Internet trolling has changed a LOT over the past 15 years, and now there are discrepancies in the very definition of online trolling. This is a real problem, writes Evita March, from Federation University Australia, in this piece republished from The Conversation.

It seems like internet trolling happens everywhere online these days – and it’s showing no signs of slowing down.

It’s seen the British press and Kensington Palace officials call for an end to the merciless online trolling of Duchesses Kate Middleton and Meghan Markle, which reportedly includes racist and sexist content, and even threats.

But what exactly is internet trolling? How do trolls “behave”? Do they intend to harm, or amuse?

To find out how people define trolling, we conducted a survey with 379 participants. The results suggest there is a difference in the way the media, the research community and the general public understand trolling.

If we want to reduce abusive online behaviour, let’s start by getting the definition right.

Which of these cases is trolling?

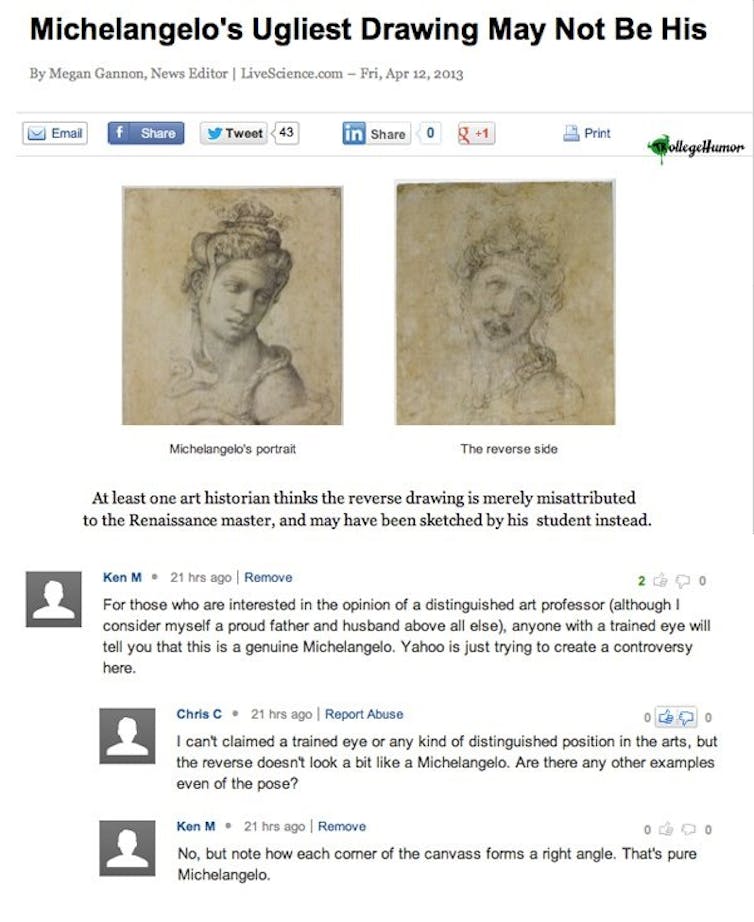

Consider the comments that appear in the image below:

Without providing any definitions, we asked if this was an example of internet trolling. Of participants, 44% said yes, 41% said no and 15% were unsure.

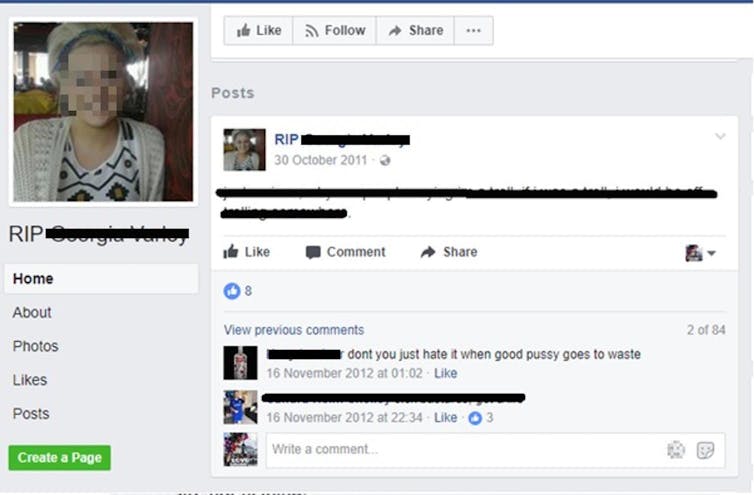

Now consider this next image:

Of participants, 69% said this was an example of internet trolling, 16% said no, and 15% were unsure).

These two images depict very different online behaviour. The first image depicts mischievous and comical behaviour, where the author perhaps intended to amuse the audience. The second image depicts malicious and antisocial behaviour, where the author may have intended to cause harm.

There was more consensus among participants that the second image depicted trolling. That aligns with a more common definition of internet trolling as destructive and disruptive online behaviour that causes harm to others.

But this definition has only really evolved in more recent years. Previously, internet trolling was defined very differently.

A shifting definition

In 2002, one of the earliest definitions of internet “trolling” described the behaviour as:

luring others online (commonly on discussion forums) into pointless and time-consuming activities.

Trolling often started with a message that was intentionally incorrect, but not overly controversial. By contrast, internet “flaming” described online behaviour with hostile intentions, characterised by profanity, obscenity, and insults that inflict harm to a person or an organisation.

So, modern day definitions of internet trolling seem more consistent with the definition of flaming, rather than the initial definition of trolling.

To highlight this intention to amuse compared to the intention to harm, communication researcher Jonathan Bishop suggested we differentiate between “kudos trolling” to describe trolling for mutual enjoyment and entertainment, and “flame trolling” to describe trolling that is abusive and not intended to be humorous.

How people in our study defined trolling

In our study, which has been accepted to be published in the journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, we recruited 379 participants (60% women) to answer an online, anonymous questionnaire where they provided short answer responses to the following questions:

- how do you define internet trolling?

- what kind of behaviours constitute internet trolling?

Here are some examples of how participants responded:

Where an individual online verbally attacks another individual with intention of offending the other (female, 27)People saying intentionally provocative things on social media with the intent of attacking / causing discomfort or offence (female, 26)Teasing, bullying, joking or making fun of something, someone or a group (male, 29)Deliberately commenting on a post to elicit a desired response, or to purely gratify oneself by emotionally manipulating another (male, 35)

Based on participant responses, we suggest that internet trolling is now more commonly seen as an intentional, malicious online behaviour, rather than a harmless activity for mutual enjoyment.

Researchers use ‘trolling’ as a catch-all

Clearly there are discrepancies in the definition of internet trolling, and this is a problem.

Research does not differentiate between kudos trolling and flame trolling. Some members of the public might still view trolling as a kudos behaviour. For example, one participant in our study said:

Depends which definition you mean. The common definition now, especially as used by the media and within academia, is essentially just a synonym to “asshole”. The better, and classic, definition is someone who speaks from outside the shared paradigm of a community in order to disrupt presuppositions and try to trigger critical thought and awareness (male, 41)

Not only does the definition of trolling differ from researcher to researcher, but there can also be discrepancy between the researcher and the public.

As a term, internet trolling has significantly deviated from its early, 2002 definition and become a catch-all for all antisocial online behaviours. The lack of a uniform definition of internet trolling leaves all research on trolling open to validity concerns, which could leave the behaviour remaining largely unchecked.

We need to agree on the terminology

We propose replacing the catch-all term of trolling with “cyberabuse”.

Cyberbullying, cyberhate and cyberaggression are all different online behaviours with different definitions, but they are often referred to uniformly as “trolling”.

It is time to move away from the term trolling to describe these serious instances of cyberabuse. While it may have been empowering for the public to picture these internet “trolls” as ugly creatures living under the bridge, this imagery may have begun to downplay the seriousness of their online behaviour.

Continuing to use the term trolling, a term that initially described a behaviour that was not intended to harm, could have serious consequences for managing and preventing the behaviour.

Evita March, is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Federation University Australia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.