The Stella Prize is one of Australia’s major literary awards, celebrating Australian women’s writing. The shortlist for this year’s $60,000 prize has been announced, with works of fiction taking four out of the six coveted spots on the list.

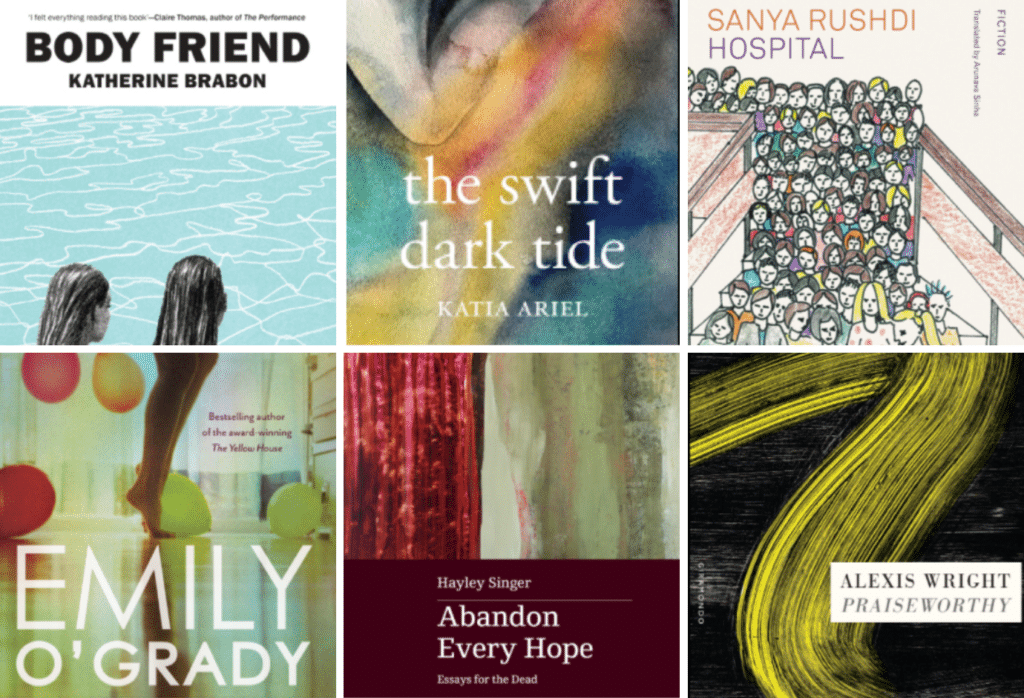

In alphabetical order, the shortlisted titles are:

The Swift Dark Tide (Nonfiction) by Katia Ariel, published by Gazebo Books

Body Friend (Fiction) by Katherine Brabon, published by Ultimo Press

Feast (Fiction) by Emily O’Grady, published by Allen & Unwin

Hospital (Fiction) by Sanya Rushdi, published by Giramondo Publishing

Abandon Every Hope: Essays for the Dead (Nonfiction) by Hayley Singer – Upswell Publishing

Praiseworthy (Fiction) by Alexis Wright, published by Giramondo Publishing

Stella’s Executive Director & CEO, Fiona Sweet, said the judges were unanimous about the titles on the shortlist.

“It was really evident to the judges, exactly who would be on the shortlist,” she told the ABC. “And they were really excited. Actually, they said [they were] joyful. They felt that these books earned their place [on the shortlist].”

The shortlisted authors will each receive $4000. Each year, new judges are selected to read hundreds of books submitted to the prestigious prize — worth $60,000. This year’s judges are poet Cheryl Leavy, poet Eleanor Jackson, writer Bram Presser, historian Dr Yves Rees and Chair, Beejay Silcox.

“All of life and death is here in these pages: illness, madness, love, sex, slaughter, parenthood, sovereignty, climate, Country,” Silcox said in a statement. “But none of the books on this shortlist tell readers what to think. They do not hector, lecture or preach. Rather, they open spaces for doubt and self-examination; for disagreement and camaraderie; for rage, absurdity and exultation; for the grotesque and the gorgeous.”

“They invite us in. And they trust us to make up our own minds. This is the quality that distinguished them in the judging room: their mighty generosity.”

The judges read 224 entries this year, and will announce the winner on May 2 at the State Library Victoria.

What the judges said

The Swift Dark Tide by Katia Ariel

“In delicate and delicious strokes, Katia Ariel’s The Swift Dark Tide renders the discovery and release of the “hidden self” in middle age. It is no mid-life crisis. Rather, it is a mid-life realising of desire and possibility; of queer becoming.”

“Ariel’s memoir reads as an unabashed re-telling of meticulous diary entries, kept to provide a constant during her love affair with a woman, a period of welcome change.”

“There are other constants: a husband who has carefully soldered their love at its many seams; and their children. It would have been easy to square both life and the memoir on that obvious binary –family or the love of “another woman”. Ariel instead follows the scent of her unquiet body, and what she herself describes as its “animal” intent on triumph.”

Body Friend by Katherine Brabon

“In her 1930 essay “On Being Ill”, Virginia Woolf lamented the deep inexpressibility of pain. “English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear,” she wrote, “has no words for the shiver and the headache.” Katherine Brabon’s Body Friend is an assured rejoinder. A gentle novel of ungentle things.”

“The narrator of Body Friend lives with/in/through chronic pain. She exists in that hushed and lonely realm that so many of us know – alienated and erased by a culture that treats bodies (and brains) as machinery to be “fixed”. Two new friendships offer her comfort: the first is with Frida, who swims laps alongside her at the pool; the second is with Sylvia, who offers tea and placid conversation. Frida pushes the narrator to her limits. Sylvia honours those limits. The narrator is torn between these women and their duelling philosophies of care. Can the two friendships co-exist? Is it possible to feel whole in a world that is determined to see you as broken?”

“There’s no grand crisis in Body Friend, no red urgency – it is serene and meditative, rich and honeyed. This is a novel of experiential heft and eloquence, which gives shape to the complexities of chronic pain by giving it human form. It is also a tale of friendship – the deep solace of mutual recognition.”

Feast by Emily O’Grady

“In Feast, O’Grady deploys a tight quorum of characters to the Scottish Highlands for the novel’s titular meal, bringing together the quintessential “mixed blessing” family. While events take place over a few brief days, the story unearths complexities, secrets, derelictions and joys that span decades and occupy the seamy continuum between good and evil, dignity and contempt, life and death.”

“Told from the perspectives of three connected women, Feast reminds us not so much to be wary of unreliable narrators, but of the deep subjectivity of moral value, the unsettling implication that we are – each of us – capable of committing and condoning so much, without ever abandoning our complex humanity and undeniable fragility.”

Hospital by Sanya Rushdi

“Hospital is an unflinching, insightful and delicately wrought work of autofiction that brings devastating lucidity to the often-opaque realm of mental health. Drawn from Rushdi’s own experience with psychosis, it is a novel that bucks the classic tropes and cliches, eschewing sensationalism and sentimentality in favour of an invitation to meaningful engagement and understanding.”

“Through her spare, honest words, deftly translated from the Bengali by Arunava Singha, Rushdi’s ordeal becomes our own. We descend into psychosis with the narrator, acutely feel her disconnections and institutional indignities. We come to question notions of “illness” and “treatment”. There are no jump scares, just the ineluctable clarity that demands we remain in the moment with something we find deeply uncomfortable.”

Abandon Every Hope: Essays for the Dead by Hayley Singer

“Few of us will grapple with a thanatography (an attempt to write death), few of us will do so with the brutal, confronting compassion that Singer does in Abandon Every Hope: Essays for the Dead. Experimental and jostling in its use of poetic, lyric, academic and reflective writing styles, this book grapples with the industrial meat complex, from slaughterhouses to cannibalism and beyond.”

“These fragmentary but, ultimately, coherent essays insert themselves into consciousness, long after the time required for their reading. Notwithstanding the gruesome, and sometimes gruelling, subject matter, this is a work that rewards bearing witness, a book where attention and looking – looking and looking and not looking away – offers the reader the opportunity for transformation and agency and, perhaps oxymoronically, hope.”

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright

“Fierce and gloriously funny, Praiseworthy is a genre-defiant epic of climate catastrophe proportions. Part manifesto, part indictment, Alexis Wright’s real-life frustration at the indignities of the Anthropocene stalk the pages of this, her fourth novel.”

“That frustration is embodied by a methane-like haze over the once-tidy town of Praiseworthy. The haze catalyses the quest of protagonist Cause Man Steel. His search for a platinum donkey, muse for a donkey-transport business, is part of a farcical get-rich-quick scheme to capitalise on the new era of heat. Cause seeks deliverance for himself and his people to the blue-sky country of economic freedom.”

“Praiseworthy walks the same Country as companion novel, Carpentaria, published in 2006, and here, Wright demonstrates further mastery of form. Reflecting the landscape of the Queensland Gulf Country where the tale unfolds, Wright’s voice is operatic in intensity. Wright’s use of language and imagery is poetic and expansive, creating an immersive blak multiverse. Readers will be buoyed by Praiseworthy’s aesthetic and technical quality; and winded by the tempestuous pace of Wright’s political satire.”

“Praiseworthy belies its elegy-like form to stand firm in the author’s Waanyi worldview and remind us that this is not the end times for that or any Country. Instead it asks, which way my people? Which way humanity?”