I am now convinced of the deep contempt that Prime Minister Scott Morrison has for women.

In April, I was briefly hopeful. While the world reeled from an unexpected pandemic, childcare became free and small business support meant that a number of women in my personal sphere did not lose their jobs. I thought I had underestimated the Prime Minister and his government.

In the last few weeks, that hope has turned to frustration, and finally fury at what must be one of the more egregiously contemptuous responses ever to be spoken on the floor of our Parliament, a place not known for kindness, fairness or honesty, from any side of politics.

On Wednesday, Alicia Payne, member for Canberra, addressed a question to the Prime Minister.

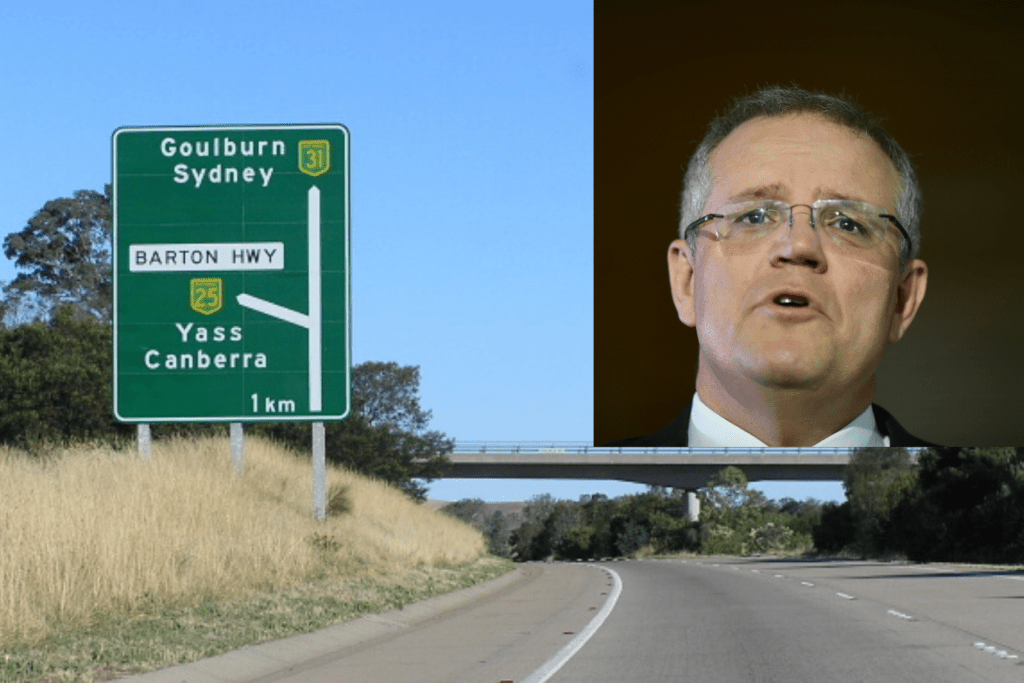

“Women from the Yass Valley are currently forced to travel an hour to Canberra or Goulbourn to give birth. As a result, a number of women have been forced to give birth on the side of the Barton Highway. Does the Prime Minister agree that this is unacceptable?” she asked.

The Prime Minister shuffled his notes, and rose in reply, a satisfied smile on his face. Was he going to announce a new maternity service? A plan?

“Well, I’m pleased to let the member know that that’s why we’ve committed $150 million to upgrade the Barton Highway…” he started with a sly smile, to chortles from the right.

Yes. That’s correct. Apparently, giving birth by the side of a highway is a joke to our Prime Minister and his buddies.

Someone who doesn’t think it’s a joke is Dr Kirsten Connan, an obstetrician and gynaecologist who has worked in Victoria, the Northern Territory and now Hobart.

Her day to day role is taking care of high-risk pregnancy in a state with a reducing number of maternity services. Like all obstetricians, she has treated plenty of women who have birthed soon after arriving in hospital, and whose babies have required resuscitation. The outcomes for those infants would be very different had their mothers birthed by the side of the road.

This opinion is borne out as fact in various neonatal mortality statistics. In 2018, the Sunday Mail reported that 23.3 babies per 1000 were dying in Queensland towns without maternity services.

This compares to a national average of 9.7 per 1000 births in 2013-2014, as reported by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Rural Maternity Taskforce, convened in August 2018, found that in Queensland, between 1996 and 2005, there was a significant decrease in the number and capacity of birthing services, with the greatest loss in rural and remote areas.

As a consequence, the average rate of perinatal death was 1.6-1.7 times the rate in inner and outer regional areas, and the rates of babies born before arrival to hospital were increasing. Even antenatal care suffered, with 22 per cent of all women and 34 percent of Indigenous women not able to attend the minimum recommended number of antenatal visits.

These appalling statistics exist even before we disaggregate them into Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. Nationally, Indigenous women face rates of stillbirth up to 60% higher than non-Indigenous women, and neonatal mortality rates up to three times higher than non-Indigenous women.

In Victoria, my own home state, an increasing number of rural maternity services are closing. In Maryborough, Castlemaine, and Traralgon, maternity services are under review. In Cohuna, forty-five minutes from Echuca, there is only one practitioner. The maternity unit in Kyneton closed last year. In the federal Health Minister’s own electorate of Flinders, some women have had to drive almost an hour to give birth since 2007.

Despite the fact that Victoria is densely populated and driving times are lower than in most other states, women and babies still face life-threatening challenges.

Dr Nisha Khot is an obstetrician and gynaecologist working at both The Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne, and at Djerriwarrh Health Services in Bacchus Marsh, a smaller hospital on the outer fringe of Melbourne, at least half an hour from the closest metropolitan maternity service. She gave me examples of some of the unexpected deliveries that she has performed at Bacchus Marsh.

Labouring mothers with high risk pregnancies, living more than forty-five minutes away from the metropolitan hospital they have been told to deliver at, have simply not been able to keep going; their babies, requiring resuscitation at birth, would have died if they had tried.

Equally, Dr Sarah Van der Wal, an obstetrician and gynaecologist in Bendigo shares similar stories of being in the right place at the right time. They also work two days a week at Echuca Base Hospital, where they and the dedicated GP obstetricians often deliver babies who may not have survived if their mothers could not present there, and had been forced to keep driving or had delivered on the road. They consider Echuca a great success story in support of reviving rural maternity services.

These burdens on women living in rural and regional Australia are well known, and are growing. They are known to the medical community and to women themselves, with a survey of 210 Tasmanian women in 2014 showing that the predominant challenges faced by pregnant rural women were cost, and the risk of labouring en route to maternity services. This study concluded that the situation rural women find themselves in may well be as a result of a strategy of transferring costs and risks of managing pregnancy and childbirth in rural areas from health care systems onto rural women themselves.

As a woman who has been pregnant and who has laboured, who has been terrified and overwhelmed by my labour, I cannot imagine doing it in a car, on the open road – but Australian women do this every single day. Sometimes they and their babies are ok. Sometimes they are not.

But I don’t think you need to be a woman who has laboured, or even a woman, or even a parent at all, to have sympathy for those in that position. Caring about the safety of a labouring mother, and the well-being of a newborn child must be one of the most fundamental instincts of humanity. An instinct the Prime Minister appears to lack.

Recently, @ranzcog was awarded a government grant to map the maternity & gynaecological services across rural, regional and remote Australia, & to document the barriers to effective service delivery @ScottMorrisonMP @GregHuntMP @MarkCoultonMP #auspol @leighsales @coopesdetat 2/2

— RANZCOG President (@RANZCOG_Pres) June 17, 2020

The Prime Minister did go on and talk about health care funding, after his glib remarks about improving the road that women were forced to birth on instead of the broken systems that have caused this to happen. And I acknowledge that the issues of workforce capacity and health care resourcing in rural areas are complex, and have suffered from bipartisan neglect.

In part, no amount of resourcing will solve the service delivery conundrum if the medical profession and training Colleges cannot find creative ways to support students and trainees in medicine and midwifery to study, live and lay roots in rural communities.

But it should be noted that the Member for Canberra was not asking the Prime Minister for an immediate solution. She was simply asking for acknowledgement that the situation of women living a mere hour outside the capital of an economically developed nation being forced to give birth by the side of the road, at grave danger to themselves and their babies, was unacceptable.

And the Prime Minister of Australia, who could have agreed that it was unacceptable, before talking about health care funding and whatever party achievement he wanted to point at, did not manage a single moment of grace and humility in recognising the literal labour performed by millions of women around the country, and the risks and challenges faced by a significant proportion in undertaking that task.

Frankly he, and everyone who chortled along with him, or were complicit in their silence, should be ashamed. The women of Australia deserve better.