Last week the US state of Georgia passed abortion laws that wind back some of the hard-fought reproductive rights won through America’s landmark abortion case Roe v Wade.

The new legislation restricts abortion once “cardiac activity” can be detected. Since this usually occurs at around six weeks of pregnancy – at which point many are unaware they are pregnant – the legislation effectively outlaws abortion.

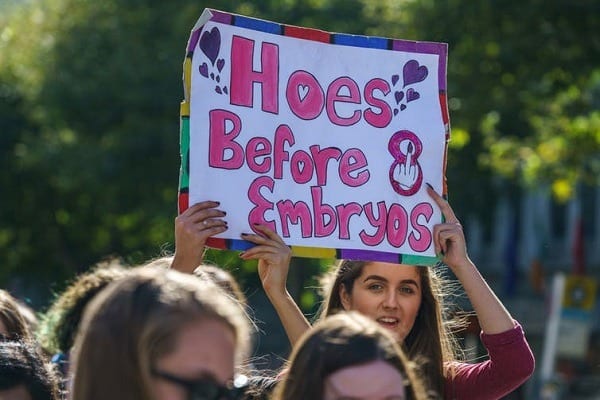

The introduction of these laws, and similar legislation across Republican-held states, has been met with fierce criticism from feminists, reproductive choice activists and medical professionals alike.

In a move reminiscent of her role in the #MeToo movement, Hollywood actress Alyssa Milano took to Twitter encouraging women to go on a “sex strike” in protest.

While the call to arms over reproductive rights is laudable, Milano’s approach is a deeply problematic one.

1. It doesn’t address structural issues

Milano’s response illustrates some of the worst tendencies of “white feminism”, with a focus on individual choice and failure to take an intersectional perspective.

The idea that women should deny men sexual “choices” frames the issue of reproductive rights in an individualised way. In this case, the “solution” to repressive legislation is individual women denying men (who may or may not be anti-abortion) partnered sexual activity.

Of course, individual action is both a necessary and powerful component of generating broader political change. But it’s largely unclear, in this case, how the proposed individual action translates into the collective mobilisation required to challenge political and legal institutions.

Access to abortion is a complex social, structural and institutional problem. Limited reproductive choice is rooted in legislation, other regulation,

and access to affordable health care. Likewise, access to abortion – and women’s experiences of accessing it – are shaped by a multitude of factors: race

and social

class. These underlying causes are unlikely to be shifted through a “sex strike”.

2. It frames sex in heteronormative ways

By suggesting that women avoid sex because they cannot risk pregnancy, Milano frames “sex” in limited and heteronormative ways.

“Sex” is constructed as involving penis-in-vagina penetration, reproducing the idea that only heterosexual, penetrative sex is “real” sex. This leaves little space for other forms of sexual expression – particularly those that are unlikely to result in pregnancy (such as oral sex or masturbation).

While clearly relevant to the issue of abortion, linking sex to a need to avoid pregnancy also implies that all women are in heterosexual partnerships with cisgender men, that all women are able to fall pregnant, and that only women can become pregnant, excluding trans and non-binary people.

Given the diverse repertoire of sexual acts available to us, it’s not clear why women (and others) should have to forgo ethical, pleasurable and wanted encounters. While the sex strike aims to regain bodily autonomy, this method of protest in fact further limits it, simultaneously perpetuating the “sex-negative” ideology that often underpins the logic of anti-abortion proponents.

3. It reinforces harmful stereotypes

Suggesting that women shouldn’t have sex until their sexual autonomy is regained reproduces the trope that women use sex as a bargaining chip, or tool to manipulate men. This reduces a complex structural and political issue to a tiresome “battle of the sexes”.

Women are stereotyped as the “gatekeepers” of sexual activity, who either say “yes” or “no” to men’s sexual advances, but never actively desire sex or initiate it themselves. Sex is positioned as something that women do to please men, rather than something they (gasp!) actively enjoy or find pleasurable.

This is concerning given that these stereotypes can be used to excuse sexual violence, or to place blame on victim-survivors. For example, survivors are often blamed for sexual violence because they have not fulfilled their role as sexual gatekeeper – that is, they didn’t say “no” clearly enough. At the same time, reports of sexual violence are often dismissed as accusations from a woman scorned. In other words, the sex strike reproduces many of the stereotypes that enable and excuse sexual violence, running the risk of further compromising bodily autonomy.

There is also an assumption that women are able to freely negotiate or refuse sex without consequence. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Most obviously, this occurs in cases of sexual violence through the use of force or coercion, or where submitting to a perpetrator may be the safest option in the moment. It assumes that women are situated in a world where the utterance of a “no” is heard in a meaningful way – and that saying “no” is safe in the first place.

Research also suggests that women can face enormous social and cultural pressure to comply with a partner’s sexual advances, meaning that refusing sex is not always straightforward.

Just ‘generating debate’?

Ultimately, Milano’s approach offers women a reductive level of “control”: sex or no sex. Encouraging women to forego sex in the face of restrictive abortion laws does little to transform how we approach sex and reproductive rights at the social, structural and institutional level.

Milano has defended her sex strike on the basis that it has generated widespread public debate about the issue.

At best, this “debate” distracts from the collective political action and structural change needed to truly challenge threats to our reproductive autonomy. At worst, it actively reproduces some of the conditions it seeks to disrupt, with the potential to exacerbate harms to already vulnerable and marginalised groups along the way.

Bianca Fileborn is a Lecturer in Criminology at the University of Melbourne. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.