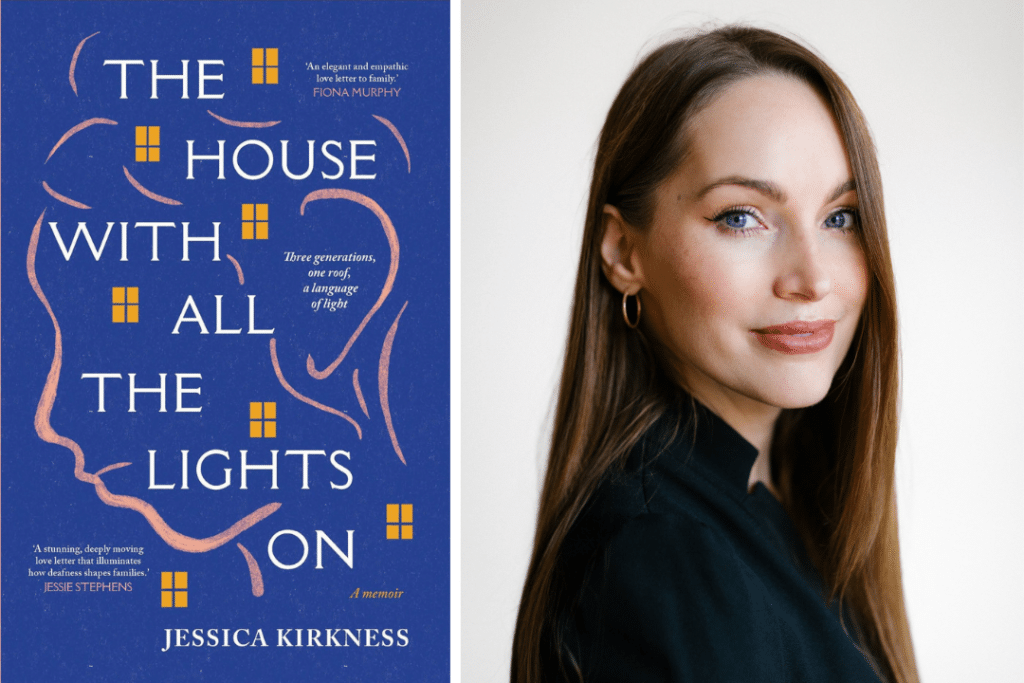

Jessica Kirkness has traversed the boundary between deaf and hearing cultures all her life. Her memoir tells the story of her grandparents who grew up deaf in a hearing world—one where sign language was banned for much of the twentieth century—and weaves in her own experience as a hearing child in a family that often struggled to navigate their elders’ difference.

The House With All The Lights On by Jessica Kirkness is published by Allen & Unwin and available now from all good bookstores or online.

Read the extract below.

Prologue

When I told my grandfather he was dying—translating the doctor’s prognosis from English into sign language—he smiled and shrugged his shoulders. ‘I’ve had a good, long life,’ he said. With my hands, I explained that he was in multiple organ failure after a cardiac arrest, and that he’d been unconscious for several days. His condition was critical. Grandpa nodded, moving his gaze between me and the white-haired physician standing at his bedside. Once we were left alone, Grandpa took hold of my fingers and squeezed them tight. His face was calm, steady.

It made sense that I’d be the one to deliver this news. Having studied Auslan—Australian Sign Language—for a few years before- hand, my signing skills were the most developed and, with the exception of Nanny, Grandpa understood me best. My mum and Uncle Ray were drained both physically and emotionally after months of keeping vigil in various hospitals and eventually a nursing home. And my grandmother, being deaf too, couldn’t have interpreted for him if she’d wanted to.

Grandpa had been sick for many years. His chronic emphysema meant he was often carted in and out of emergency departments.

Before his final stay in hospital, he could barely walk, and we pushed him around in a wheelchair Mum bought on eBay. On New Year’s Day Grandpa woke up unable to breathe, and an ambulance was sent. He was monitored for heart troubles that weren’t improving. We had five months with him after that. He never returned home. In that last stretch, my family shared the load, organising between us that someone be present whenever possible to ensure that Grandpa had an advocate. Often, hospital staff had no clue how to interact with him despite the communication tips my mother plastered on the walls of each institution. ‘Melvyn Hunt is DEAF,’ her handwritten signs read. ‘He cannot hear you even if you shout.’ We grew tired of reminding people to get his attention before speaking, to look at him, or to use the pens and pads of paper we’d

left so that he could understand and respond.

The combination of age and language barriers meant that his care was often compromised. Though Grandpa had excellent English, medical personnel could rarely understand his voice, and he struggled to follow the rapid-fire movements of their lips.

One night, early in his hospital stay, he had two blood transfusions without knowing what was going on. By the time I arrived in the morning he was wild with panic, vomiting blood and begging for answers. Nobody had explained what was wrong or why he’d needed the transfusions. He could only watch and wonder.

Having failed rehab by late March, he was sent to an aged-care facility, and in late April he was rushed back to emergency.

His death didn’t blindside us. It was neither sudden nor unexpected. We had another three and half weeks with Grandpa after the heart attack, for some of which he was lucid and even joked with the nurses in the ward. All of us—Nanny, my parents, my siblings, my cousins, Uncle Ray and Auntie Ruth—watched on as he slipped in and out of consciousness, waking for occasional sips of lemonade and beer that we’d snuck onto the premises.

Those familiar with Deaf culture talk about the phenomenon of the ‘long Deaf goodbye’, where the ritual of farewelling one another tends to stretch on and on, far longer than in hearing interactions. Grandpa was unhurried in saying goodbye to his family. I like to think he was holding onto us just that little bit longer, savouring those last embraces and tidbits of conversation.

It has taken me many attempts to say goodbye. To me the process feels eternal—bottomless and unrelenting. Grief, as Joan Didion writes, ‘has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.’ Three years have passed since Grandpa died, and it has taken many such paroxysms to make any sense of the loss. There is no instrument to measure the mark a person leaves, no salve to remedy the ache. My grandfather’s life was both ordinary and extraordinary—his deafness was so exquisitely misunderstood that every part of me felt summoned to translate.

_______________________

1.

If I were to tell you our story in sign language—the story of my grandparents and me—I’d begin with a single finger touching my chest. My hands would form the signs for ‘grew up’ and then ‘next door’, a flattened palm rising from my torso to eye level, followed by my index finger hooked over my thumb and turned over at the wrist like a key in an ignition. I’d use the signs for ‘my grandparents’: a clenched fist over my heart, and the letter signs ‘G, M, F’ to represent ‘grand-mother-father’. Then, placing two fingers over my right ear, I’d use the sign for ‘deaf’ to refer to them, and to describe myself, I’d use ‘hearing’: a single digit moved from beside the ear to rest below the mouth. I’d sign our closeness by interlocking my index fingers in the sign that doubles for ‘link’ or ‘connection’. By puffing air from my lips, squinting my eyes slightly, and rocking my looped fingers back and forth, I’d place emphasis on the sign, the duration, direction and intensity of its delivery giving tone and shape to the meaning it makes.

Like the opening montage of a film, I would set up the space before my body, carving a visual representation of the dual-occupancy home where I lived beside Nanny and Grandpa for most of my life.

With my hands poised as though ready to play a piano, I’d sculpt a diagram of our long, narrow house, showing its shared roof and the single wall that separated my place from theirs. By turning my hands with the thumbs facing upwards, I’d slice through the air, two-thirds of the way through the structure, to mark out the four- bedroom residence that belonged to my parents, my sister, my brother and me. By repositioning my hands to the left and pointing to the remaining third, I’d show you the semi-detached granny flat where Nanny lives to this day.

In Auslan, stories unfold like moving pictures, with images sewn together in an art similar to cinematography. Narratives are rendered through a sequence of different frames, shots and angles conveyed by the signing body. A signer can zoom in or zoom out of aspects of the action by employing different visual and spatial tactics. Within seconds, a fluent signer might weave between a ‘bird’s-eye view’, giving topographical information about the place depicted, and then, through shifting the body, will become the character in the scene as they open a door, for example, or rifle through a filing cabinet. Much like a panning or tracking shot, movement functions in these frames by directing the viewer’s attention. Particular types of movement can also indicate shifts in character and point of view: where the body takes on a new set of idiosyncrasies including stance, gaze and range of facial expressions.

But I cannot write this book in Auslan. The language, with its own distinct grammar and syntax, has no written form. There is no accurate way to represent it on the page. Besides this, it’s only in recent years I’ve known how to sign some of its parts at all. I am not a native signer. English is my first language, and dominant tongue. To tell our stories, I must write them down. I cannot do them justice any other way.