Girls are far more likely to be developmentally ready to start school, and remain ahead on many measures, particularly literacy, throughout the early and middle years. However by senior secondary these gaps have narrowed, and by adulthood young men are faring much better on economic measures.

In short, after a slow start, boys overtake girls and race ahead.

This was the surprising finding from a new report Educational opportunity in Australia 2020: Who succeeds and who misses out. The landmark report tracked the young Australians’ educational outcomes from school entry to young adulthood. It’s the first major study to look at the broad goals for education set out in the Alice Springs Declaration, including confidence, creativity, and community engagement – as well as academic performance and progress.

It found that Australian boys and girls are experiencing a very different journey through the education system, and that, while gender is no barrier to equality of opportunity and achievement within the education system, we should be asking some very serious questions about what happens after that.

Girls start off ahead

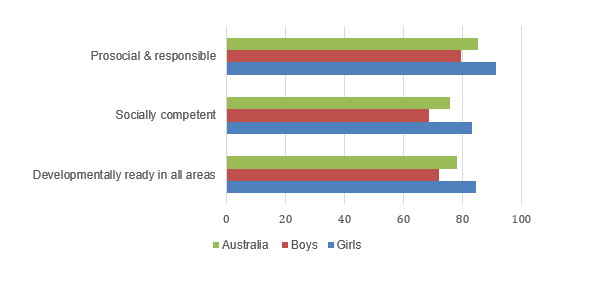

Girls make a strong and confident start. At school entry, and through most of school, girls demonstrate higher levels of prosocial skills, creativity, literacy, and interest in engaging with the world around them – between 6 and 20 percentage points higher than boys.

Girls are half as likely to be developmentally vulnerable on entry to school.

Percentage of girls and boys developmentally on track at school entry

Confidence levels shift in adolescence

However during the middle years we see a concerning trend – girls’ levels of confidence and self-belief are lower compared with earlier childhood, and compared with their male peers. This trend has been widely researched, with similar gaps evident in many countries.

In secondary school, 78 per cent of males are very confident compared with 73 per cent of females, and 72 per cent of males demonstrate strong self-belief compared with 62 per cent of females. These gaps persist into adulthood.

Boys catch up fast

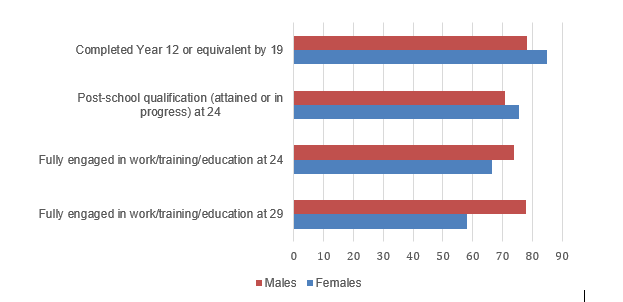

While girls and women are more likely to complete school (85 per cent compared to 79 per cent of boys) and attain a university degree (39 per cent compared with 27 per cent of men) we are still not seeing girls’ success in the classroom translate into equality of opportunity in adult life.

At the last milestones examined in the study – ages 24 and 29 – young women are less likely than young men to be fully engaged in work, education or training. 53 per cent of men are engaged in full time work or study at age 24, compared to 43 per cent of women. Over one third of women are not engaged in work, education or training at all.

Male and females in post-school education, training and work

This quite dramatic decline in participation and engagement among women in their 20s, even university graduates, can partly be explained by the fact that females are much more likely to report caring responsibilities for children and other family members, even at age 24.

Yes, women are more likely primary carers, but there’s more going on here – with the evidence showing girls and young women unable to ‘capitalise’ on their education in the same way as young men.

The gender pay gap kicks in early on, with female university graduates paid less than their male counterparts. This trend is only further entrenched in the childbearing years, with lifelong consequences for women’s pay, superannuation and economic independence.

The report’s findings show Australia’s education system is, on the whole, serving girls and women well, but that broader policies settings are failing to promote equality for men and women after they leave the school gates.

Girls start off on a stronger footing than boys, but are not supported to translate their educational successes into economic opportunity and success in later life. While economic success is only one measure, and may not be the most important, it does matter.

Education should be about providing every individual with the skills and capabilities to pursue a life that they choose, and policies around work and family should support fairness and choice, regardless of gender.

However the stark differences in workforce participation and pay between men and women in Australia, despite women’s higher levels of educational achievement, show we still have much more work to do.

Kate Noble and Sarah Pilcher are Policy Fellows at the Mitchell Institute for Education and Health Policy at Victoria University.