lips and fat cheeks and a very fat neck.”

The new editions have entirely erased these lines. Other lines that describe fatness, including “The fat around his neck bulged out all around the top of his collar like a rubber ring”; “Who’s the big fat boy?”; and “Enormous, isn’t he?” have all been removed, though Augustus Gloop is now described as “enormous” instead of “fat”. Oompa Loompas, previously described as “small men”, are now “small people”.

In The Witches, first published in 1983, an additional sentence has been added to a description about the witches and their wigs: “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.”

“Fat little brown mouse” has been changed to “little brown mouse” and a line regarding a boy needing to “go on a diet” has been removed.

Official reasons:

Puffin and the Roald Dahl Story Company, which owns the books, made the changes in conjunction with Inclusive Minds, an organisation founded ten years ago that aims to promote equality, diversity, inclusion and accessibility in children’s books.

Alexandra Strick, a co-founder of Inclusive Minds, told The Guardian they “aim to ensure authentic representation, by working closely with the book world and with those who have lived experience of any facet of diversity”.

The Roald Dahl Story Co. which was acquired by Netflix in September 2021, released a statement, saying they seek to “ensure that Roald Dahl’s wonderful stories and characters continue to be enjoyed by all children today.”

“When publishing new print runs of books written years ago, it’s not unusual to review the language used alongside updating other details including a book’s cover and page layout,” the statement read.

“Our guiding principle throughout has been to maintain the storylines, characters, and the irreverence and sharp-edged spirit of the original text. Any changes made have been small and carefully considered.”

The LA Times cited an email from Roald Dahl Story Co. spokesman Rick Behari where he explained, “the overall changes are small both in terms of actual edits which have been made and also in terms of the overall percentage of texts which has been changed.”

“As part of our process to review the language used we worked in partnership with Inclusive Minds, a collective for people who are passionate about inclusion and accessibility in children’s literature,” the spokesman added.

“The current review began in 2020, before Dahl was acquired by Netflix. It was led by Puffin and Roald Dahl Story Company together.”

The latest editions of the books include the clause: “The wonderful words of Roald Dahl can transport you to different worlds and introduce you to the most marvellous characters. This book was written many years ago, and so we regularly review the language to ensure that it can continue to be enjoyed by all today”.

Public reaction

The announcement of these latest changes to Dahl’s books met a wave of public backlash from prominent literary figures, including Salman Rushdie, who tweeted:

“Roald Dahl was no angel but this is absurd censorship. Puffin Books and the Dahl estate should be ashamed.”

Many critics are calling the changes “woke”, “pointless” and “dangerous.”

The Telegraph’s arts and entertainment editor Anita Singh said “The thing that annoys me about the Roald Dahl changes is how stupid they are.”

“A ban on the word ‘fat’ yet keeping in the rest of the description in which Augustus Gloop is clearly fat.”

Translator and writer, Anton Hur, said on Twitter: “This has less to do with censorship and more to do with an estate cynically squeezing out every last bit of money they can from the IP of a long-dead person. Not all books deserve be passed on, not every author’s work is a classic. We can let some of it go. It’s ok.”

CEO of PEN America, Suzanne Nossel, tweeted a long thread, expressing her alarm at the “hundreds of changes” to venerated works by @roald_dahl in a purported effort to scrub the books of that which might offend someone.”

“Amidst fierce battles against book bans and strictures on what can be taught and read, selective editing to make works of literature conform to particular sensibilities could represent a dangerous new weapon,” she wrote.

“Those who might cheer specific edits to Dahl’s work should consider how the power to rewrite books might be used in the hands of those who do not share their values and sensibilities. We understand the impulse to want to ensure that great works of children’s literature do not alienate kids or foster stereotypes.”

Nossel describes the “regrettable outcome” of having “beloved works” including Dr. Seuss books withdrawn entirely out of concern for causing offence.

“The problem with taking license to re-edit classic works is that there is no limiting principle,” she continues. “You start out wanting to replace a word here and a word there, and end up inserting entirely new ideas (as has been done to Dahl’s work).

“Literature is meant to be surprising and provocative. That’s part of its potency. By setting out to remove any reference that might cause offence you dilute the power of storytelling.”

Nossel believes a better solution can be made by offering introductory context that “…prepares people for what they are about to read, and helps them understand the setting in which it was written.”

“If an editor, publisher or estate believes they must go beyond that, readers should be put on notice about what changes have been made and those wishing to read the work in its original form should have that opportunity.”

“Changes should be kept as surgical as possible with expert input to uphold the integrity and authenticity of the original work. So much of literature could be construed as offensive to someone – based on race, gender, religion, age, socio-economic status or myriad other factors. Such portrayals are vital topics for discussion and debate, leading to new insights.”

Deputy literary editor of London’s Sunday Times, Laura Hackett agrees, saying the editors at Puffin “…should be ashamed of the botched surgery they’ve carried out on some of the finest children’s literature in Britain.”

“As for me, I’ll be carefully stowing away my old, original copies of Dahl’s stories, so that one day my children can enjoy them in their full, nasty, colorful glory,” she tweeted.

Dahl’s complicated legacy

Since his death in 1990, Dahl has been criticised for his history of alleged anti-Semitic remarks made during his lifetime.

In December 2020, Dahl’s family released a statement, apologising for the “hurt” his books caused.

“The Dahl family and the Roald Dahl Story Company deeply apologise for the lasting and understandable hurt caused by some of Roald Dahl’s statements,” the statement read.

“Those prejudiced remarks are incomprehensible to us and stand in marked contrast to the man we knew and to the values at the heart of Roald Dahl’s stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations. We hope that, just as he did at his best, at his absolute worst, Roald Dahl can help remind us of the lasting impact of words”.

Progressive or Futile?

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was first published in 1964 — a very different time. Back then, Dahl could describe Oompa-Loompas as African Pygmy people whom Wonka had “smuggled” out of Africa in crates to work in his factory — and for that description to not cause any offence to mainstream audiences.

We’re sympathetic to the publisher’s intentions. We understand the supposed pursuit in wanting to correct the wrongs of the past — but correcting wrongs in a few texts doesn’t systemically correct anything in the long run, does it? And if you’re going to rewrite history (there’s a supposed timelessness about Dahl’s books that can explain why he’s still being so widely read today) then what should we do about ‘offensive’ movies from fifty years ago? One hundred years ago? Why isn’t the over-famed and extremely problematic “Birth of a Nation” completely destroyed?

What about other ‘classic’ books, likeTo Kill A Mockingbird, which is problematic for a whole other host of reasons?

Correcting children’s books won’t stop children from enacting or perpetrating racist or discriminatory behaviour. If we censor words like this from old texts then we bar ourselves from having important conversations about language, and hinder our ability to explain to future generations why we wouldn’t use words like that today.

We agree with Suzanne Nossell, who concluded her tweets by saying: “If we start down the path of trying to correct for perceived slights instead of allowing readers to receive and react to books as written, we risk distorting the work of great authors and clouding the essential lens that literature offers on society.”