Please note the below discusses rape and sexual assault.

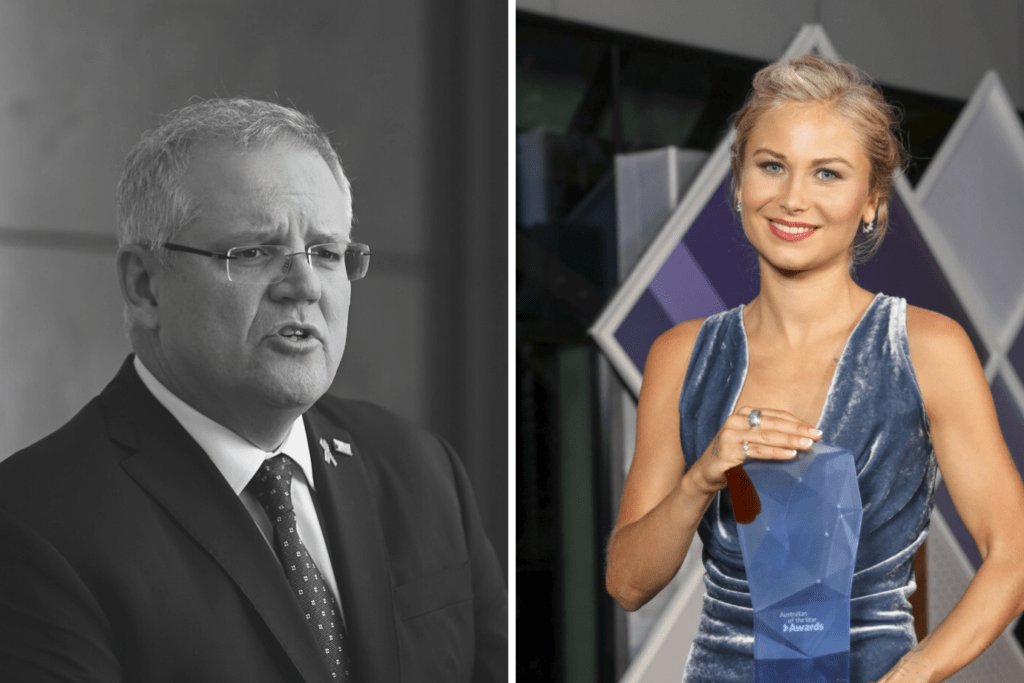

Australian of the Year and sexual assault survivor Grace Tame revealed this week that Prime Minister Scott Morrison whispered these words to her when she finished her powerful speech at the Australia Day award ceremony: “Well, gee, I bet it felt good to get that out.”

My blood boiled when I read those words. Not because they show how little the prime minister seems to care about sexual assault – I already knew that – but because it is a refrain I have heard again and again and again since I started speaking up about rape, and I’m tired of it.

At the heart of the prime minister’s comment is the fallacy that victims speak up about sexual assault purely to satisfy their own self-interest – whether that be catharsis, as the prime minister suggested, or attention or money, as so many others have suggested.

This insinuation has never made any sense to me. For me, disclosing my rape was the hardest thing I have ever done. The exposure and shame that speaking up brought into my life felt unbearable. Admitting that I had been raped – admitting to something that I had always been taught to be ashamed of – was truly, in many ways, harder than living through the assault itself.

This, of course, is how shame works. Our society’s constant shaming and victim-blaming around sexual assault leaves victims with the categorical belief that inviting violence into our lives is something we choose, and something we should be condemned for.

While we live in that world, it will never be the case that speaking up is purely an act of catharsis or reclamation.

Since I disclosed my rape, I have come up against near-constant expressions of this strange notion. People ask me: Do you feel relieved? Do you feel lighter? Is it just like therapy?

My answer is always the same. No, I do not feel relieved. My burden feels heavier than ever. No, speaking publicly about abuse is nothing like therapy. In fact, speaking publicly about abuse is the main reason I go to therapy. It’s the main thing I discuss in therapy. It is not something I do wholly for myself, and is for the most part something I do for others.

I speak publicly about abuse despite the panic attacks, the intense shame and bouts of depression it brings me because I know that doing so will make it easier for others to understand their own experiences and narrate their own lives.

The writer Rosie Price put this perfectly recently when discussing her novel, which details the aftermath of a rape that is based on her own experience. “People always ask me,” she says, “what it’s like to have your work be like therapy.”

“And I say: that’s not it at all. The work is the work. The therapy is the therapy.”

What Rosie is getting to here is hugely important: Our public actions, whether through writing or speaking, are professional endeavours. These are what we have chosen to dedicate our working lives to. They do not involve uncensored outpourings of emotion but rather considered, thoughtful, meticulously-edited and crafted pieces of work that we hope will generate better understanding of these issues. Put simply, as Rosie says, it is work.

This is why the accusations of self-interest are so grating to me – not only are they insulting in their nod towards self-indulgence, they seem to me to be a lazy way to devalue the work victims and survivors are doing in their field.

People say to me: “It must feel strange having people read your diary.” But this is not my diary. This is my job.

The same is true for Grace Tame. The implication that it must have been “good to get that out” completely and purposefully undermines the fact that her speech, and all the work that led up to it, were professional achievements on which she worked extremely hard and for which she should be congratulated and applauded.

Writing books about abuse is work. Giving political speeches about abuse is work. What’s more, it’s work that we do despite the impact it has on us emotionally, not because of it. The prime minister’s comments are just a way to undermine Tame’s talent and dedication, and it’s just not fair.