Before Elyn Saks’ The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness, Esme Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias, and Kristina Morgan’s Mind Without a Home: A Memoir of Schizophrenia, there was Anne Deveson’s Tell me I’m here – her 1991 memoir about her eldest son’s tormented struggle with schizophrenia.

I’ve often wondered why women seem to be the major creators of memoir — especially about mental disorders and their tragic impact on families. Perhaps it has something to do with their intuition for love and care — the sheer will-power of their capacity to give love, often unrequited and unreciprocated, and the rigorous strength they display within the hidden, domestic confines of the home.

Perhaps this is why Veronia Nadine Gleeson’s deft adaptation of Deveson’s book worked so well on stage. Under Leticia Cáceres direction, the play stars Nadine Garner as Anne, a dynamic yet sensitive mother of three. Her eldest, Jonathan, played brilliantly by Tom Conroy, suffers a cerebral hemorrhage at birth. He is kept in an incubator for days. Anne is unable to hold her newborn, her first-born, during that period.

Three medical professionals in white lab coats appear, foreshadowing the life Jonathan would endure. His life is ear-marked by their intervention, or more precisely – their utter lack of solution. These suggest two emergent forms of malevolence on the horizon — Jonathan’s illness, and the medical field’s harrowing ineffectiveness.

Anne narrates the story, year by year, month by month, and the slow agony of Jonathan’s psychosis. He cries excessively as a child. He mutters incoherent statements.

He leaps onto the family dining table. He suspects he is being tracked by ‘The Russians’. By the time the word’ schizophrenia’ is uttered on stage for the first time by a medical professional, the impact has already been felt.

It’s the 1970s. Nobody seems to identify the origin points for Jonathan’s hyper-sensitivity.

The moment the play begins, a propulsive energy drives the narrative forward — there is hardly ever any point in which to catch your breath as an audience member.

Gleeson has managed to transfer this difficult memoir onto the stage with remarkably deft theatrical language. The passing of time is so carefully discerned, the moving pieces of furniture swiftly shifting the location of the drama from home to hospital to home.

The white walls and built-in bookshelves exudes the sense of space that comes with houses of a certain milieu. In some ways, Anne has much to be grateful for: blooming professional life, compliant younger children, comfortable house. As Jonathan grows, so does the severity of his demons.

Because the set never changes, the audience become heightened to the relationship between Jonathan’s corporeal limits and the house where his psychosis manifests. Dinners are ruined by his anarchic energy. His younger siblings, Georgia (Jana Zvedeniuk) and Joshua (Raj Labade) are cast in an almost unbearably sympathetic role.

We hear snippets of Anne’s life outside the home. She travels to countries inflicted by conflict and humanitarian crisis, to Kambala, to Somalia, taking jobs overseas “because it helps.”

The home is her war zone. The domestic female body of the mother has become the place of destruction and desolation. Jonathan’s soul is entrapped in his body, this condition which has no release, no cure. For Anne, the entrapment she feels as a mother and working professional is confounding too.

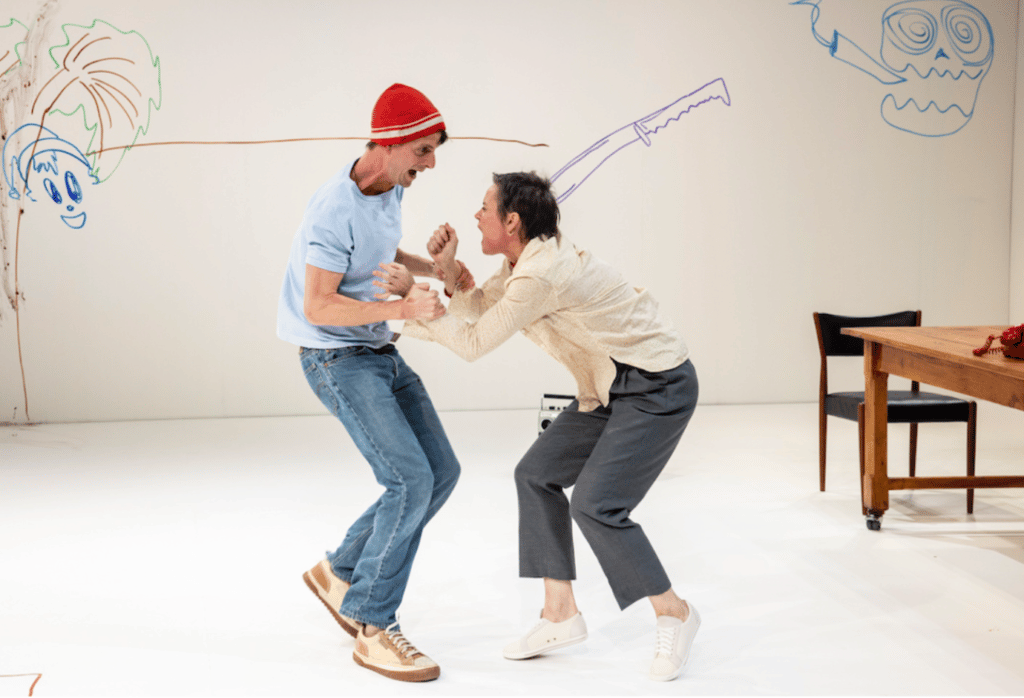

The source of dramatic movement comes from Conroy’s powerful, acute portrayal of Jonathan, who manages to reproduce the convoluted drama that unfolds inside a schizophrenic mind through agile, pointed physical movements, and the manic drawings he makes around the floor and walls — seemingly random lines, boxes, shapes, faces, swirls.

His drawings are always there, giving him a sense of spiritual omnipresence, especially in the scenes where he is not on stage.

The simple rearrangement of chairs into a row turns the family home into a hospital, shifting the set temporarily into an uncanny space.

Jonathan is admitted to hospital continuously over the course of years. He is released because the doctors cannot help him. They don’t have the legal powers to detain him. Some doctors tell Anne there is no such thing as schizophrenia.

The tale about a young man’s illness is also the tale about the illness and its visibility by those in power; by those in a position to change things.

By the end of the play, which culminates in a remarkable and startling finale, I didn’t know who to praise most — Conroy, for his extraordinarily lone and subliminal depiction of a young man’s paranoia, Gleeson for her victorious adaptation of Deveson’s memoir, Garner for her sustained emotional gravity (she was onstage for the entire play, sans interval) or Stephen Curtis, for his minimalist set decisions.

All of them contribute to making this play one of the most emotionally eviscerating seen on stage in years.