The manosphere appeals to its audience because it speaks to the very real lives of young men under the above factors – romantic rejection, alienation, economic failure, loneliness, and a dim vision of the future, writes Ben Rich, Curtin University and Eva Bujalka, Curtin University in this article republished from The Conversation.

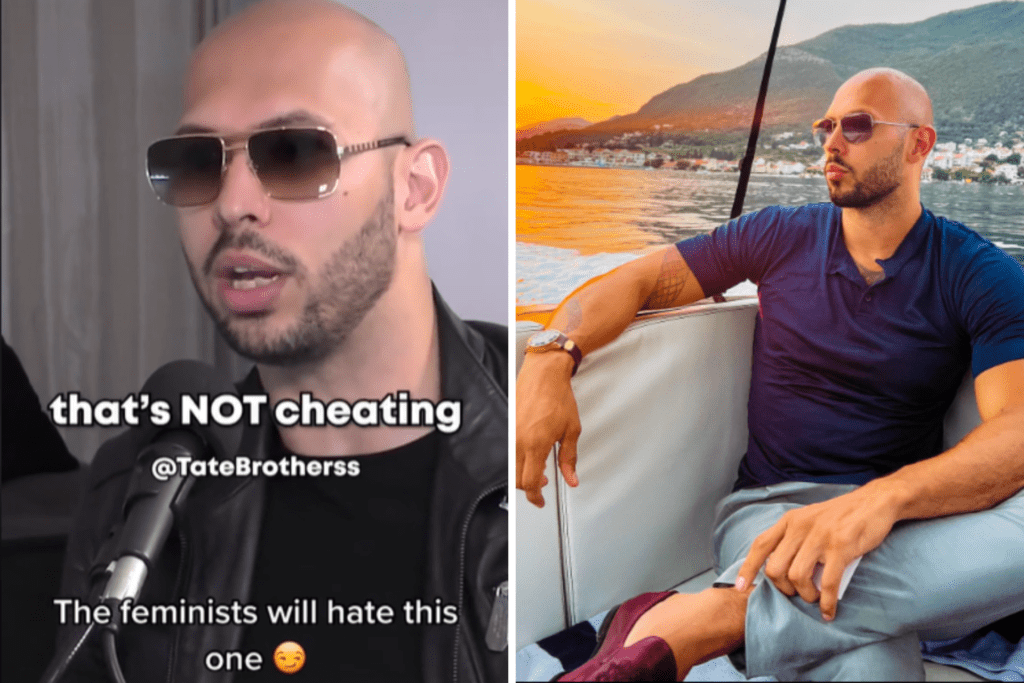

Mega-influencer Andrew Tate is once again back in the news as he battles charges of organised crime and human trafficking in Romania.

Tate gained infamy last year after being banned on most major social media platforms for promoting a variety of aggressively misogynistic positions designed to stir controversy and draw attention to his brand.

But while widespread public attention was drawn to Tate only recently, his reputation as a thought leader and “top g” in the online “manosphere” community has been longstanding.

Indeed, Tate’s ability to stoke and exploit the anxieties and grievances driving the manosphere are unprecedented, and have played a key role in him amassing millions of fans and hundreds of millions of dollars.

The lure of the ‘manosphere’

The manosphere is an overlapping collection of online men’s support communities that have emerged as a response to feminism, female empowerment, and the alienating forces of neoliberalism.

While this is widely understood, a lot less energy has been directed to understanding why and how men are attracted to these extreme communities in the first place.

The manosphere’s appeal can be perplexing, particularly for parents, teachers or friends trying to make sense of how the men in their lives suddenly adopt aggressively misogynistic views.

But while the community’s content presents deeply concerning perspectives on women, it also offers explanations for, and solutions to, a very real set of issues facing young men.

A tranche of data illustrates these growing challenges. Men are rapidly falling behind in education engagement and outcomes. Rates of young male economic inactivity have risen considerably over the past two decades.

The intimate relations of young men also appear to be in decline. One report suggests rates of sexual activity have dropped by nearly 10% since 2002.

Suicide rates have risen significantly in men in particular over the past decade.

We’re also facing a loneliness crisis, which is particularly concentrated in young people and men.

The manosphere appeals to its audience because it speaks to the very real lives of young men under the above factors – romantic rejection, alienation, economic failure, loneliness, and a dim vision of the future.

The major problem lies in its diagnosis of the cause of male disenfranchisement, which fixates on the impacts of feminism. Here it contrasts the growing challenges faced by men with the increasing social, economic and political success experienced by women. This zero-sum claim posits that female empowerment must necessarily equate to male disempowerment, and is evidenced through simplified and pseudoscientific theories of biology and socioeconomics.

For many young men, their introduction to the manosphere begins not with hatred of women, but with a desire to dispel uncertainty about how the world around them works (and crucially, how relationships work).

The foundations of the manosphere may not strictly centre on misogyny, as is popularly imagined, but in young men’s search for connection, truth, control and community at a time when all are increasingly ill-defined.

Profiteering off anxiety

Since its inception, the manosphere has been rife with predatory influencers seeking to profit off the anxieties unleashed by this ambiguity.

Driven by a desire to reassert a romantic masculine aesthetic ideal in a world of social media unrealities, members of the manosphere often become willing consumers of a wide variety of products and services to “solve” their problems. These range from vitamin and gym supplements, personal coaching, self-help courses, and other subscription-based services.

But the influencers aren’t just capitalising on a sense of crisis passively – they actively cultivate it, as our research shows.

Figures like Tate, Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson and “alpha” strongman Elliott Hulse expend huge amounts of energy and capital fomenting a sense of crisis around these issues, and positioning themselves at the centre. No more clearly was this illustrated than in Tate’s “Hustler’s University”, which created a series of exclusive chat rooms promising men a solution to their fears and centred on Tate’s personage and teachings.

Such communities solidify the claims made by their leaders, creating feedback loops that contribute to a climate of tension and hysteria. Members are actively encouraged to ridicule those who aren’t willing to acknowledge the “feminist conspiracies” that supposedly underpin the social and political world. Non-believers are seen as contemptible, weak and ignorant, dismissed through an ever-growing newspeak lexicon as “simps”, “cucks” and “betas”.

The community can also be mobilised to spread the message and brand of the influencer to the wider public, as demonstrated by Tate.

Having successfully isolated and indoctrinated community members, influencers can then rely on them as a persistent source of support and revenue, allowing them to further reinvest and continue this cycle of growth. This suggests a key way to push back on the wider effects of the manosphere is the targeted disruption of such feedback loops and the prevention of future ones emerging.

Empathy, patience and support

Tate and the manosphere didn’t manifest spontaneously. They’re symptoms of a deeper set of challenges young men are facing.

These problems won’t be addressed by simply deplatforming people like Tate. While this may often be necessary in the short term, savvier influencers will inevitably emerge, responding to the same entrenched issues and employing the tactics to greater effect, while avoiding the mistakes of their predecessors.

In confronting the manosphere we need to understand and take seriously its appeal to lost men and the centrality of influencers in this process. We can be as critical of it as we want to be. But we also need to understand what it provides for many: a community and place of belonging, a defined enemy, direction, certainty, solutions to deep and systemic issues and, perhaps most importantly, hope.

We also need to avoid the kneejerk stigmatising and dismissal of people who fall into the manosphere. Simple ostracism tends only to entrench attitudes and reinforce the narratives of persecution spun by Tate and his ilk.

Instead, we need to use empathy, tolerance and patience to support men in ways that lead them away from these unpleasant boroughs of the internet and make them feel connected with wider society.

Ben Rich, Senior lecturer in History and International Relations, Curtin University and Eva Bujalka, Co-director, Curtin Extremism Research Network (CERN)., Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.