When the Australian Financial Review announced it was reviving the much-loved 100 Women of Influence program and rebranding it to ‘Women in Leadership’, I was genuinely excited.

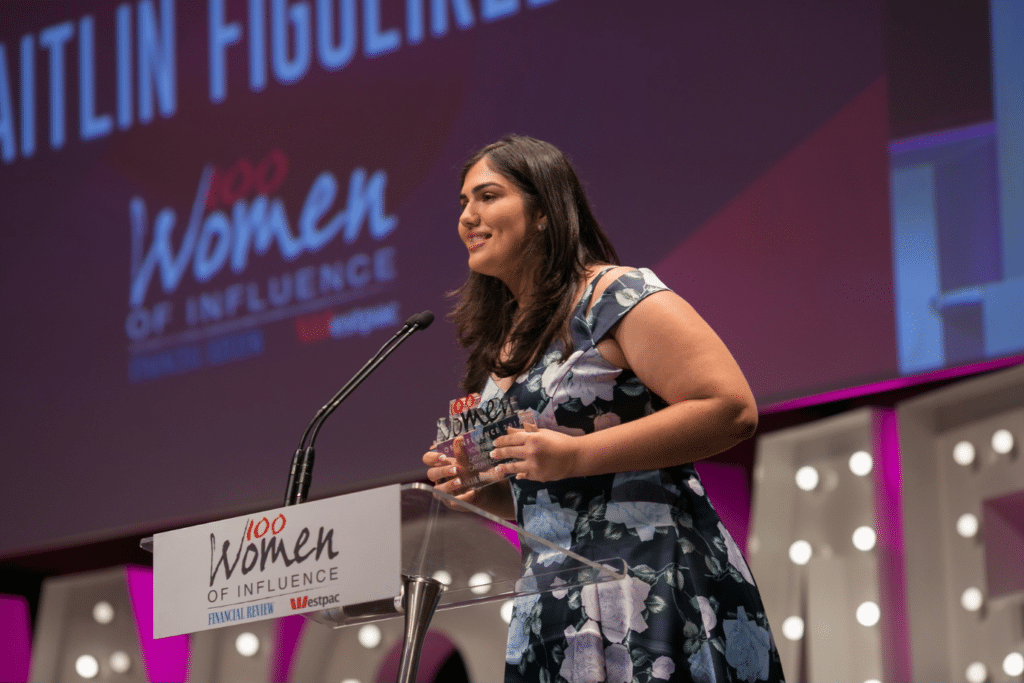

As a former 100 Women of Influence Young Leader category winner, I immediately began contacting my friends and colleagues, encouraging them to apply. Many of them are proud First Nations women and leaders from culturally and racially minority backgrounds whose presence and achievements are rarely recognised in the public domain.

From my personal experience, these women were exactly who AFR was searching for: bold and brave women from all fields and backgrounds, making a change in Australia today and inspiring the women of tomorrow.

Now, after a four-year hiatus, the AFR awards were back with a rebrand shifting focus from community impact to corporate elitism.

When the list was revealed last week, my excitement quickly turned to shock. Out of all eight categories, only one winner was not of Anglo-Saxon heritage. At least a third of the categories contained no women from diverse backgrounds, ethnicities and organisations. And of the combined ‘Government, Education and Not-For-Profit’ category, Rochelle Courtenay, founder of Share the Dignity, was the only NFP leader to be included.

I guess I was naive to believe the AFR would regroup and deliver a program “in a manner that does justice to the outstanding women it celebrates” when the program paused due to the pandemic.

Well, AFR – you shamefully missed the mark. How can your organisation legitimately say the Women in Leadership awards is a return of 100 WOI when it does not embody the spirit, integrity and inclusiveness of its predecessor?

My disappointment is not aimed at the winners or short finalists. There is no doubt that this year’s recipients are leaders in their fields and have had to overcome barriers to succeed in their traditionally male-dominated industries. Rather, I’m angry at the direction and corporatisation of the awards.

What made 100 Women of Influence unique was AFR’s active pursuit of “uncovering and promoting a diverse group of women [and young women, who] are fighting for change every day and who use their skills and ability to help change the status quo to a more equal, more diverse, and vibrant society.”

While race and cultural background were never a defining factor of 100 WOI, each of the previous year’s cohorts were substantially more diverse than these years. Take my year as an example, with category winners like Kristy Masella, CEO of Aboriginal Employment Strategy, Moya Dodd, former Vice-Captain of the Matilda’s and Partner at Gilbert + Tolbin, and myself, a 21-year-old gender equality activist of South Asian Goan descent.

The new awards purpose is also vastly different with a focus on ‘highlighting the work and achievements of those poised to enter the upper echelons of corporate decision-making’. It’s no wonder the results are the way they were.

On LinkedIn, my sentiments were shared. Frustration around the homogenous judging panel was especially notable. Nareen Young, Associate Dean (Indigenous Leadership and Engagement) and the inaugural 100 WOI Diversity Category Leader called “the composition of the judging panel utterly shameful.” Another pointed out the hypocrisy that “men [had] a seat before blak women or multicultural women.” Did any of the judges ask the necessary question: who’s not at this table?

In my opinion, there are four main reasons why 100 Women Of Influence worked:

- Each year, the awards recognise 100 women from all kinds of fields and stages of their careers.

- There were ten expansive categories to attract diverse talent.

- Recipients were selected based on having an impact-driven purpose rather than corporate potential.

- A diverse and inclusive judging panel.

Categories such as Social Enterprise and NFP, Diversity and Inclusion, Innovation, Public Sector and Business and Entrepreneurship were cut and replaced with Retail, hospitality and property, Resources, industries and utilities, and two categories for financial services.

Losing these categories was the wrong decision. How can the judges fairly compare small organisations or NFPs against applicants from multimillion dollar companies like KPMG, Westpac or Telstra? Or feature green energy start-ups in a category stacked with mining companies such as Rio Tinto, BHP and Perenti?

It’s not like this year’s applicant pool was so shallow. I personally know two examples of women, one who is an incredible First Nations leader and another multicultural leader who applied and were not selected or shortlisted by AFR. Both women have faced barriers at the intersection of ethnicity, gender, and race, and yet through their resilience have led an exceptional leadership journey and in my opinion are among the nation’s most influential female leaders. Their innovation, tenacity and forward-thinking businesses are exactly who the AFR should highlight in their awards. After all, they are the ones quietly changing the future of Australia from pushing back against a broken system.

Under 100WOI I have no doubt these women would have made the list. However, it’s apparent under the new model neither of these women ever stood a chance with a judging panel that clearly selected winners who fit their vision and corporate status of Australian leadership.

It’s apparent neither of these women ever stood a chance with a judging panel that clearly selected winners who fit their vision of Australian leadership.

Whether you are pro-awards or not, recognition by companies like the AFR has the potential to change lives and open new doors and opportunities. It did for me.

There is a tried-and-true saying, ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’, and for the next generation of leaders, Women in Leadership has turned off the lights.

AFR, do better.