The promised funding to build 75 new women’s refuges in NSW will double current capacity. This accommodation and support for women, children and pets in urban, rural, and regional areas will potentially save lives and importantly, will help deliver much needed services to these communities. However, scant detail exists on the design of these buildings that will need to provide safety, security, and dignity.

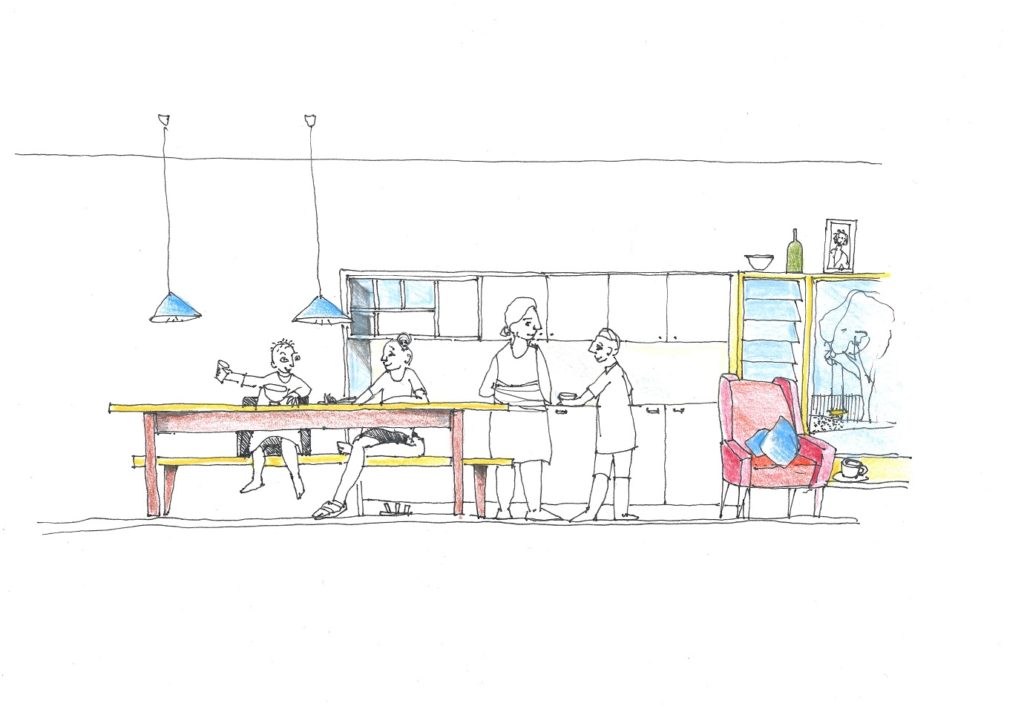

The NSW government suggests a “core and cluster housing” type is preferred. This housing type – self-contained accommodation units (clusters) with a separate administration office (core) – provides privacy and a sense of home to families who are allocated their own “house” with access to a communal kitchen for larger gatherings, laundry, and gardens.

The central core contains offices for the support team, consultation rooms and activity spaces. This housing type is radically different to the more common “congregate” housing type, where families are allocated a bedroom within a large house, sharing kitchen and bathroom facilities. However, it requires more land area, more construction, more security, and eventually more maintenance to maintain the landscape and units. Location of vacant land for refuges will be difficult in urban and suburban areas of need. In regional and rural towns, there is plenty of space, but services currently do not exist.

Two examples of core-and-cluster accommodation exist in NSW, in Griffith and Orange. Both projects were completed in 2020, after many years of campaigning and hard-earned community support.

South Australia and Victoria are more advanced in the development of core-and-cluster refuges, with several examples built in the last five years. Research on the success of this ‘new’ housing type suggests that children benefit the most. The independent units reduce children’s exposure to other families’ trauma and the sense of insecurity of being in a new unfamiliar environment. Families’ daily routines are less disrupted, and children can choose to interact with others in child-focused areas.

However, many women who need refuge do not have children, are older women with grown families, or are women on temporary visas who have few options and have experienced isolation and abuse. The quality of space for those working with and those experiencing trauma is important.

For some, independent living arrangements will be ideal, but for others being a part of a supportive community is needed. A one-size-fits-all approach to the proposed refuges will miss an important opportunity to improve on how we currently deliver safe accommodation.

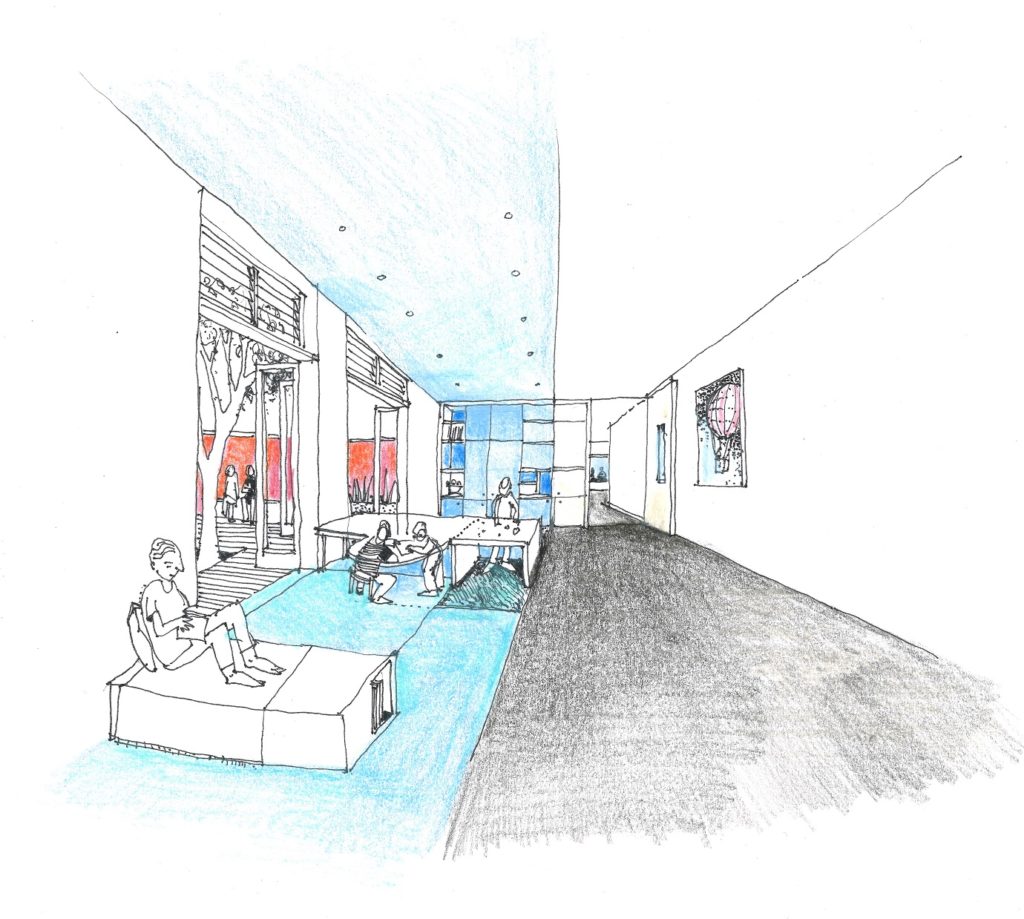

There are simple, sustainable design strategies that can maximise the impact of these new refuges, informed by the lived experience of those who use them. For example, good landscape design has immediate and advantages for both residents and staff and can be provided at relatively low cost. Sensory gardens and children’s planting areas can be integrated on-site, with therapeutic benefits for everyone. In-between spaces, like window-seats or study nooks, enable users to be social without having to be central, important for those who have experienced trauma, and for those who need time to heal, but also need to connect.

Maximum noise-control, access to daylight and natural ventilation is vital to maintain calm within the refuge environment and is essential for healing; creating a sense of place and connection to the landscape, shown to be important in building a sense of hope. These strategies are not expensive to integrate, and provide additional thermal performance, reducing running costs for service providers.

All refuge building types, including existing ones, can benefit through good design. Strategies that address environmental and social sustainability will improve the experience for those using the refuge and will go a long way to improving the stigma that surrounds refuges in general. We cannot afford to build 75 new women’s refuges without the wealth of experience that service providers and those who have used them offer. To ensure the success of the new refuges, we need to co-design and collaborate, and not accept restricted choices.

My research outlines architectural and design principles that provide positive sustainable living environments. I visited eleven refuges in the Greater Sydney area, interviewing providers and residents to understand the impact of refuge buildings on their daily lives. This research looked deeply at architectural differences between core and cluster versus congregate accommodation and their challenges. The resulting publication of a design guide for refuge accommodation outlines key principles to assist those working towards remodelling or designing fit-for-purpose accommodation.

Well-designed built environments empower parents, support children’s needs, facilitate healing, rebuild a sense of dignity and allow staff to focus on providing survivor-centred advocacy. If good design is only for the privileged few, then what good is it?