A new Greta Thunberg biopic has drawn criticism from those who don’t see the value in the stories of young lives. But children’s voices matter — and Thunberg’s is potent, writes Kate Douglas, from Flinders University in this article republished from The Conversation.

When a young celebrity writes a memoir or has a biography written about them, a common response is: they are too young. This child or adolescent cannot possibly have lived enough of a life, or have a useful perspective. Their story cannot be instructive enough to be valuable to others.

This point of view reveals the weight of expectation around public life storytelling. We too often dismiss the valuable contribution children make to politics and culture.

This week sees the release of the biographical film I Am Greta, directed by Nathan Grossman. The film follows Thunberg across 2018 and 2019, as she became known to the world. It reflects a close collaboration between Grossman and Thunberg, and the access he had to her life during this time.

I Am Greta has inevitably raised some eyebrows. Thunberg always does. Critics have suggested that we do not get to know the real Greta; Grossman keeps too much distance; he does not adequately delve into Thunberg’s childhood or family to explain the origins of her activism.

Such critiques reflect a rather narrow perspective on how biographical storytelling works. I Am Greta, like many contemporary life stories, does not conform to the “great man” model for biography, where history was thought to be understood through the life of men with political or colonial achievements. As new biographical subjects are chosen, so are new ways of telling their stories.

In choosing not to centre on Thunberg’s family and early life, I Am Greta defies genre expectations. The film centres on Thunberg’s voice, illuminating her words and her image at a particular moment in history. The focus is not on who inspired Thunberg to acquire knowledge, but how she — a young activist — developed these interests independently.

A rich history

Children and young people have been engaging in life storytelling for centuries. We just haven’t been paying enough attention. As Anna Poletti and I found in our research, there are many examples through history of young women writing politically-engaged autobiography.

Young English housemaid Elizabeth Parker embroidered her life story of cruelty and abuse in a cross-stitch sampler in 1830. This was the only way she could tell it.

Ukrainian-French diarist Marie Bashkirtseff wrote in her diary every day from age 14 until her death from tuberculosis at 25 in 1884. Hers was an ambitious social commentary on middle-class life.

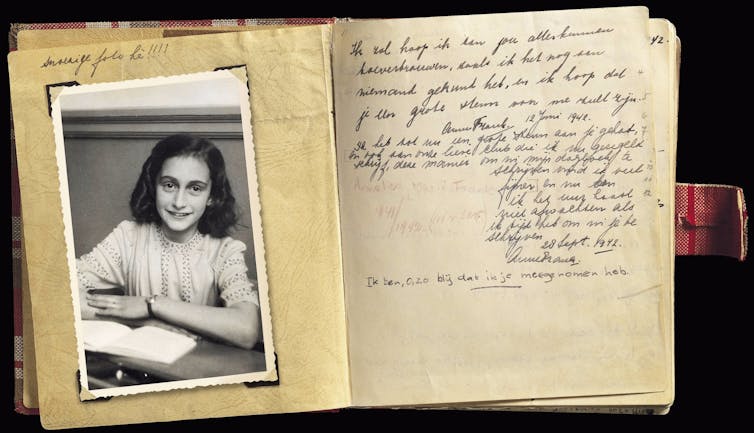

Anne Frank’s Holocaust diary was the precursor for Riverbend who blogged the Iraq war. Both Malala Yousafzai in Pakistan and Bana Alabed in Syria have been compared to Anne Frank with their diaristic recounts of war.

When we give attention to young people’s stories, it shows respect for their lives. Children are not just adults-in-waiting: their experiences and voices are significant in themselves and worthy of our attention.

Reading young people’s stories recognises their citizenship and the vital role children play in the political world.

‘A spokeschild’

In I Am Greta, we meet Greta on the steps of Swedish parliament, complete with the now famous homemade sign, protesting global warming. She is a lone figure, but not for long.

In this opening scene, Thunberg’s words are juxtaposed with those of adults. We hear the voices of politicians; of adults passing by who ask her what she is doing and why she isn’t in school. These moments signal the film’s focus: the contrast between Thunberg’s voice and those of the adults who condescend or criticise her.

I Am Greta asks us to think differently — not just about Thunberg, but about children’s voices more generally. Thunberg’s father, Svante, speculates that due to her photographic memory, Greta likely knows more about climate change than 97% of politicians. Such knowledge is possible.

Those who doubt Thunberg’s authority to speak on these issues most commonly argue because of her age, she cannot possibly be educated enough on these issues. Other critics suggest she is her parents’ puppet. She is often criticised for being an instrument of left-wing media.

Similar accusations have been made about other young female activists like Yousafzai, Emma González, Isadora Faber, and Bana Alabed.

When Yousafzai rose to prominence, critics referred to her as “the darling of Western media”, and “a tool for political propaganda”. Like Thunberg, her activism was assumed to be advancing her father’s politics and career.

Activists like Yousafzai and Thunberg are symbolic of rebellion, reconciliation and the complex spaces in between. Neither Yousafzai nor Thunberg ever intended their stories to become “master narratives”. Their activism is not an attempt to dilute the experiences or stories of other children, quite the opposite. Both have centred their careers on making connections with other young activists across the globe.

Young activists find themselves at the coalface of difficult histories and debates. They are writers and public speakers. But they are also children who become a consistent focus for the media. This media is not always kind.

The criticisms levelled at young activists reveal the mixed feelings society has around children’s voices and their capacity to act meaningfully when it comes to social change. Why does it come as such a surprise that children can hold knowledge and perspectives that are culturally and politically valuable?

As Thunberg speculates, international leaders talk a good talk when it comes to being inspired by her. They invite her to their castles and palaces, sites representing the kind of opulence and over-consumption Thunberg denounces.

They profess a commitment to change, but the change never comes. Thunberg understands her position as symbolic of the future, as a “spokeschild” who helps leaders improve their own appearance.

Condescending adults

I Am Greta shows multiple incidents where powerful adults are condescending, awkward or dismissive of Thunberg. Donald Trump and Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro are amongst the more vehement critics of Thunberg, but there are many others.

And there are others again who damn Thunberg with faint praise. The French President Emmanuel Macron, in patronising tone, asks, “You read a lot on climate?”

She meets Arnold Schwarzenegger, whose presence pales in light of Thunberg’s. She speaks intelligently at length, but Schwarzenegger simply repeats her final statement — “we need to join the dots” — as if lost for words.

Delegates at the 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference where Thunberg offered a powerful oration, seem adolescent in their desire to take selfies with Thunberg. There is nothing subtle in the film’s approach to this role reversal.

Thunberg convincingly argues she has little choice but to speak publicly. She equips herself with sophisticated knowledge and trusts science.

She speaks readily about climate change because leaders do not.

An early telling

In I Am Greta, handheld camera shots bring us intimately into Thunberg’s life. We see her alone, reflecting; starting small, thinking big.

Being in the public eye triggers her anxiety, but so did her knowledge of climate change — when she first learnt of the enormous problems the world was facing, she could not eat, sleep, and would not even talk.

We see her sensitivity and quirky vulnerability. Thunberg argues that being on the autism spectrum allows her to “see through the static” and acquire deep knowledge quickly and astutely.

Perhaps it is confronting for some to imagine it is a young, neurodiverse woman who can show us the way to a better future.

I Am Greta represents an early version of Thunberg’s life story. Thunberg herself has readily circulated parts of her story through social media. There have been a plethora of literary and media representations of her. There is a biographical picture book. There will be more to come. This is not unusual now.

I am Greta reveals how young people’s stories and perspectives might be received generously and potently to promote change.

I Am Greta is in cinemas now and will stream on DocPlay from November 14.

Kate Douglas, Professor, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.