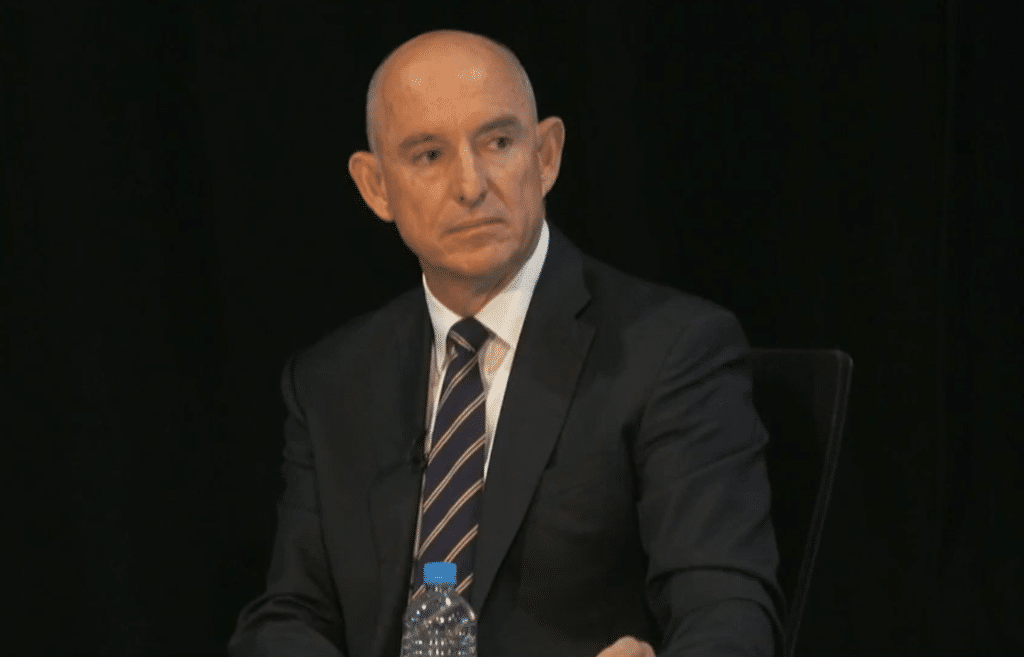

Stuart Robert could personally see “massive” issues with the Robodebt program back in July 2019. Yet at that time, he went on national TV regardless to emphatically defend the scheme.

Why? Because, as the Liberal MP said giving evidence at the Royal Commission during its nine weeks of evidence, “as a dutiful cabinet minister, ma’am, that’s what we do.”

The Ma’am he was referring to was commissioner Catherine Holmes, who quickly shot back: “misrepresent things to the Australian public?”

Commissioner Holmes has been leading the royal commission into the disastrous program that not only resulted in a $1.8 billion government settlement to hundreds of thousands of victims, but also an ongoing cost to the Australian public that goes well beyond mere financial figures alone. Commissioner Holmes is due to report back on the findings and recommendations by June 30.

Robert, the Liberal MP and now former minister claimed it was an act of “cabinet solidarity” to defend government programs even when you don’t agree with them. He said that he’s actually implemented “many things” that he “passionately disagrees with” but that he’s still required as a minister to represent such programs and defend them, and that’s what he did with robodebt.

During the public hearings, we’ve heard from more than 100 witnesses on the scheme that chased money from welfare recipients from 2015 to 2019, despite plenty of concerns about its legality along the way.

We’ve heard how some of Robodebt’s victims — the Commonwealth was later found to have acted unlawfully in chasing this money — were impacted, sometimes with family members having to step in to give evidence due to the victim no longer being alive. Such witnesses included Kathleen Madgwick, speaking on the experience of her only child, Jarrad, who took his own life at the age of just 22 — within hours of learning about a $2,000 Centrelink Robodebt. Madgwick told the Commission that her son was distressed on learning about the debt, but it’s only during these public hearings that she’s learned he never spoke to a real person. She also shared how she had written to the then prime minister Scott Morrison to get more answers following Jarryd’s death, but received no response, “not even a sorry for your loss,” she told the commission.

The evidence shared over these past few weeks has been gutwrenching and horrific, but more so it’s been overwhelmingly frustrating as we learned more about who knew what and when — as well as what, if anything, they did to speak up about the failed system and its consequences.

We especially learned about the consequences of “dutiful cabinet men”.

While Stuart Robert had “massive personal misgivings” about the scheme, he said he was waiting on the solicitor general’s advice before doing anything more or even raising such concerns publicly. He didn’t announce a “refinement” of the program until November 2019. Sadly, as the commission heard, the second half of 2019 saw another 50,000 unlawful debts raised.

The “cabinet duty” Robert was referring to in justifying his non-action, is not entirely clear.

Robert had supported former Prime Minister Scott Morrison in securing the numbers he needed to win a leadership spill against former PM Malcolm Turnbull – and Robert was quickly brought back into the cabinet as Minister for Government Services during Morrison’s first ministry, which saw him taking on responsibility for robodebt.

He didn’t invent the scheme, and he wasn’t the first to miss seeing the urgent necessity to dump it – other dutiful ministers may take some blame for that. The missed opportunities started early, as far back as 2014 with legal advice from the Department of Social Services that raised concerns. Then later the Commonwealth Ombudsman launched its own investigation, and later again a shelved PricewaterhouseCoopers report declared Robodebt needed to be remodeled. And later still, external legal advice from Clayton Utz that found Robodebt was illegal.

But by 2019, Robert was responsible for a program that he now says he had “personal misgivings” on well before he ever announced any refinements. Another witness at the royal commission, Renee Leon, gave evidence saying that Robert has been provided with the legal advice suggesting the scheme was unlawful, but he’d chosen to ignore it.

So what was Robert’s cabinet duty, and does it or should it stand in the way of a separate duty to hundreds of thousands of Australians?

Robert’s been a member of parliament since 2007, having served across a wide range of portfolios including as the Minister for the NDIS, the Minister for Human Services, the Minister for Government Services, the Minister for Employment, and the Assistant Minister for Defence.

He has multiple degrees. He attended the Royal Military College Duntroon, completed a Masters in Business Administration and a Masters in Information Technology at the Queensland University of Technology and even more qualifications that could arguably make him one of the most educated people in Parliament.

And yet? At a time when it mattered most, he referred to a sense of duty, to his own sense of “solidarity”.

That solidarity was to the Morrison Government — at the time. He was, after all, close to former prime minister Scott Morrison, and from the center-right of the Liberal Party.

And his ministerial career had been brought into question a number of times prior to Morrison becoming PM. He had been dropped from Turnbull’s ministry after controversially attending a Beijing event back in 2014, where a China state-controlled mining company signed a deal with an Australian resources company, with a chairman who was a close friend of Robert. Robert denied it was an official government visit, saying it was in a “private capacity”.

Later in 2017, news emerged that Robert had founded a company that has been awarded millions of dollars in government contracts, and may therefore have made him constitutionally ineligible for parliament — he was able to avoid being swept into the eligibility crisis that brought down other MPs at that time, on a technicality.

On Christmas Eve of 2021, he controversially vetoed a number of research grants that all happened to be in the humanities space and, according to Robert, were not within the “national interest”.

Clearly, Stuart Robert has had plenty of education and years of experience as an MP. Perhaps he could have benefitted from more studies in the humanities space after all.

Robert’s sense of misplaced solidarity and cabinet duty raises the question, why is he in parliament at all? What is the point of a political career if not to call out terrible policy and programs, especially when know and directly see how bad they are?

Robodebt is an example of extreme policy failure involving multiple hands over many years, a program that was unlawful from the outset, not because of a legal technicality or initial mistake made when putting it into action. Rather, as Professor Peter Whiteford previously explained, any reasonable person with some understanding of the social security system could have seen that attempts to recover “overpayments” by using income averaging would be wrong.

Any reasonable person should have been able to foresee what such letters could do to already vulnerable people. This kind of policy failure explains why we have a parliament over a dictator, a cabinet instead of a despot.

And yet, as so often is the case with so many of these dutiful cabinet ministers, there is a sense of solidarity that occurs regardless of whether it serves the country or not.