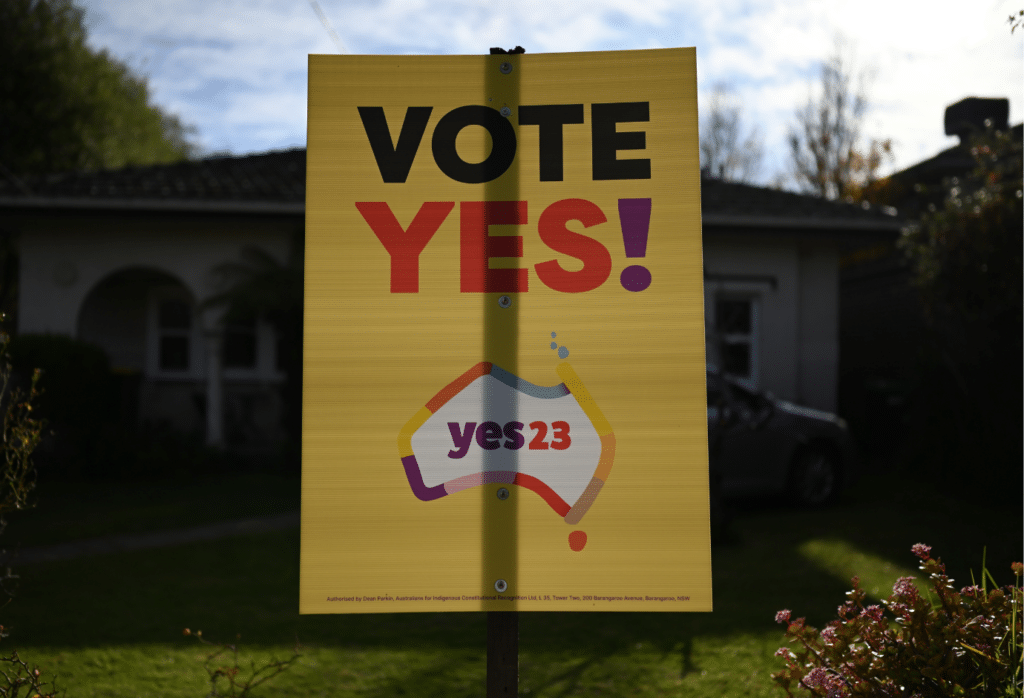

The referendum on the Voice to Parliament will take place on Saturday, October 14. The official campaign for the referendum is now underway, with Australian music legend John Farnham lending his song “You’re The Voice” to the yes campaign’s newest advertisment.

At the referendum, Australians will be able to vote “yes” or “no” to the question:

“A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

There is a lot of information out there about the referendum and the Voice – and it’s coming from all sides of politics. Here, we’ve taken some of the most common myths and misconceptions about it and broken down the facts.

The Voice would have veto power and override government

This myth is not based in fact. The Voice is an advisory body that would provide representations to the parliament and executive government on matters relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The Voice would have no power to create, amend, or stop legislation from passing through the parliament.

It will amount to a third chamber of Parliament

This is not true. The Voice does not have any legislative power, and therefore doesn’t meet the definition of a parliamentary chamber. The Voice is simply an advisory body that would provide advice to the parliament, much like the productivity commission provides advice.

Malcolm Turnbull – who used the term “third chamber” to describe the Voice when he was prime minister – has since come out and said his use of that term was not correct, and he does indeed support the Voice.

There is no need to enshrine the Voice in the Constitution

If the Voice is enshrined in the Constitution, it means it cannot be abolished or altered at the whim of the government of the day, or without significant public scrutiny. As stated on the Uluru Statement from The Heart website, enshrining the Voice in the Constitution gives the government a “strong incentive” to work with First Nations people, and ensure their advice is heard. It also gives the Voice certainty, as the only way it could be abolished is if another referendum was held to do so.

Enshrining the Voice into the Constitution responds to the call made in the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017, and gives Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people constitutional recognition. Currently, the constitution does not mention Australia’s first peoples.

First Nations people don’t support the Voice

There is no single view on the Voice among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and there are indeed some high profile opponents to the Voice, including independent senator Lidia Thorpe, who has said she doesn’t support the referendum. Senator Thorpe has explained her stance – based on the “Blak Sovereign Movement” – in this recent article.

However, there are multiple examples of strong support from First Nations people for the Voice. The process behind the Uluru Statement from the Heart (which proposed a Voice to Parliament) involved dialogue with more than one thousand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, from all over Australia.

Meanwhile, recent polling suggests widespread support for the Voice from First Nations people, with two polls this year showing more than 80 per cent approval.

There is not enough detail

What has been laid out for us to read in the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Final Report sufficiently and comprehensively explains the principles on which the Voice will be based, which was created with the expertise of a Referendum Working Group.

We can also learn about these principles on the The Uluru Statement from the Heart website, which can help us understand how the proposed amendment to the constitution will give Parliament the power “to make laws with respect to the composition, powers, functions and procedures” of the Voice.

We already have access to information about the exact wording of the referendum, details about the Constitution amendment process, the Joint Select Committee’s recommendations, and even the solicitor-general’s advice on the legal soundness of the amendment.

The exact nature of what the legislative change will look like can’t actually be worked out at this point in time. This is because the legislation needs to be passed through parliament first, and go through a series of potential changes before it is instated.

It will give First Nations people more and/or special rights compared to other Australians

No, it will not. The proposed amendment in The Voice will not give “special rights” to anyone. The Constitutional Expert Group said that the amendment will establish a body that can make permanent representations to parliament and the executive, and that the Voice would not “change or take away any right, power or privilege of anyone who is not Indigenous”.

Currently, the constitutional Implied Freedom of Political Communication ensures that all Australians have the same right to make representations to Parliament.