The nausea. The pain. The cramping.

It was endometriosis: a condition she was diagnosed with at age 24, that had got progressively worse with every passing year.

The Christmas flare up spurred her to purchase a ticket to a patient-centred endometriosis conference that was being run that May by the advocacy group, EndoActive.

“One crisp day…in a University of Sydney auditorium, I learnt for the first time that all the things wrong with me – the period pain, leg pain, back pain, hip pain, shooting pains up my rectum and vagina, bloating, nausea, diarrhoea, stomach upsets, dizziness and the oh-so-debilitating fatigue – were common symptoms of endometriosis,” Jackson writes. “I cried and I cried and I cried. For most of my life I’d doubted myself, feeling second-rate, weak and flaky, only to realise … I wasn’t.”

Jackson, The Guardian’s opinion editor, approached the then editor of Guardian Australia, Emily Wilson, and said she wanted to write about the condition that an estimated 176 million women worldwide have. A disease that impacts as many people as diabetes and yet receives just 5% of the funding.

Wilson was shocked enough by these figures to consult The Guardian’s Editor in Chief, Katharine Viner, and what resulted very quickly was a global investigation into ‘the invisible disease’.

On the 10th of September when The Guardian asked endo sufferers to share their own experiences with the condition, within 24 hours, 600 responses had been sent.

Two and a bit weeks later when The Guardian launched its global investigation, a million people clicked.

The feature that Gabrielle Jackson wrote about her experience has been shared more than 40,000 times. It began:

“I feel sad that this is the hardest story I’ve ever written and that I’m embarrassed that people will read it and know the intimate details of my life. But I’m also hopeful that a conversation has begun.”

Several years on she still receives emails and messages from readers about it.

“So many of them tell me it feels like I found their words, because their story is frighteningly similar to mine. We’re linked only by our experiences with an insidious disease, one that’s common yet ignored, and with a worldwide patriarchal healthcare system.”

The overwhelming response was the catalyst for Gabrielle thinking more widely about women’s pain and how it is viewed and treated, not just by the medical profession, but by wider society.

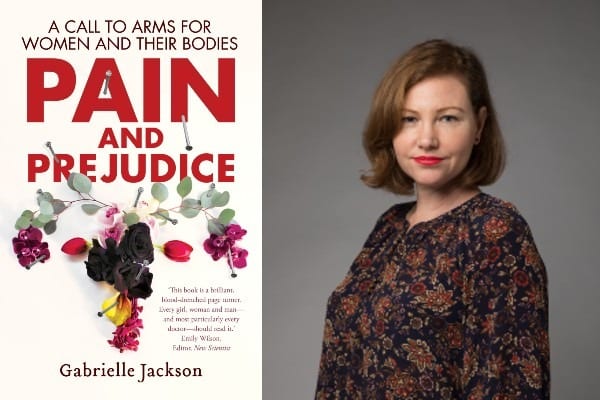

The result is Pain and Prejudice, part memoir, part polemic on the state of women’s health in today’s world, published this week by Allen and Unwin.

Caroline De Costa, a professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at James Cook University, describes it as ‘a major contribution to feminist writing of the 21st century’.

“Jackson takes her own story of endometriosis, a neglected and mistreated condition, and builds around it a careful analysis of how women’s pain has been ignored or belittled over centuries by a sexist medical profession,” De Costa says. “This is highly recommended reading for all women, their partners and families – and their doctors.”

In Pain and Prejudice she very forensically and frankly examines how women, historically and through to present day, are being ‘underserved’ by a health system that ought to keep them healthy and informed.

Her research led her to realise that being ignored was the norm for almost any illness affecting women in particular – not just those impacting the female reproductive system. Heart disease, auto-immune conditions and chronic pain are three examples of conditions Jackson says that women get, or that react differently in women than men, that aren’t researched or understood or treated adequately.

And too many women suffer because of it. The problem is not merely a few sexist doctors: it’s systemic.

With humour, insight and considerable research, Jackson makes a compelling case for why and how this structural problem can be begin to be unpicked.