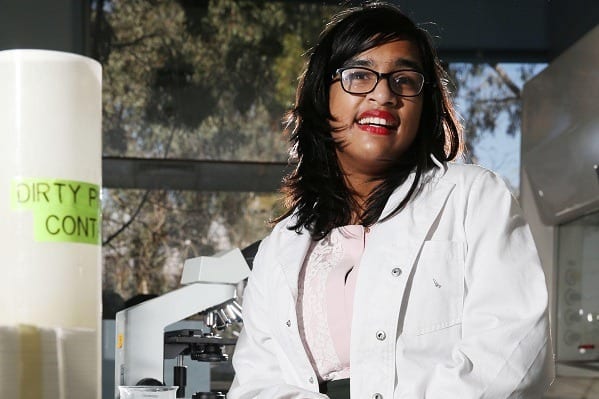

Jerusha Mather is a PhD student at Victoria University investigating barriers in strength training in adults with cerebral palsy. She is also a leading advocate for medical students with disabilities. Her aspirations and interests are in rehabilitation medicine. She has been fighting to get into medical school for most of her life. She really wants to pave the way for others like herself. In this piece, she writes firsthand about her experiences.

When I sat in a meeting with the dean of a medical school, it felt like I was having the same experience as Dr Shaun Murphy from the medical drama “The Good Doctor”. Only he’s a surgical resident, and I haven’t even started medical school.

I felt the same questioning of my abilities and skills. The same belittling remarks. I held the same doubt of whether I would belong – and make no mistake, I should belong.

I sometimes feel let down by people in this regard; it often feels like there is no one to run to for advice and counsel about my unique situation. But I also felt like there was something deeper going on, under the surface. Some narcissism. Some unrealistic perfectionism set by more traditional views that made these barriers in the first place.

But despite the many setbacks, I found the strength to keep going.

I made a complaint against ACER in 2016, the body that creates the Graduate Australian Medical School Admissions Test (GAMSAT). At the time, ACER was very difficult to work with. In my view, they still are.

I initially thought that if I could get the accommodations I needed, I would pass the GAMSAT. I needed to pass this test to get into medicine.

ACER agreed to give me some of the accommodations I needed.

I prepared for the GAMSAT in 2017 during my undergraduate with a tutor who was a medical student at Melbourne University at that time.

In my preparatory times, my tutor and I could see that I was really struggling with sections 1 and 3 of the GAMSAT. These sections required handwriting and speed reading and not enough was done to compensate for my disabilities.

Telling the scribe what to write was extremely challenging because there is a significant amount of working out to be completed to successfully answer the question. There is also time running away from you. This type of working out cannot be done on a computer. And to add to the mounting pressure, you are not aware what is on the test. It is not like a university test or exam where you have a rough idea of what is coming at you. It is hard to prepare for. It is long and stressful.

It appears to me that ACER and medical schools are passing the buck on this matter. One is blaming the other and vice versa. And this is not really helping the situation. And the medical deans are playing side to all this.

There is also a discriminatory policy document in medicine called the inherent requirements created by the medical deans, which lists qualities that they think a medical student should have. The list is blatantly discriminatory. Even the recent one being made this year named inclusive medical education for students with disabilities is discriminatory. It lists reflective questions that they believe a student with a disability should consider before applying.

They do not offer a welcoming stance. They do not offer solutions. Nor do they talk about altering the selection criteria. This is the primary responsibility of the medical schools. But the medical deans should encourage this. They should do more to include students with disabilities especially consider changing their selection criteria.

My submission to the medical deans was neglected and I did not receive a positive response on changing their policy to make the language more appropriate and acceptable.

Some universities readily accept Indigenous students without a standardised test score and I think it is fair that they offer a similar entry scheme for students with disabilities that enable acceptance based on their individual merit and abilities.

I applied to James Cook University – one of the few medical schools in Australia that do not require a standardised test score. With all my accomplishments including completion of an honours in biomedical sciences, I still did not obtain a place. This was very disappointing and disheartening. As disability is lowly represented in medicine, I think representation needs to be increased. I think more needs to be done in this space.

The attitudes and culture in medicine towards disabilities need to change. The more diverse the profession becomes; the more inclusion and acceptance will happen. And this will impact patient care in a positive manner.

With support, assistive technology, and a flexible mindset, there are many specialties that a person like me can practice in (rehabilitation medicine, pathology, psychiatry, radiology, and pediatrics – to name a few). You never know the possibilities and value until you give someone a go – and hospitals are willing to cooperate and support the transition.

At this stage, I am more interested in rehabilitation medicine. I remember I volunteered in the rehab ward in undergraduate and really connected well with people on the ward. I have a passion for this kind of medicine – that is why I chose to also do research in this area. I am really enjoying helping people achieve their goals.

I am continuing this advocacy and will see where it leads. It is slowly changing, and I believe things will be better in time. I really want to change this through my story and pave the way for others. I will never give up.

But I wonder now: when will the medical schools accept a student like me in their course? When will they change the selection criteria to make it fairer and more accessible? Why are we still having this conversation?