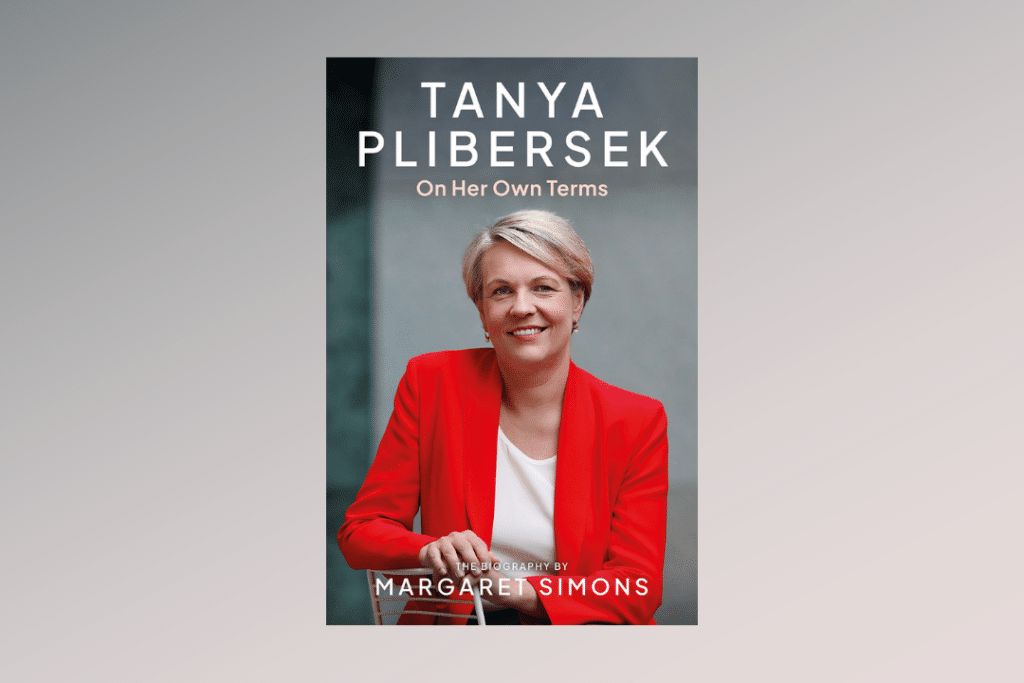

Elected to federal parliament aged just twenty-eight, Tanya Plibersek has lived almost half her life in the public eye, and is the longest-serving woman in Australia’s House of Representatives. In the new biography, Tanya Plibersek: On Her Own Terms, award-winning journalist Margaret Simons draws on exclusive interviews with Plibersek, her political contemporaries, family and close friends to trace the personal and political strands of this modern Australian story. Below is an extract from the newly released book.

Tanya Plibersek has a memory from when she was very young. It was the middle of the night. She was awakened by one of her mother’s friends arriving in distress, in fear for her life. Tanya remembers her mother supporting her friend. She realised that night that not all homes were as safe and loving as her own, and that some women had good reason to fear their husbands. It had a profound impact.

She recalls: ‘I found it really shocking, because my parents had a very loving and equal relationship. It was traditional in some ways, because my dad was the breadwinner and my mum was the homemaker, but they loved and respected each other and all the important decisions they made together.’

As she grew older, there were other cases – women with violent, sometimes alcoholic husbands who seesawed between trying to care for their partners and running away to keep themselves and their children safe. There were few places to turn. The police were mostly not helpful, and this migrant community did not necessarily trust the agencies of government. Rose, Tanya’s mother, took the women into her home, and tried to help over many years.

Tanya draws a connection between her growing awareness of her mother’s attempts to help her friends and her own time as women’s officer at the University of Technology, Sydney. Later, as a frustrated junior research assistant at the NSW Office of the Status of Women, she tried to make a difference to women at risk of violence and left because she concluded it was not possible under the state Liberal government.

This was the work of her entire adult life – the area she knew best and felt most deeply about. As Minister for Women in the Rudd and Gillard governments, she got her chance to make a difference, and she used it.

For years, overworked, often traumatised women in fragmented and underfunded groups had been battling to help the victims of violence. They worked in women’s refuges, in legal services, in police forces, in hospitals and public health – but there was little coordination and no coherent government narrative. Different groups were often forced into competition with each other for scarce funding.

Properly conceived, domestic violence was the biggest health, human rights and law enforcement issue in the nation – and one of the biggest economic issues – but government action tended to focus on law enforcement, and that, together with the funding of refuges, was mostly a matter for the states.

In opposition, Labor had committed to developing a long-term plan to combat violence against women, and to establish a National Council on Violence Against Women and Their Children that would report to cabinet. Plibersek was clear from the outset that what was needed was a conceptual shift – for violence against women to be accepted as a national crisis, needing sustained attention at every level of government. She brought to the task the networks and perspectives she had formed over many years.

Kevin Rudd had a personal commitment to the issue of domestic violence. In 2008, he gave a passionate keynote speech at a White Ribbon fundraising event. It was time, he declared, to have a national conversation and turn the terrible statistics around. International research had established conclusively that the chief underlying cause of violence against women was gender inequality. But for a prime minister to state this in such rousing terms was new, and a landmark.

White Ribbon was in theory composed of men who wanted to combat family violence. In fact, much of the organising was being done by women, notably the cofounder, Libby Lloyd. Plibersek handpicked Lloyd to chair the promised National Council, which had been reconceived as an engine of fundamental change.

The other members of the new council, chosen by Plibersek and Lloyd, included frontline domestic violence workers, journalists, public servants, academics and survivors of violence from across the country – mostly women who rarely hit the headlines, all of them toiling away in their respective areas. Plibersek charged them with devising a comprehensive, ambitious and systemic long-term national plan.

Lloyd recalls her work on the council as one of the most extraordinary times of her career. ‘I’ve never experienced anything like it before or since. How often does a minister bring together a group of people with expertise and trust them to get on and do the job, and give them all the resources and liberty to do it? We knew this was a moment in time, an opportunity that might not be repeated, and we had to seize it.’

Plibersek says today that she never doubted that government action could, and should, reduce violence against women. She regarded it as a problem analogous to getting smoking rates down, or stopping people from drinkdriving. It was not only a matter of personal responsibility. There needed to be strong laws, properly enforced, but also attitudinal change. ‘I can’t remember a time when I didn’t think that those two things had to go together.’

The national plan would have to involve all levels of government and touch on almost every portfolio. Lloyd thought it essential that the plan should outlast any particular government and asked for the opposition to be brought into the conversation. Plibersek told her, ‘I can’t do that work,’ but she gave Lloyd her blessing to start conversations across party lines.

The council released its report, Time for Action, in April 2009. It proposed that Australian governments should commit to a twelve-year plan, broken down into four three-year action plans. The plan was immense and ambitious, and ahead of its time in its understanding of intersectionality – the way in which men’s violence overlapped with other forms of discrimination and marginalisation caused by gender, ethnicity, Indigeneity and poverty. Central was the still politically radical assertion that the core cause of violence against women was gender inequality.

The Commonwealth released its response to the council’s report almost straightaway, with a commitment of $42 million to address urgent recommendations. These included the establishment of a new telephone and online counselling service (now known as 1800 Respect), the implementation of respectful relationships programs in schools, and the development of a social marketing campaign targeted at young people and parents.

Plibersek announced the launch of 1800 Respect on 19 July 2010. Just two days earlier, Gillard had called an election for 21 August. The Labor government had begun its painful final chapter.

While drama, tragedy and misogyny engulfed the government, however, the National Plan was implemented. New agencies were created and new programs rolled out. By the time Labor was defeated at the 2013 election, the first threeyear action plan was coming to its end, and the second, meant to build on those foundations, was about to begin. Although the Abbott government dismantled much of Labor’s legacy, the National Plan survived – or at least, the framework remained in place.

Under the new Coalition government, the women’s advocacy networks were caught up in an attempt to prevent charities from undertaking advocacy work, and they became riskaverse. 1800 Respect had at first been staffed and managed by the Rape and Domestic Violence Services Australia, an expert agency. But the Coalition’s social services minister, Christian Porter, limited its funding and then attacked it for supposedly not answering enough calls. The service was then handed over to Medibank Health Solutions, part of the insurance company Medibank Private. Calls were taken by non-specialists, who would refer callers on to domestic violence services, adding an extra step for women in crisis to negotiate before they could reach qualified counsellors.

Interviewed for this book, Plibersek argued that while the Coalition government had maintained the framework of the plan, it had undermined its intention. An auditorgeneral’s review, released in 2019, found that attention to planning and performance measurement had declined and was now ‘not sufficient to provide assurance that governments are on track to achieve the National Plan’s overarching target and outcomes’.

Nevertheless, much was achieved. The plan began a national conversation that remains underway. A national survey in 2021 found that Australians were more likely to recognise coercive control as a form of domestic violence, less likely to excuse domestic violence, and less likely to believe that women have a duty to stay in violent relationships for the sake of the family.

Social change of this scale and ambition is the work of ages. In the years since the National Plan was launched, the prevalence of intimate partner violence has remained relatively stable, and sexual violence has become even more common. But to see that as evidence of failure would be to misunderstand the scale of the challenge, the nature of far-reaching reform, and the patient persistence needed to achieve social change.

Today Plibersek regrets that she didn’t move faster, so that the plan was further underway by the time Labor lost government. But she points out that today, nobody suggests a national plan is not needed. ‘Support for these types of measures is much broader across the political spectrum . . . I think most people now accept that this is a legitimate and important area of activity for the federal government.’

Plibersek remains convinced that Australia can ‘massively reduce the incidence and severity’ of violence against women, but it will take a sustained effort over decades. ‘It cannot be done in a stop-start fashion and it can’t be done unless we are prepared to admit that gender inequality is the most significant factor in violence against women. And it requires bravery and leadership, because as soon as you talk about gender inequality, there’ll be someone pushing back and saying, “What about men?” This is the patience and persistence Plibersek says she learned from Jenny Macklin – understanding that policy innovation can be the work of a lifetime. Sometimes, it takes longer than that.

The paradigm shift that Plibersek achieved was to move violence against women from the sidelines of public policy to the centre. This is perhaps her single biggest contribution to public policy so far.