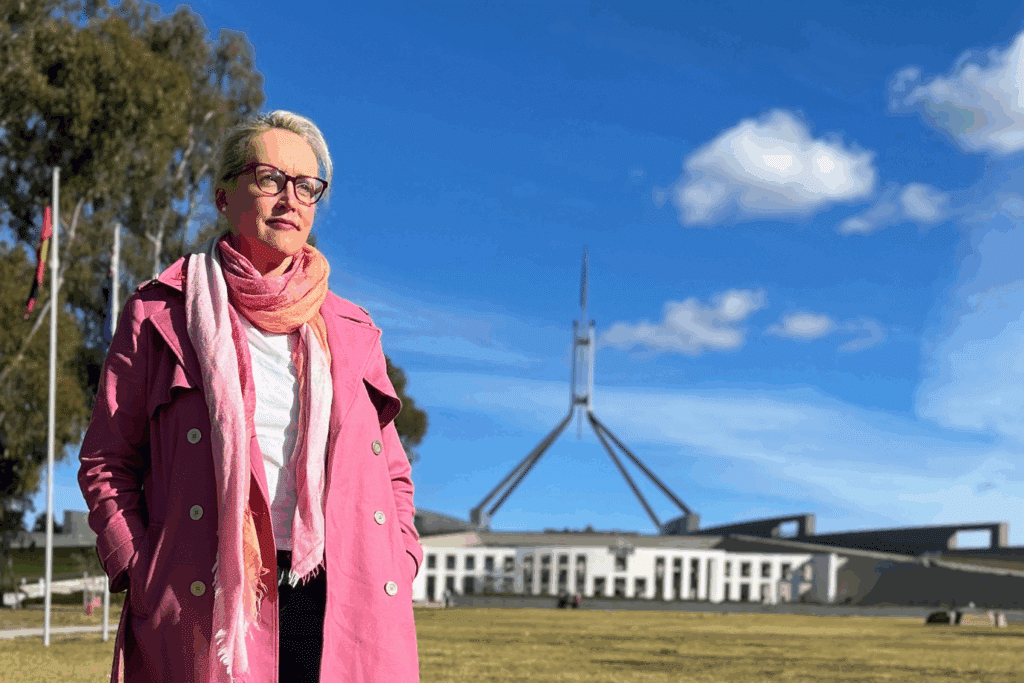

Former Chief of Staff to the Deputy Prime Minister, Jo Tarnawsky, was shocked to find herself sidelined and ostracised after raising allegations of bullying that she was experiencing from colleagues within Parliament House. She later filed legal action, and the case was settled in March 2025.

Below, Jo reflects on why complaints and allegations of workplace harm and misconduct within Parliament House continue to be dismissed, overlooked and not taken with the level of seriousness the public would expect following the Set the Standard report.

In February 2022, now-Prime Minister Anthony Albanese acknowledged the women who “bravely stood up and called out a culture of mistreatment” at Parliament House and committed the Parliament to leading by example in workplace safety and respect.

More than four years after the Set the Standard: Report on the Independent Review into Commonwealth Parliamentary Workplaces was handed down, it is fair to ask whether that promise has been kept.

On 1 October 2023, the Parliamentary Workplace Support Service (PWSS) was established as an independent statutory agency to address the recommendations in the Set the Standard Report.

Last week, the CEO of the PWSS, Leonie McGregor, laughed during Senate Estimates when she was asked whether her agency receives many complaints, and responded, “We receive many complaints.” She then told the Committee she could not provide complaint figures because the data were recorded in general categories rather than as clearly defined complaint statistics.

That moment matters.

Not only because of the misjudged tone in McGregor’s response and the outrage of survivors that followed, but because of what it reveals about how seriously harm is being treated in the very institution that promised reform. And how much progress has – or has not – been made since the Set the Standard Report.

An unkept promise

Too often, Parliament behaves as though the reckoning has passed. For the many survivors of parliamentary workplace harm, it has not.

The Set the Standard Report was not lacking in clarity. It drew on the testimony of more than 1700 people who stepped forward to tell their stories. It identified the scale of harm, named the cultural drivers that enabled it, and laid out a roadmap for reform. All 28 recommendations were accepted in full by the Parliament in 2022, alongside public commitments to implement them.

But where are we now?

Key reporting milestones linked to the Set the Standard Report are overdue. Oversight arrangements that were meant to ensure transparency and accountability have fallen away.

As one example, Recommendation 3 provided for an external, independent review to be established within 18 months of the Set the Standard Report to examine how the report’s recommendations were being implemented – not as a symbolic exercise, but as a safeguard against reform quietly drifting into complacency. Recommendation 2 provided for an annual parliamentary discussion in both Houses of Parliament.

That review – and those annual discussions – have still not occurred.

In this context, the PWSS CEO’s response during Senate Estimates regarding the “many” complaints the agency receives is a symptom of what happens when reform is treated as already ‘done’, rather than approached with the seriousness, ongoing scrutiny and humility it requires.

What these moments signal to survivors and current staffers

When complaints are treated lightly, or when systems cannot clearly explain how harm is even being categorised or tracked, that reinforces the very dynamics the Set the Standard Report sought to dismantle: minimisation, deflection and silence.

For those who have experienced harm in parliamentary workplaces, these signals are not abstract; they are read carefully. They also shape whether others will ever feel safe enough to come forward, be believed, or helped.

The PWSS was created to help restore trust and create a safer parliamentary workplace. But trust does not come from legislation or organisational charts alone. It comes from conduct, particularly when power is being exercised and when complaints of harm are raised.

Laughing in the context of complaints can compound trauma and undermine the very trust it was supposed to help build.

How leadership failures contribute to harm

Since I came forward publicly, I have been contacted by parliamentary staff from across the political spectrum whose lives and livelihoods have been harmed by their time in Parliament. Different roles. Different offices. Similar stories.

Many describe being left traumatised by their experiences at Parliament House. Many are underwhelmed – and in some cases deeply disillusioned – by the post-Set the Standard support meant to protect them.

Some of these stories are already public. For example, media reports have documented multiple allegations raised by former staff members of Senator Dorinda Cox. What was particularly instructive about that situation was the response to these allegations. When Senator Cox defected from The Greens to the Australian Labor Party in June 2025, Albanese dismissed staff allegations as having been “dealt with” — news that came as a shock to some who had made allegations. It was news also that reinforced a familiar lesson: when political advantage is at stake, concerns raised by staff remain negotiable and contingent on power, timing, and convenience.

Other stories never make headlines. Not because they are less serious, but often because the extra costs of visibility, engaging with the media, and confronting power publicly are too high in addition to their existing trauma.

I know survivors of sexual assault who have waited years for any form of resolution. One is a now-friend I check in on regularly, simply to ask how many steps she has done that day; the answer is not uncommonly around fifty. Enough to get to the bathroom, kitchen and back to bed. She will send me a photo of her bedroom window as proof of life.

Another staffer I know was subjected to unwanted advances by their employing parliamentarian. When they made it clear that those advances were not welcome, they soon found themselves pushed out of a role they had dreamed of doing their whole lives.

Another staffer quietly paid and arranged for their own psychological counselling for workplace trauma, due to a belief that it would lower the risk of consequences on their parliamentary career.

Other staffers I know have raised concerns about bullying or discrimination, only to see their perpetrators protected while they were quietly pushed out of roles they loved, leaving them unemployed and heartbroken.

The harm does not end when an incident is reported. Victims often remain isolated, traumatised and debilitated by their experience. What unites these stories is not politics, personality, or resilience. It is a system that still struggles to hold power to account and too often exacerbates the trauma on those who have already been harmed.

What happens to the “many” complaints?

If, as the CEO of the PWSS suggested, there are “many” complaints, it would be reasonable to ask what happens to those complaints next and why there has been so little visible accountability.

The Independent Parliamentary Standards Commission (IPSC) was established in October 2024 to investigate serious breaches of parliamentary standards. There is currently no public transparency about investigation findings or sanctions issued under that process.

The PWSS CEO is also the accountable authority for the IPSC, which employs 6-8 Commissioners and a support team to investigate formal complaints. No performance measures for the IPSC were published in the PWSS Annual Report 2024-2025 on the basis that it had not yet been in operation for a full year. However, it foreshadows that there will only be two reportable measures in its 2025-2026 Annual Report: the average time for an investigating Commissioner to decide how a conduct issue will be dealt with and the average duration of investigations. This seems inadequate. It appears there will be no numbers on matters investigated, no list of penalties issued, nor other useful accountability information published.

This silence raises legitimate questions. If matters are being referred, why are outcomes so opaque?

I have heard from staffers who say they referred matters to the IPSC for investigation and feel the only tangible outcome was being issued with strict confidentiality notices. According to the IPSC’s website, the penalties for breaching IPSC confidentiality obligations are imprisonment of up to six months or 30 penalty units (currently $9,390) or both.

The effect of this is chilling.

For a system established to uphold standards, the question is not merely whether complaints are being received but whether they are being resolved in a way that delivers justice, restores trust, and does not further silence those who came forward in the first place.

Processes designed to ensure accountability should not further isolate people who have already been harmed. Nor should they create a system in which complaints vanish into institutional silence, with no visible resolution and no public confidence that wrongdoing is being addressed.

Without transparency, accountability risks becoming performative. And without accountability, reform loses its meaning.

And the additional sting in the tail? The list of sanctions the IPSC can impose on a parliamentarian or employee if a matter is fully investigated and a Commissioner finds it is worthy of a sanction is not comparable in severity to the sanctions that can be imposed on a victim for breaching a confidentiality notice.

In the case of a parliamentarian, for example, IPSC sanctions are limited to a written reprimand, professional development training, a behaviour agreement, or referral of the matter to the Privileges Committee of the relevant House of Parliament. But no criminal penalties of the kind that can be imposed on victims for breaching confidentiality.

These structural imbalances sit within a broader pattern of reform mechanisms that have quietly weakened over time. The cross-party Parliamentary Leadership Taskforce has concluded its work, and there is no ongoing formal staff consultation mechanism. Architecture that was meant to sustain reform has quietly thinned, and oversight appears to have given way to inertia.

Accountability should not be optional

Reform does not sustain itself. It requires political will and continued pressure on those in power.

At a minimum, the long-promised independent external review of the implementation of the Set the Standard Report must finally occur – transparently, with wide consultation, and findings made public. Survivors deserve to know whether the reforms they were promised are working and whether their feedback is being taken seriously to inform the system’s continuous improvement.

There must also be an acknowledgement of harm.

An apology should not be so hard to find in a system that claims to value psychological safety. Silence, deflection and proceduralism only deepen mistrust. And when trust is this badly damaged, leadership consequences matter.

The role of the CEO of the PWSS is not symbolic; it carries a profound responsibility. The decisions made in this office affect human lives, livelihoods and psychological safety. The Set the Standard reforms cannot be allowed to stall or drift into complacency; they must remain active and vigilant. The PWSS plays a key role here. Public confidence requires clear evidence that complaints are being treated with the gravity they deserve and that the agency is operating independently and transparently.

Albanese said Parliament must set the standard. That promise still matters, but only if it is applied when it is uncomfortable, politically inconvenient or costly.

For the many people who have been harmed in parliamentary workplaces – and for those still working there, watching closely – the message is already clear:

This is not a system that yet knows how to take them seriously.