Feminism seeks to eradicate the inequality that underpins much of our society. Many of these inequalities are based on those of organised religion. As we become a more multi-cultural society, a more educated society, a more feminist society, these values are being questioned and eroded.

We celebrate equality and choice and constantly challenge the status quo. But how can we reconcile feminist ideology and the inherently patriarchal values of religion?

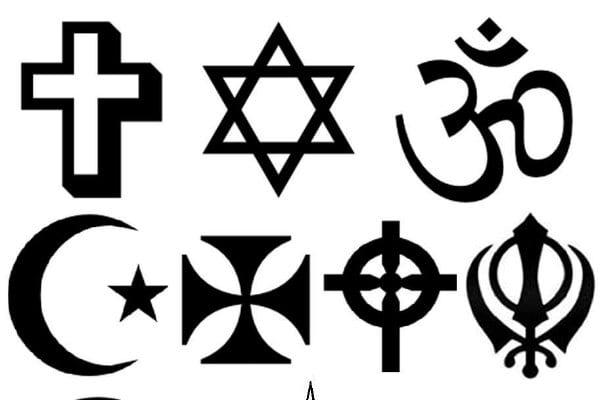

Misogynistic practice has been common place in almost all religions.

In Hinduism permission to study the Vedas comes only after the ceremony Upanayana is performed. This ceremony is exclusively for boys, thus preventing women from ever reaching the state of Moksha or Nirvana.

The Catholic Church denies women basic choice about their reproductive health. Instead the decisions are made by a system of men. A system which denies female priests and thus female voices in the hierarchy.

Islam is presently the most obvious and visible example of anti-female religious practice mainly through the wearing of the burqa. However, misogyny is pervasive and present in nearly all religion, from the very ancient Hinduism to the very modern Scientology, the role of women is consistently second to that of men.

That is not to say that feminists do not exist within these religions. There are undoubtedly intelligent, fierce, fighting women who celebrate their faith in all religious groups. However, the path to change is far more complex within the structure of religion than within an ostensibly secular society.

As a feminist and an atheist, I find it hard to merge the idea of being a feminist with being a part of an inherently patriarchal religion. The problem for me begins in childhood.

We espouse choice and equality as being the core values of the feminist movement. However, when we indoctrinate a child into a religion we deny them the freedom of choosing their own belief system.

In a world where many girls are still deprived of a basic education, the choice of religion is made for them from the moment they arrive. They are born into a structure which dictates to them their place in the world, that of being below men.

In the aftermath of the USA’s election last year one of the sorrows that was reiterated again and again was from mothers and grandmothers who had hoped that their daughters and granddaughters would be able to look up to a female president.

They wanted them to see the last great glass ceiling smashed, and for them to feel anything was possible. Yet in religion we constantly expose girls to a structure where women are excluded from the hierarchy. This contradiction of faith and feminism begs the question, is there a way to reconcile the two?

As someone standing from the outside it is hard to see an answer. Many religious feminists argue that their personal relationship with their faith and religion can sit alongside the structures that are steeped in historical patriarchy.

They argue that the religion has been perverted by human interpretation and in its purest form can be aligned comfortably with feminist ideology. As well as this, there are many women seeking to change the male-centric nature of the religion they are part of.

However, reconciling feminism and religion requires a line of questioning and challenging that the very nature of organised religion seeks to oppress. Challenging one aspect of the religion brings the fear of a collapsing house of cards.

So, in the wake of another International Women’s Day, I am seeking an answer to how feminism can become a part of religion. Can we destroy the patriarchy without destroying people’s faith?