“The first point is that none of this would be possible without the kids having an amazing mum. That’s true for me and for Josh. But it’s about priorities. Little rituals are important. You’ve got to talk every day and we try to do it twice a day. We do FaceTime when we can. Little things, like: ‘Where are you today?’ You hold the camera phone up and you show them where you are. My kids have grown up while I was in politics and I think that’s a good thing, on balance, because life is more normal to them. Jen and the girls almost never come to Canberra. We have our friends and our family that we socialise with and they’re very disconnected from the world of politics. It means our kids are growing up in a normal environment and that’s very important to us.”

These were the initial responses journalist Annabel Crabb elicited from the Treasurer and the Prime Minister when she enquired as to how they manage their work and family responsibilities. She reframed and rephrased in an attempt to obtain more practical responses to ‘how they make it all work’.

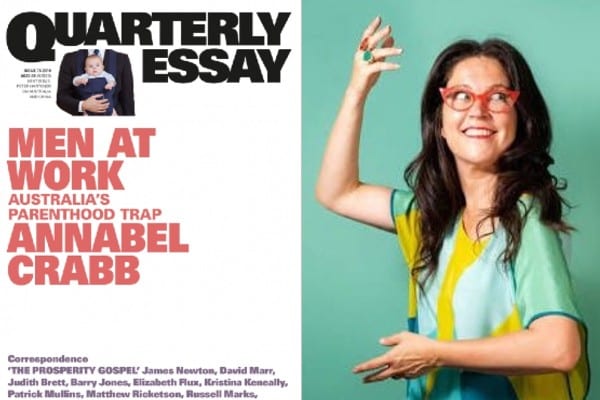

What she was actually seeking, she explains in a newly published Quarterly Essay: Men at Work, was their version of the spiel that ‘working mothers [answer] with such lavish regularity that their answer is like a little psalm they know by heart.’

Her own is this:

“Well. Mondays Jeremy works half a day from home, so that’s my day of working like a normal person. Thursday and Friday the kids are at after-school care, Tuesday and Wednesday are a crapshoot; sometimes I’ll come home from work for school pick-up and go back to work after they’re in bed, or hit up the favour bank, which – in my neighbourhood of school parents – is a busy institution of daily withdrawals and deposits. (I’ll pick your kid up from piano on Tuesday if you’ll take mine to gymnastics Wednesday. I’ve got a vat of bolognese sauce to feed ten kids if you’ll look after mine for a few hours from three.) I do most of the cooking; Jem does grocery shopping, laundry and school forms. Some days it all works smoothly. Some days it’s a debacle.”

Two things were immediately apparent to Annabel Crabb from her interviews with the first PM and Treasurer in Australian history to both have school-aged children and below while in office.

First, neither Frydenberg nor Morrison were accustomed to being asked these questions. Second, notwithstanding their evident love and devotion towards their wives and their children, neither contributes “much practical horsepower to the engine that keeps a family running”. Their spouses do that.

Crabb presents these observations, kindly, to display the still-wild deviation between the lives of the average working father, compared to the average working mother.

Having Crabb’s mind and pen poised on the subject of ‘Australia’s Parenthood Trap’ is a gift. As in her 2014 book The Wife Drought, she is able to elucidate the enduringly stubborn gap that remains entrenched between mothers and fathers in Australia with insight, acumen, humour and generosity.

It’s hard to find a more compelling visual depiction of this chasm than the one below. It’s the work of Jenny Baxter, a researcher at the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and shows how men and women’s working patterns change upon the arrival of a baby. For men, it barely changes. For women, it never recovers.

This graph just blew me away. It describes what happens to men and women when they have a family. And this does not even begin to be captured in 'relative to opportunity' assessments in grant funding #WomenInSTEM @annabelcrabb pic.twitter.com/y3CRhRU0ko

— Prof Felice Jacka OAM (@FeliceJacka) September 8, 2019

The purpose, nor spirit, of Men at Work is not to denigrate or castigate men for not doing more: it explores and examines the many barriers that prevent them from doing more.

“What I want to know is: why do we expect so little of fathers? Why do we fret so extensively about the impact on children of not seeing their mothers enough, but care so little about what happens when it’s Dad who’s always away? Do we think dads are just for weekends? Or are we simply so roundly prepared – based on what we see – for their absence that we neither mourn it nor remark on it?”

Crabb forensically unpicks the various policies and structures that help keep Australian fathers in the same narrow strait jacket their own fathers wore.

In 1991 about 4 per cent of Australian families with kids under eighteen had stay-at-home fathers. These days, according to the latest census, it’s 5 per cent. That’s a single percentage point different in twenty-five years.

According to the Australian Institute of Family Studies, using census data on families with at least one child aged under 12, more than 40% of these mothers work part-time. Only 4 per cent of the fathers work part-time.

Crabb also highlights some of policies and techniques that companies, countries and individuals are employing to help dads do things differently. From intentionally inclusive and generous parental leave schemes for dads, to progressive and unashamedly feminist policies around childcare and paid parental leave in the Nordic countries, to men like Clarke Gayford and Tim Hammond who are publicly declaring their decisions to work and parent differently.

Ultimately Men at Work confirms that the true force to be reckoned with, should we have any hope of shifting the dial more than a single percentage point in a quarter of a century is “the extraordinary, almost tectonic power of human assumptions.”

The assumptions embedded in so many of our workplaces, our families, our governments, our communities – about men as fathers and women as mothers – are what continue to inform and influence, directly and indirectly, how men and women work and live.

As the graph above shows: in the main, women work and parent, and men work.

Despite the PM and Treasurer both having peculiarly demanding and unusual hours, they are unlikely alone in not having a spiel down-pat to explain how they juggle their family responsibilities with their job because they don’t have to.

For a working mother, even the idea of not needing to know the spiel, the intricate logistical details about how each member of the household will be dressed, fed, equipped, delivered, collected, loved, cared for, entertained, as required, on any given day, and how the paid work commitments will be satisfactorily fulfilled, even for a few days, is a luxury they are unlikely to enjoy often.

How much of this is learned and perpetuated simply because ‘it’s the way it’s always been’ needs to be interrogated.

In this essay Annabel Crabb admits that there was a time she was routinely incensed that any woman with any degree of seniority or accomplishment was, inevitably, asked in interviews how they manage the multitude of their responsibilities.

Reading a heartfelt post by a Silicon Valley executive, Max Schireson, announcing his decision to step down from the company he founded changed her mind. He wrote honestly about how consuming the stress of managing his role as CEO with the ‘constant separation’ from his family was. He said the one thing no one ever asked him about was how he managed being a CEO and a dad.

“It’s a bloody sensible question,” Annabel Crabb writes. “Now I just get mad when male leaders aren’t asked it. Not asking is actually, in itself, quite a powerful message. It says, “No one expects you to care about this.” It says, “It’s not your job to worry about that stuff.” It says, “Whatever efforts you do make, or whatever private griefs your big job cloaks, are not of interest to anyone.” And for an increasing number of young fathers who do want to live their lives differently from the way their own fathers did, that’s an insult.”