“Please be good,” my mother would plead when I was little. I tried. I really did. But no matter how hard I worked to follow the rules, to fit in, to be the ‘good girl’ everyone wanted, something always felt off – like trying to read a book in a language I could never quite understand.

At 44, sitting in a psychologist’s office as my five-year old son received his autism diagnosis, everything suddenly clicked into place. My tears weren’t just for my beautiful boy and what this meant for his future—they were tears of recognition. Every struggle, every misunderstanding, every exhausting effort to be ‘good enough’ finally made sense. I wasn’t failing at being a ‘good girl’, I was an autistic woman trying to follow a neurotypical rulebook.

For all women, society’s ‘good girl’ expectations can be suffocating. Through my research at The Good Girl Game Changers project, we’ve discovered that by age 11, most girls learn they must earn love through perfect performance, constant people-pleasing, and protecting others at any cost. But for autistic women like me, these patterns become amplified to dangerous extremes.

My autistic brain turned perfectionism into an all-consuming mission. I could focus with an intensity that made me exceptional at structured tasks – working for days with minimal awareness of food, sleep, or my surroundings when absorbed in a project. The house could literally “burn down around me” when I was deep in analysis or writing. There was no middle gear, only full throttle or complete stop. By 34, this relentless intensity had driven me to complete exhaustion and burnout because I simply couldn’t turn it off.

While I could analyse data for days, human interactions felt like being trapped in a play where everyone else had the script but me. I’d stumble through conversations, missing jokes, misreading faces, putting my foot in my mouth, and leaving social gatherings with an aching sense of never belonging. Desperate to compensate, I turned myself into a human ATM of generosity—saying yes to everything, giving away whatever I had, taking responsibility for everyone’s feelings. Without any real sense of where I ended and others began, I became the perfect target for unhealthy relationships and exploitation.

My confusion about social rules had a dangerous dark side. Unable to trust my own perceptions, I silently suffered through abuse, apologised for others’ behavior, assumed every problem must be my fault because I’d misunderstood something again. Under extreme stress, my body would take this confusion to its ultimate extreme—I’d go completely mute, physically unable to form words, silenced by the overwhelming pressure to get it right when I had no idea what ‘right’ even meant.

My diagnosis wasn’t just an explanation. It was liberation.

Understanding my neurodivergent brain helped me recognise that these patterns weren’t personal failings but the result of trying to force my square-peg brain into society’s round holes. This realisation transformed how I navigate both my autism and those ‘good girl’ expectations.

Our research with thousands of women uncovered three game-changing capabilities:

- Self-compassion: swapping that relentless inner critic for a wise inner ally who knows every misstep is just another chance to learn.

- Secure attachment to yourself: fighting for your own wellbeing with the same fierce dedication you’ve given everyone else.

- Self-leadership: finding your voice and using it, even when that voice trembles.

These aren’t just nice theories—they’re skills I build daily through deliberate practice. I channel my intensity into focused work blocks rather than letting it run wild. I schedule recovery time between social interactions without guilt. When autism makes something challenging, I ask for help without shame or apology. My brain’s unique wiring isn’t a flaw to fix, it’s a different way of experiencing and contributing to the world.

Our research shows that more than 77 per cent of women strive for perfection to avoid criticism, while 78 per cent prioritise pleasing others to avoid rejection. For autistic women, these pressures can be overwhelming. But here’s what I’ve learned through both research and lived experience: real power isn’t in masking our differences or performing perfection—it’s in having the courage to ask that essential question: “On whose terms and for whose benefit am I living my wild and precious life?” Whether you’re neurodivergent or neurotypical, the path to freedom starts with daring to be exactly who you are.

Our research with women reveals a striking pattern: while 65 per cent feel pressured to be the ‘good girl’ others expect, those who find the courage to break free discover something remarkable – the very traits they were taught to hide become their greatest strengths. For autistic women like me, this truth is particularly powerful. The intensity that made me ‘too much,’ the directness that made me ‘difficult,’ the sensitivity that made me ‘weird’—these aren’t flaws to fix but gifts to embrace.

Whether you’re neurodivergent or neurotypical, the path to freedom isn’t about forcing yourself to fit in. It’s about daring to take up space exactly as you are, knowing that your differences aren’t just acceptable—they’re essential for creating a world where everyone can thrive.

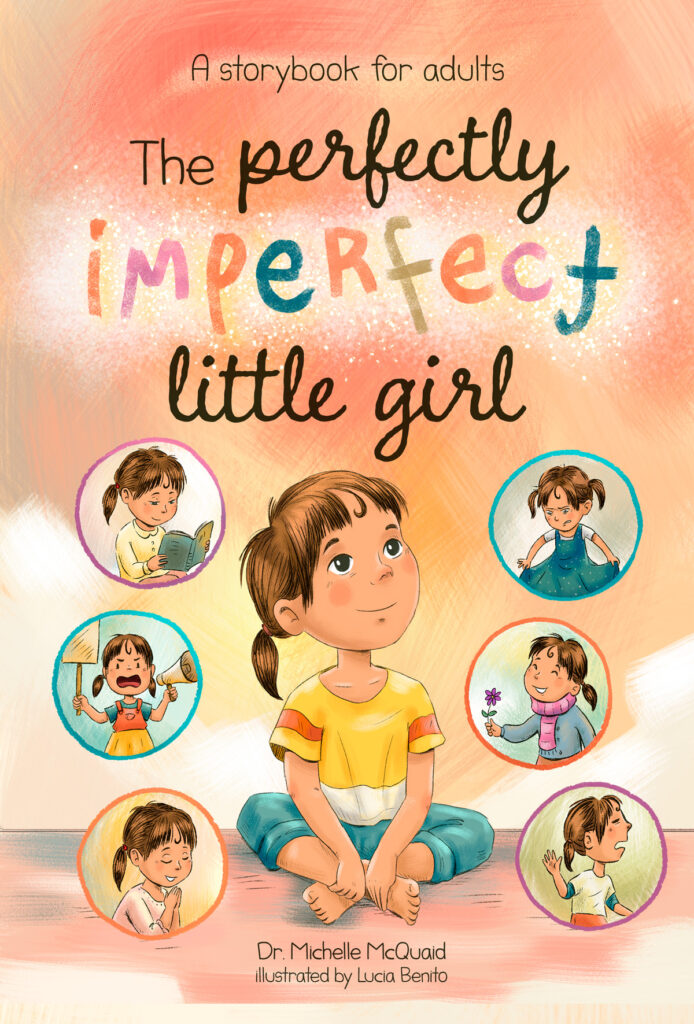

Featured image: Michelle McQuaid.