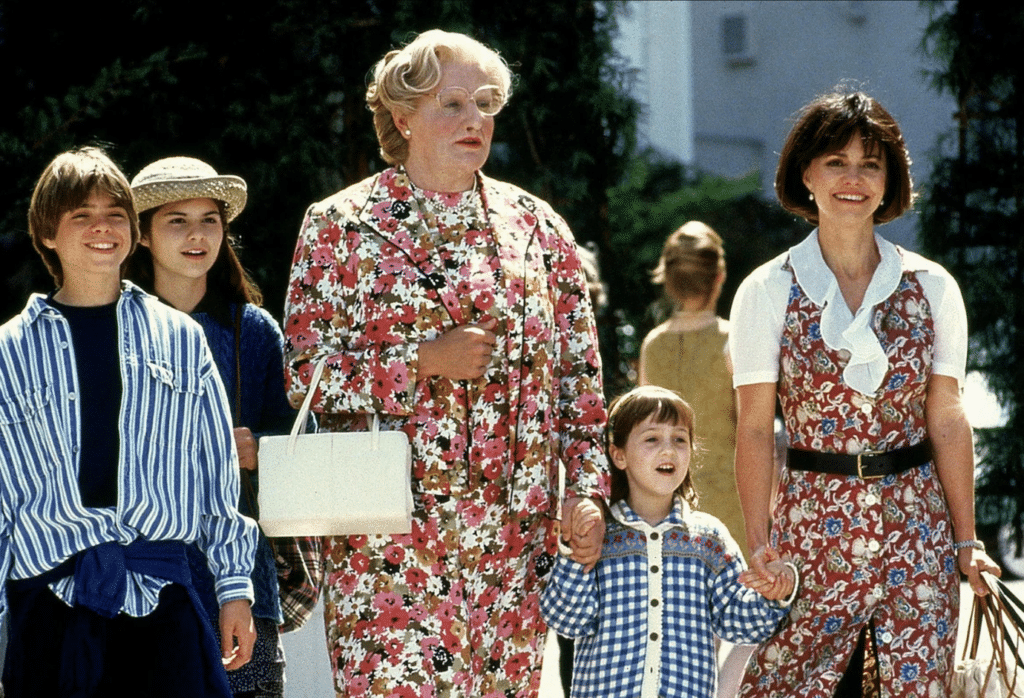

Jessie Tu is reviewing the classics of the 1990s to see how they stand up today. Below, she rewatches the 1993 Robin Williams hit, Mrs Doubtfire.

I’m not sure why Mrs Doubtfire is classified as a ‘comedy’ when it is actually a very, very sad film about children dealing with the divorce of their parents.

When Sally Field is called home by a very nosy neighbour and walks through her own front door to discover random children frolicking about and shaking their ass to House of Pain’s Jump Around, you’d think she had just stumbled onto a battlefield covered with armed militants — such is the weight of her shock and repugnance.

And then she gazes upon the worst sight of all — her middle-aged husband, Daniel (Robin Williams) dancing on their fancy dining table, donned in an oversized flannel and a baseball cap to the side, flanked by two teenaged boys (one of them is their son, Chris) — whose 12-year old birthday party is about to be murdered by the totalitarian anti-fun of their mother.

When Field (who plays the overworked, wearied, unrecognised mother of three, Miranda) pulls the plug of the sound system, killing the beat, the movie implodes. It’s as if the woman of the house has sucked all life out of the universe, like a black hole. She is a monster. A joy terminator.

When I was a child watching this film for the first time, I felt that same rush of deep, real hatred for her as I did recently, watching it on the film’s 30th anniversary. How dare she! The voice in my head cried. What a monster! The dad was just trying to make their son feel special! Why is she so cruel?

Which subsequently and very immediately moved her into the “team meanie” category in my head. In fact, none of the women in this film are painted in a charitable way.

After seeking a divorce right after the birthday party, Miranda gets herself a female lawyer whose shoulder-padded suit, blonde, permed bob and ammunition-filled smirk alone could make you squirm with a guilty conscious. The court liaison assigned to Daniel is an aged woman with a hard face and no sense of humour, the bureaucratic type that is out to punish irresponsible fathers and can’t even laugh at Daniel’s limitless voice characters. (This part of the movie has dated, sadly, and though I did burst into laughter, it was more of an awkward “god, this is pretty racist and wouldn’t track today” sort of noise).

Their eldest daughter, Lydia, is also written as being difficult. She’s mean to her father when she visits his new apartment after the separation, telling him his living conditions are ‘detestable’, and she is rude to him when she first meets him as Mrs Doubtfire – though, of course, she doesn’t know Mrs Doubtfire is actually her dad.

In fact, the whole deception conducted by Daniel in dressing as Mrs Doubtfire is played for laughs. The last to know the truth is always the wife.

This movie is a classic, there’s no questioning its place on our mantel of nostalgic items from the nineties. But what is it really a film about?

What does it mean to be a good father? What does it take to heal a broken family? And why does he have to transform himself into ‘the ideal woman’ in order to discipline his children, clean the house, make dinner, show love, and be tender and caring? Why couldn’t he do all those things as a straight cis male?

What does this film ultimately say about shifting gender roles? About how we love and who gets to police that? Beyond such questions, it’s clear that women, especially Field’s character of Miranda, is the one we’re supposed to hate. By the time the pair reconvene in court, Daniel has found himself a job, cleaned up his apartment, made it ‘child friendly’ — all by himself! — and is ready to be given equal custody of his children. But equal custody is not granted.

The mother is a monster — denying this poor man his children — his air. (“The idea that someone can tell me I can’t be with them, I can’t see them everyday…it’s like someone saying, I can’t have air,” he says.)

Despite the somewhat happy ending to this film, it still feels like a strike against women, against women who refuse to be married to man-childs — men who don’t share the domestic labour and child care and want a pat on the back when they can keep their apartments clean.

We’re clearly meant to sympathise most strongly with Williams’ character, Daniel — the flamboyant, vivacious, spontaneous man who can’t quite keep a steady paycheck because he’s too moralistic (recall the opening scene when he walks away from a voice over gig because “The fact that Puggie the Parrot has a cigarette shoved into his mouth is morally irresponsible… million of kids watch this show.”)

He’s the good guy! She’s the baddie. I’ve seen this film seven, eight times, mostly on television, when it was showing on Channel Ten on Friday nights when I was growing up. Each time, I was rooting for Daniel, hoping he’d win his way back into the family. I always detested Miranda for denying him his only source of happiness. Yet this year, watching it as someone who is closer in age to Miranda than the children, I found myself sympathising with the character who had it the hardest: Miranda. Of course she’d leave a man like Daniel if she could – a man who could never be serious with her, who tells her to ‘lighten up’ (every woman’s favourite instruction), and who accuses her of loving her corporate job too much.

This is the small profundity and joy of watching films from thirty years ago – canonic works that shaped us when we were younger. You watch it as a critically thinking feminist in adulthood, and you realise that so much of it was teaching us all small, nefarious lessons about men, women, and how we should feel about them.