It’s not common knowledge, but dementia is one of the leading causes of death for Australian women. So how do we look out for early symptoms? And if we’re experiencing memory loss and mood changes, should we worry?

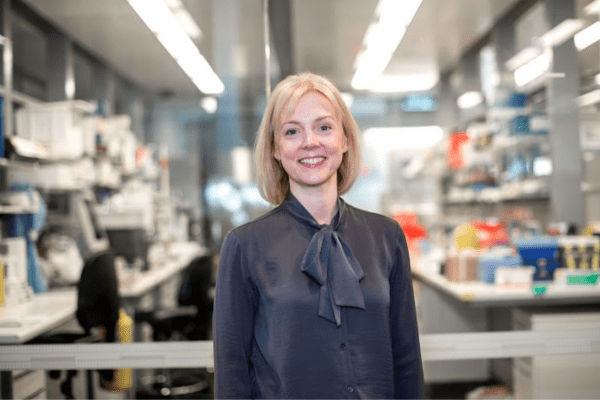

Associate Professor Rosie Watson is leading a team of researchers at WEHI (previously known as the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research) fighting to extend the life expectancy of Australian women. A clinician researcher with a background in geriatric medicine, she established a new lab focusing on dementia with her colleague Associate Professor Nawaf Yassi in 2019.

As a medical student, Dr Watson had a part-time job caring for older people in the community with the local council which “sparked a passion” in her. “I really wanted to support the older and more disadvantaged groups in society,” she shares.

Last February, that passion was realised when Watson received over $1.2 million dollars in federal government funding as Chief Investigator on an international project aimed at boosting the outcomes of dementia patients at The Royal Melbourne Hospital. The funding was part of the $5.5 million government package for ground-breaking medical research projects aimed at improving conditions in mental health, dementia, aged care, cerebral palsy and diabetes.

Watson is using the grant to translate scientific discoveries into dementia into real world outcomes, and this week, Women’s Agenda checked in with her to get a better insight into the disease, what we can do about it, and hopes for the future.

What sparked your interest in the diagnosis and management of dementia?

When I first started training in geriatric medicine, I was struck by how little we knew about dementia and how limited the treatment options were. It was clear this was an area desperately in need of more research and I really wanted to contribute to making a difference to improving the quality of life for people living with dementias and their families.

What are the early signs of dementia?

It’s unfortunately a common condition with devastating effects yet there are currently no disease modifying treatments. There are different types of dementia, and symptoms vary depending om the type. Broadly, some of the signs of dementia can include memory impairments, problems with concentration and thinking processes, word finding difficulty, personality or behavioural changes and difficulty with familiar tasks. It is important to consider medical conditions, medication side effects and depression and anxiety which can also impact cognitive function but may not necessarily be caused by dementia.

Why is diagnosing dementia early important? What do you want people to know about the process?

It is important that individuals have access to the appropriate assessment for dementia. This can be a difficult and lengthy process, particularly for people with less common forms of dementia. Symptoms of dementia can be caused by different conditions, some of which may be reversible such as medication side effects or depression. It is therefore important to raise concerns of changes in memory and thinking with your GP, who can screen for these potentially reversible causes. If further assessment is needed, the GP will refer you to see a specialist.

The diagnosis of dementia remains challenging and relies on assimilating clinical information. There is currently no single test to diagnose dementia. The assessment involves a comprehensive medical assessment and cognitive evaluation and frequently neuropsychology and brain scans.

Early diagnosis and improved awareness are the first steps in supporting people and their families in developing a management plan, which needs to be individualised and comprehensive. Part of the assessment will also establish whether there are potentially treatable or reversible factors such as depression or medication side effects which may be impacting a person’s cognitive function.

An early diagnosis enables a person living with dementia and their family access to crucial education and support in managing symptoms and planning for the future. This can include aids and services to optimise quality of life as well as considering legal and financial arrangements for the future, as the condition deteriorates. Early diagnosis will become more important as effective treatments are developed, allowing early intervention to minimise the impacts of the condition.

What is your lab currently working on to benefit the diagnosis and management of dementia?

The main causes of dementia are Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease and cerebrovascular disease (e.g. stroke), although there is overlap between the dementias. Dementia with Lewy bodies is a common but less well understood form of dementia, associated with the abnormal accumulation of a protein called alpha-synuclein. People with DLB have problems with memory and thinking, mood, behaviour and movement.

Diagnosing DLB is challenging and delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis is common. Our lab has established the Lewy Body Study – an observational longitudinal clinical and biomarker study which aims to better understand DLB and identify clinically useful biomarkers to support the diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring.

This is the first Australian study of its kind, and has helped provide a framework for the much-needed therapeutic trials. Our laboratory has an interdisciplinary clinical approach to dementia research.

Our main aims are to improve the diagnosis of dementia through the use of blood-based biomarkers, establishing dementia cohorts to address important risk factors and facilitate clinical trials of novel therapeutic agents, developing investigator-led clinical trials, supporting the development and access to dementia research for regional and rural Australians, addressing caregiver health needs and importantly, supporting the next generation of clinician researchers in dementia, through education and mentorship.

What are the challenges dementia research faces? What barriers do you have to overcome as a researcher with this particular focus?

We need greater collaboration, between specialist fields and a multidisciplinary approach, to diagnosis, treatment and research. Geriatric medicine has not historically been a research-intensive specialty, so we need strong mentors to inspire people to pursue research opportunities in this field.

A lack of gender diversity in this research discipline is also an issue and is one of the aspects that attracted me to WEHI, which is highly regarded for its emphasis on diversity and inclusion. I am keen to see diversity issues in research change but it is slow. I supervise six PhD students who are also clinicians and four of them are women, which is a really positive sign.

There needs to be greater support for women in research. WEHI is dedicated to supporting women in science and promotes women and men in equal numbers within the organisation, which is so important, not just in this field but in all aspects of science.

Where do you hope to see dementia diagnosis and management in the next 10 years?

One of the things we are working on at the moment is blood-based biomarkers for the clinical diagnosis of dementia. This is essentially a blood test for dementia. Dementia is associated with different pathological proteins and we have been able to measure these proteins in spinal fluid.

With current technological advances we are now able to measure some of these proteins in the blood. We have technology at WEHI that is helping us develop that blood test. This is especially important for people living in rural communities where there is less access to specialist care and advanced brain scanning infrastructure. Having a blood test diagnostic tool simplifies the process and provides improved diagnostic accuracy and earlier diagnosis.

We need comprehensive assessment and management available to all Australians – including regional, rural and remote, Indigenous Australians and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Early diagnosis is really important because it means people living with dementia and their families can identify changes and have the education and support in place early on, it also enables easier to access vital support services.

An early and accurate diagnosis will also allow us to develop better treatments. It seems that because there aren’t effective treatments, that an accurate diagnosis is somehow less important. But nobody has had that approach towards advancing treatments for cancer. We need to approach treating dementia in the same way. We also need to make patients with dementia in more diverse communities a greater priority.

I am optimistic about future treatments and improvements in dementia. Attitudes are shifting towards a greater focus and commitment to this area of research.

Is the disease under-examined when it comes to how it affects women due to research gender bias in the past?

I’m not aware of this as a factor. Women have been involved in much of the dementia research as participants. The concern really is that more research is needed.

What are some of the major misconceptions about Dementia and how it affects women?

Memory loss can be considered a normal part of ageing, although this isn’t specific to women. Women are frequently involved in the informal care of family members with dementia, often parents. This can also come at a time in their lives when they also have caring responsibilities for children and careers.

At what age roughly should women begin to pay attention to their memory and mood changes? How do women tell the difference between mood changes affected by other stresses, and neurological causes?

Memory problems can occur throughout life, and are not necessarily due to dementia. Busyness, stress and fatigue can contribute to memory lapses, mainly because it’s more difficult to concentrate. Memory loss due to a neurodegenerative condition will progressively worsen over time and need support to manage daily activities such as managing finances early on in the condition and in later stages, managing domestic tasks.

Do mind-games actually help? Can you suggest any?

Some studies have found that cognitive training or “mind-games” can improve some aspects of memory or thinking but so far, no studies have shown that these prevent dementia. More research is needed to further understand potential benefits. I suggest a game or activity you enjoy doing. Social engagement is important so it’s great if the game is something that can be shared with others.