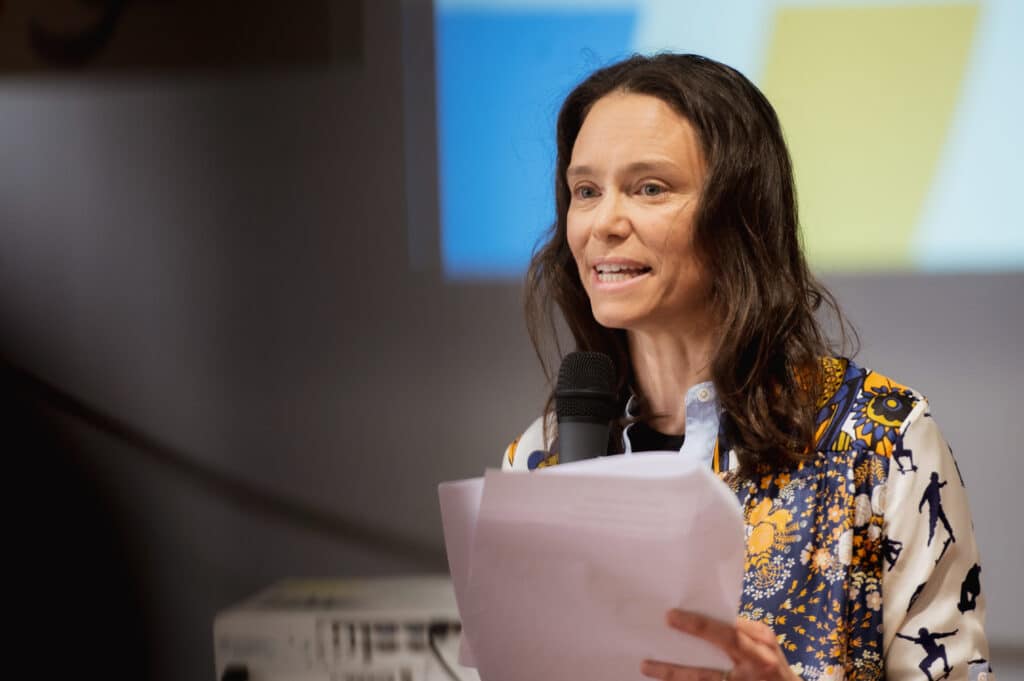

Sport can do extraordinary things for humanity, and no one knows this better than Jojo Ferris, the head of the Olympic Refuge Foundation.

Throughout her life, Ferris has witnessed how sport and the Olympic Games can transform lives, educate and empower, especially for women, girls and other marginalised groups.

Since 2018, the Australian national has headed the Olympic Refuge Foundation, which manages the Refugee Olympic Team.

More than 100 million people are displaced around the world, and every two seconds, another person is displaced due to the effects of war, conflict, climate and other humanitarian crises.

But refugees and displaced persons are people too – with hopes and dreams, weaknesses and strengths – which is why, in 2016, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) helped the Refugee Olympic Team compete in the Games for the first time at the Rio de Janeiro Games.

And this week, at the Paris 2024 Games, the Refugee Olympic Team is about to win its first ever medal, as boxer Cindy Ngamba guaranteed herself a spot on the podium overnight. Ngamba, the flag bearer for the Refugee Olympic Team, defeated Davina Michel in the 75kg women’s boxing quarter final on Sunday, meaning the team made up of 36 athletes this year will win its first medal since the team began competing.

We bring to you this Q+A with Jojo Ferris – what sport means not just to her, but to the people she works with around the world every single day.

Why is sport so important?

I think there’s an understanding in the general public about sport’s benefits for physical health, but I think the mental health angle is less understood. Sport provides a sense of connection and a place to belong. In Uganda, our Game Connect program led to a 90 per cent decrease in young people reporting depression and anxiety.

You must hear extraordinary stories all the time…

Yes, every day. One example is a coach who we work with in Uganda. He’s experienced extraordinary adversity and is now leading young people who have experienced significant violence and abuse – he’s able to relate and connect with them, and in return, he’s built his self esteem, confidence and leadership qualities. He’s now a role model for other young people who have had to flee their homes due to violence and conflict. It affects the whole community.

What is the biggest challenge of your work?

I feel really privileged to do this work, but also a sense of responsibility. One big challenge is to communicate and convince people of the importance of sport and physical activity in contexts of displacement. Of course, shelter, food, water, hygiene and security have to be prioritised but most situations of displacement are protracted./go on for years. People are not there for a day, a month or even a year. About 80 per cent of people who have fled their homes do not live in refugee camps. So, there is a real need to build a community, support mental health and create a sense of belonging. Sport can contribute to this in a significant way.

What do you want the broader population to know about sport for displaced people?

Barriers exist to refugees taking part in sport – it might be visa restrictions, it might be financial or it might be cultural reasons. If sporting communities can commit to the idea of opening up your sport and your sessions to refugees in your area, it could do amazing things. I often wonder in Australia, how many refugees have the average Australian spoken to? Have you ever introduced yourself, had a chat or invited someone over for a meal or to join in a game of sport?

How do you cope with hearing traumatic stories?

A lot of our program participants have experienced severe trauma. My view is that it’s better to know the reality than stick your head in the sand and keep the world in its current state. When I have the privilege of connecting with someone who shares a story with me, I feel so privileged that they were able to share that. It does affect me a lot, but I try to see it as a richness. I also practise gratitude every morning when I wake up – counting things I’m grateful for on my fingers.

What do you want to achieve through your work?

I’m a realist and I understand we can’t fix everything. When someone tells you that they’re carrying years of trauma, we can’t fix that. But can we hope for a better environment for them? Can we hope for their kids not to experience the same thing? Can we hope that they might get a day or reprieve or some enjoyment from our programs? Yes. And I have been called an idealist more than once but I think that if I can play a role in that, or at the very least be a listening ear, then that’s something. I want sport to be considered more seriously as a way to support and ensure young displaced people can thrive in their new communities. This means changing policy, frameworks and budget decisions so that sport is embedded as a crucial tool to support displaced people and their communities.

How do you teach people sport?

The real challenge is finding a way to reach people who are not getting the benefits of sport. We’ve got many different programs all over the world, which are tailored to the youth in that area. For example we work with communities in northern Bangladesh where 73 percent of women and girls are married young, and a lot of the husbands and families would never approve of them to be playing football or games outdoors where they can be seen by the community. So a lot of the sessions delivered there are using traditional games so they don’t need to go outside to participate. The girls said it’s the first time they’ve been invited to be part of something like this, and that they now have a support network in each other. So I feel very confident in the calibre of the program and the way in which it’s delivered which is a credit to our local partners there; Terre des Hommes, Breaking the Silence and Solidarity.

You travel to some extraordinary places for work. How does that benefit you?

When I travel and get out of my usual context, it creates space in my brain to think more creatively – you come at challenges in a different way. We go to “tough” places that may have security issues, but you always see those commonalities of parental love and the joy of play. In Jordan we went to a refugee camp where people have been living for more than 10 years – they’ve got rich cultures and shops and hairdressers and music. There’s no freedom of movement, but you still see the kids playing, the thirst for education, the pride in which they prepare a meal or prepare for a special occasion.

Where can we find you when you’re not working?

I try to start each day with a swim or yoga – it’s centring, clearing and reorienting. Living in Lausanne, Switzerland, I spend a lot of time with my kids, swimming in the lake or taking them ice-skating in winter.

What are you looking forward to at the Paris Olympic Games?

I am really looking forward to Paris – it’s a chance to demonstrate the role of sport on a big scale, and I’m hoping this will be the best performance ever from the Refugee Olympic Team. What’s not to look forward to? Especially in the state the world is in – this is an opportunity to bring more countries together than at the UN, in a demonstration of peace. That’s what ultimately excites me.

What can readers do to support your work?

Get behind the Refugee Olympic Team at the Paris Games; donate to the Olympic Refuge Foundation, and if you’re involved in the sporting community, make a commitment to opening your doors and welcoming refugees into your sport.