As the rate of Covid-19 infections across the world continue to climb, there is growing evidence that the virus discriminates by sex, with men more likely to test positive, and to suffer more serious illness and higher mortality rates than women. While the reason remains unclear, one hypothesis is that men’s immune system response is less active than women’s.

When it comes to our collective response to this pandemic, though, the situation is reversed. In every country, the consequences of measures taken to address the growing health and economic crises are likely to be felt more by women, on a number of fronts.

Women make up 70% of the global health and social care workforce. In Australia, the figure is significantly higher: 78.2% of workers in our health care and social assistance industry are women.

These are the people on the frontline of our response to the biggest health crisis in living memory. The administration of tests, the care of those already ill enough to require care in hospital, the provision of medical advice over inundated telephone hotlines – all are services overwhelmingly provided by nurses, of whom, in Australia, 87.9% are women.

Other care work is similarly dominated by female workers, none of whom have the luxury of working from home. 96% of childcare workers are women, as are 87% of direct care workers in residential aged care. These are the women caring for the children of other essential workers, and looking after our elderly loved ones while they are isolated from family and friends.

70% of disability support workers are women too, going every day into the homes of people living with co-morbidities that make them exceptionally vulnerable to the effects of Covid-19 should they contract it.

While schools remain open, and even when we move to online education, the majority of the teachers providing lessons to our kids will be women: 81.9% in primary schools, and 60.8% of secondary schools.

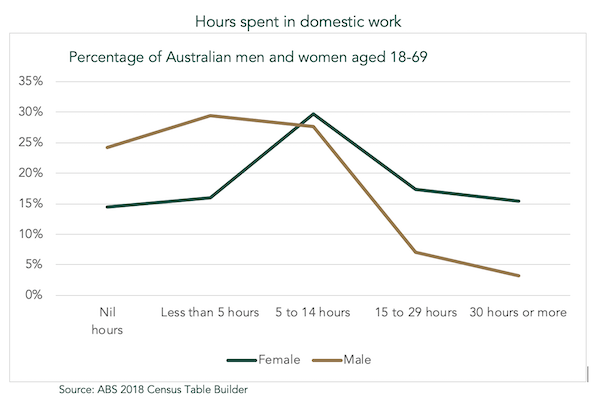

Given that Australian women spend 80.8% more time on unpaid household work each day than men, that imbalance will almost certainly be reflected in the division of labour for home schooling, with women more likely to interrupt their own paid work to help their kids.

Australia has always had a high rate of occupational gender segregation by OECD standards, and WGEA data conclusively shows that people working in industries with a predominantly female workforce have lower salaries than those working in male-dominated industries.

As we grapple with this unprecedented pandemic and the shut-down of our economy, it has become clear that the workers essential to the operation of society are not highly paid executives in financial services and investment banking; they are the people stacking our supermarket shelves, nursing our sick, caring for our elders, cleaning our hospitals and educating our kids.

They make up what is known as “the foundational economy”, and are amongst the lowest paid workers in society, because much of what they do – providing food, cleaning, teaching and caring – is regarded as women’s work, and we don’t value it.

These jobs are also notoriously insecure: over recent decades, we have deregulated employment in the foundational economy so that a significant proportion of its workforce is employed on part-time and casual contracts. They live pay-cheque to pay-cheque, with little capacity to save.

At least their jobs are relatively secure in this crisis, with a relatively small proportion likely to have been laid off due to the economic shut down compared to workers in other sectors. But consider this: many of those that have been stood down will get a higher rate of take home pay from the government’s Job Keeper payment of $1500 per fortnight than will their colleagues who remain at work.

What’s more, far too many low-paid women in insecure jobs won’t receive the payment at all, under the proposed eligibility criteria. As speedy modelling from Rebecca Cassels and Alan Duncan at the Bank West Curtin Economics Centre showed last week, two of the industries hardest hit by our economic lock down – Accommodation and Food Services, and Retail Trade – have by far the highest number of casual employees with less than 12 months’ service for their current employer, most of whom are women. More than 200,000 female workers in those sectors alone will miss out on the wage subsidy due to its design.

There are other aspects of the government’s response that disproportionately disadvantage women. As well as excluding people in receipt of the disability support payment from the recent supplement to the Job Seeker payment, those in receipt of the carer allowance were also left out. Almost twice as many women (540,000) as men (230,000) are the primary carers for friends or family members with disabilities or physical and mental illness, including end-of-life care, in Australia.

Another concern is the move to allow early access to superannuation. Largely due to the fact that they work in underpaid jobs, and take on the lion’s share of unpaid work and care, women in Australia retire with significantly lower superannuation balances than do men.

If they choose to withdraw the maximum $20,000 from their super, women will suffer a significantly greater impact than will men: based on current average balances, women’s super will be reduced by roughly 50% more than men’s, resulting in even greater inequalities in retirement nest eggs due to the multiplier effect of the loss of compound interest.

The good news is that the government appears to be listening to expert advice as it works its way through its response to this pandemic. Early reports that the wage subsidy was to be offered only to full-time workers were not borne out, after the Opposition and economic commentators raised alarm at the exclusion of women who make up the vast majority of those employed part-time.

As a slimmed-down Parliament returns to Canberra this week to consider the legislation needed to implement the Job Seeker payment, we can only hope that it applies a gender lens to its analysis of the Government’s package. Our representatives must, as far as possible, eliminate anything that will exacerbate the already disproportionate economic and social impact this pandemic, and our response to it, will have on Australian women.